Lena Bartula, “La Huipilista,” an American textile artist living in San Miguel de Allende whose work is rooted in social consciousness and environmental awareness, is currently inviting anyone concerned about the plight of victims of the war in Gaza to participate in her latest project, YO TE VEO (I SEE YOU). Using crowd-sourced squares of fabric, each with an open eye stitched onto it by a volunteer, Bartula will craft a huge huipil, a traditional tunic worn by Indigenous women in Mexico and Central America.

YO TE VEO: Finding a way to bear witness and contribute

“YO TE VEO,” Bartula explained, “is a call to witness those who otherwise may be unseen or forgotten. I created this collaborative textile art project when I felt despair and hopelessness creep in over the tragic situation unfolding now in Gaza.

Bartula invites volunteers to join her at her studio and other locations in San Miguel de Allende and also encourages volunteers around the world to form their own stitching groups and mail the squares they create to her for inclusion in the project. Interested readers may contact her at [email protected] to request either “starter kits” of fabric squares precut to the correct dimensions or to learn the specifications to cut their own fabrics. Stitching groups have already formed in Mexico City, Mazatlán, Michoacán, and as far afield as Seattle and Ontario.

All YO TE VEO squares must be received by March 15, 2024, to be sewn into the oversize huipil, which will be displayed at the Museo de Arte Popular in the center of Mexico City from May 29 to Aug. 4 as part of a retrospective solo show entitled Hilo Corriendo or A Running Thread.

The role of the huipil

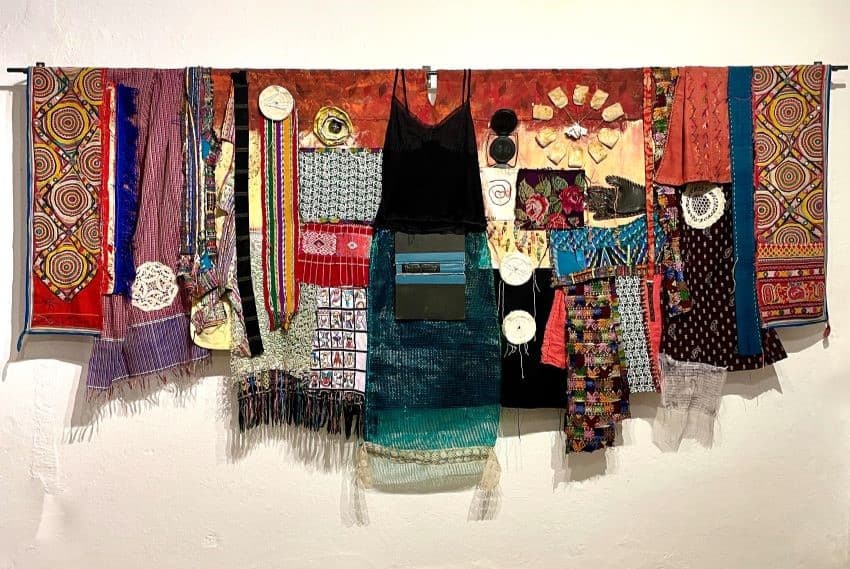

A traditional huipil is embroidered with geometric figures that reveal aspects of the wearer’s life, but only to the initiated — the Spanish conquerors could not read it. They didn’t know the story underneath the story.

Bartula explained why she chose the huipil as the underlying form for her artwork. “A huipil is known to be a messenger, a garment that carries information from the weaver to the wearer and to the world at large. With this project, YO TE VEO, our message to those persons suffering from genocide, political upheaval, displacement due to violence, climate change, et cetera, is that we see them. We witness what is happening. When feeling helpless to change their situations, we often despair and grow weary. Through this project, we commit in solidarity and humanity, to stand as witnesses, by embroidering an open eye that conveys the message I SEE YOU. YO TE VEO. Further, we ask for donations to be sent to an NGO to assist with addressing the medical emergencies that we are seeing now in Palestine.”

Maité Jiménez, a textile designer who hosts sewing circles at Radio Nopal in San Miguel de Allende, was also motivated by this collaborative art project’s emphasis on acknowledging displacement and migration and giving disheartened observers a way to contribute.

Bartula strongly prefers that people work in groups, with friends or family members, because she believes that there is a healing quality in people sitting in community and together creating something beautiful for a cause.

Participants in the YO TE VEO project are encouraged to make a donation to an NGO that is providing emergency medical services and food in Gaza. For more information about the organization or to make a donation, visit https://matwcheckout.org/.

From painter to textile artist, from Santa Fe to San Miguel de Allende

In 1993, Barula first traveled to Mexico and Central America with a group of American radical feminist nuns who were working in war-torn Central American countries. The nuns created an organization called GATE: Global Awareness Through Experience. “They left their Dominican convent and said, ‘We’re going to do the work.’ They were such revolutionaries, and I was awed by them and their work. I also fell in love with Mexico during that time,” she said.

