Seeing Olmec colossal heads in photographs is one thing. But when you stand in front of one, it’s not just their size that strikes you. It’s also their presence, one that exudes both calmness and power.

The best place to experience that presence is the Museo de Antropología de Xalapa (MAX) in Xalapa, Veracruz.

MAX is considered the second-most important anthropology museum in Mexico (the first being the Museo Nacional de Antropología in Mexico City). The first museum in Xalapa to exhibit pre-Hispanic artifacts to the public, MAX opened in 1943. A larger museum was opened on the current site in 1960, only to be torn down in 1985 to make way for an even larger museum.

The third iteration of the museum, designed by U.S. architect Raymond Gómez, opened on October 29, 1986. All of the 2,500 artifacts on display are from pre-Hispanic Veracruz civilizations: Olmec, Remojadas, Tajín, Zapotal and Huasteca.

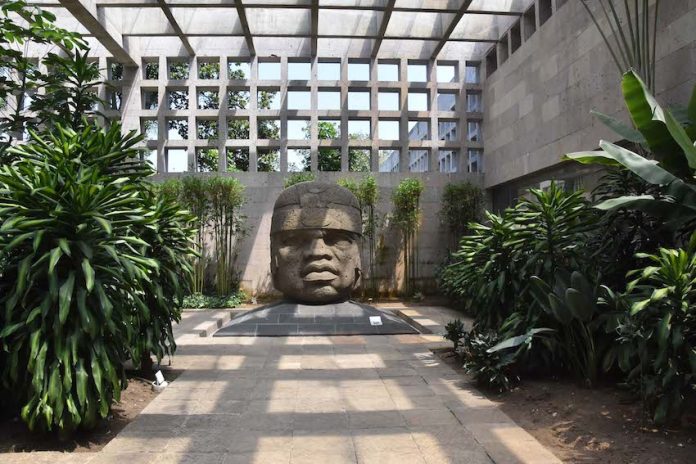

The building has one long gallery that connects to nine smaller galleries on one side. Three of these are covered patios where prehispanic figures and altars sit among trees and plants. Beautifully landscaped grounds surround the museum.

Colossal Head Number 8 greets visitors at the entrance to the museum (the numbers signify the order in which the heads were found). Standing just over 7 feet tall, it has the same characteristics found on all of the heads: a flattened nose, thick lips and fleshy cheeks. All also have a helmet, which may have afforded protection in pelota, the ancient Mesoamerican ball game, or in battle.

Believed to be the portraits of rulers, Olmec heads were carved from basalt boulders transported from the Sierra de los Tuxtlas mountains. To date, seventeen heads have been found and seven can be viewed at the MAX. The heads range in height from 1.17 to 3.4 meters (3.8 to 11.2 feet) and weigh between 6 and 40 tons. Although it’s not known with certainty when the heads were carved, information at the museum dates them to between 1,200 and 900 B.C.

Although all of the heads share common characteristics, each one is unique. For example, Number 3, located with two others in a side room, is thought to be the portrait of a woman. To her right is Number 9, who sports a Mona Lisa-like smile, and to her left is Number 4, who looks a little grim.

Although the heads may be the most impressive of the museum’s pieces, there are many others that are also fascinating.

Near the museum’s entrance are exhibits and information about the important role women played in pre-Hispanic cultures in Veracruz.

With 2,500 artifacts in the museum, it’s difficult to choose favorites. But, in addition to the colossal heads, here are a few others that I found particularly interesting.

A sculpture of Tlazolteotl, the fertility goddess and one of the most important gods of all pre-Hispanic cultures, is at the entrance to the main gallery. She sits, cross-legged, gazing serenely while Colossal Head number 5 watches from behind her.

El Señor de Las Limas is a beautiful figure carved from green serpentine with an interesting backstory. It was found by two children in 1965 in Las Limas, Veracruz (hence the name) who were looking for a rock to break open coyoles, the small, hard fruits of a palm tree.

Luckily, the children found a rock sticking out of the ground and used it to break open the fruits. Fortunately, no damage was done. They brought the rock to their home where people realized it was an ancient sculpture. Originally named La Virgen de las Limas, the townspeople placed it in the local church. It was later taken to the MAX where, in 1970, it was stolen and eventually recovered in a San Antonio, Texas motel.

The figure is 55 cm (22 inches) high and depicts an adult, possibly a priest, sitting cross-legged and holding a limp baby in his arms. While it could depict a sleeping baby, it could also represent one that was sacrificed.

Another favorite is the small figure of the Dios del Fuego (Fire God) who appears happy as he rubs his hands together and drops offerings into a brazier. Nearby are Xipe Tótec, the god of agriculture and human sacrifice, whose body is covered in human skin, and Tlaloc, the rain god who looks oddly like a WWI pilot.

One of the more disturbing exhibits is the gallery of deformed skulls, a practice undertaken to show kinship and status, as well as for aesthetic reasons. The deformations were typically performed on infants; the exhibit displays ceramic sculptures depicting children strapped on beds to prevent movement while bands or boards were placed to deform their skulls.

Figure on taking a couple of hours to tour the museum. After that, take advantage of what Xalapa has to offer.

The historic center has lots of restaurants and cafés to check out. A little advice: if you drive to Xalapa, park your car before heading to the city’s center and take taxis, which are reasonably priced – the traffic is brutal. Also, Señor Google kept sending us to the commercial center when we asked the app for directions to the historic center. Either ask someone for directions, or type in Parque Juárez, which is a good starting point within the historic center.

There, you’ll find people selling food, skaters on skateboarders and live music. The park has a huge statue of Quetzalcóatl with an extended tongue that children like to slide down.

For a more tranquil experience, there’s the beautiful Parque de los Tecajetes, which is a short ride from the city’s center. It has gardens and pools filled with fish and turtles and is a nice break from the hustle and bustle of the city.

Lastly, do not leave Xalapa without trying a hot glass of lechero. A glass of coffee is brought to your table and then a server, in a sort of perfomance art piece, pours in hot milk. Although I prefer my coffee black, I found lechero delicious.

MAX is open Tuesday through Sunday, 9 a.m.to 5 p.m. and costs 60 pesos to enter. The second floor has temporary exhibits.

Joseph Sorrentino, a writer, photographer and author of the book San Gregorio Atlapulco: Cosmvisiones and of Stinky Island Tales: Some Stories from an Italian-American Childhood, is a regular contributor to Mexico News Daily. More examples of his photographs and links to other articles may be found at www.sorrentinophotography.com He currently lives in Chipilo, Puebla.