Two years later, while still living in Santa Fe, New Mexico, Bartula was invited to the Feria Internacional del Libro de Guadalajara (Guadalajara International Book Fair) to present art commemorating the Royal Road that led from Mexico City to Santa Fe during colonial times. “I was a radical back then, so I painted a huge image of Indigenous people revolting against the priests and setting the churches on fire.”

Inspired by these experiences, Bartula moved to Mexico from Santa Fe in 2004, living for several years in Mineral de Pozos, Guanajuato, before settling in San Miguel de Allende.

Her transition from painting to textile art has a practical backstory. After suffering the expense of shipping her paintings to France for an exhibition, when she received her next international invitation, to exhibit her work in Milan, Bartula consciously chose to work with fabric, so that her work could be folded into a suitcase. For years, she had been collecting traditional huipiles for their beauty and originality but hadn’t thought of making her own textile art until then.

Her first garment was inspired by Santa Lucía, who, according to legend, dug out her own eyes to keep herself from being married off to a man she didn’t love. For Bartula, this led to fifteen years of work to tell the stories of the many powerful women who need to be talked about, those who had to stand up for their rights but whom history has often forgotten, such as Mexico’s own Sor Juana and Hypatia, the noted philosopher of Alexandria who was killed by “mad monks” before they burned the Library of Alexandria. Bartula’s works about women are chronicled in a 2018 book entitled “Whispers in the Thread/Susurros en el Hilo: Celebrating 15 years of contemporary art huipils by Lena Bartula.”

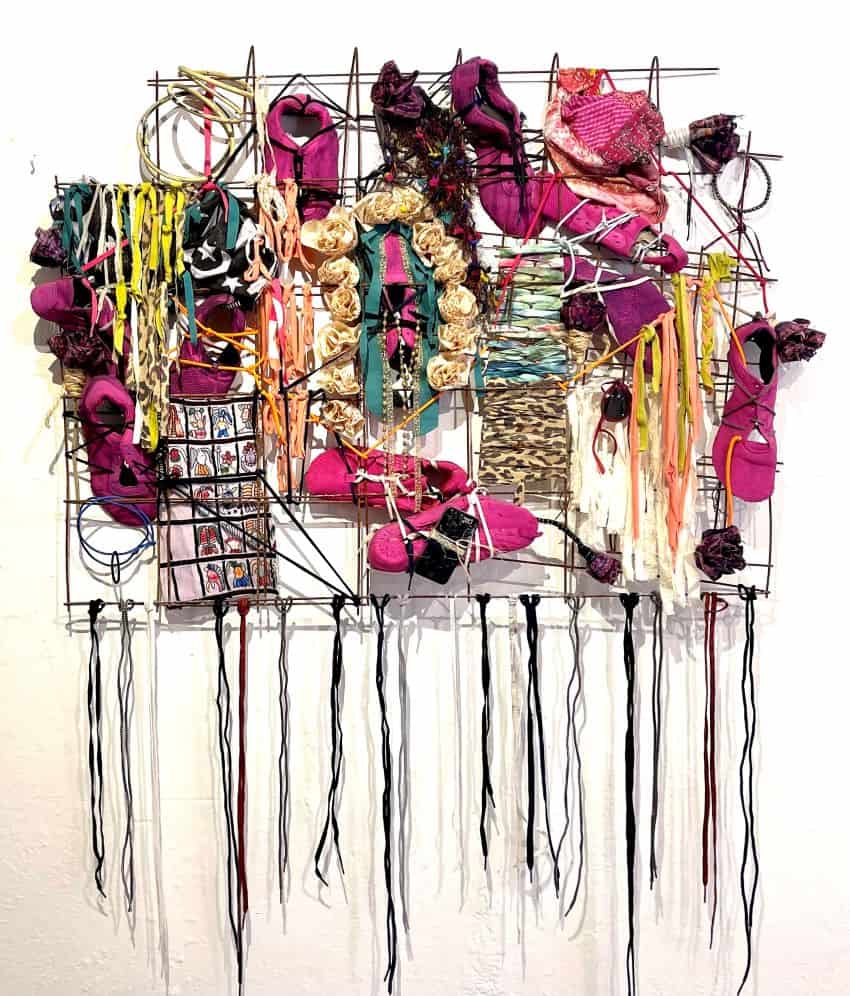

Since 2018, pandemic isolation and migration have been dominant themes in Bartula’s work.

She also notes that 99% of the materials she uses are recycled or found objects. “I am both a recycling artist who loves textiles and a textile artist who loves to recycle. There’s no separation for me between my art and the world, or the world and my heart. When I see something happening in the world, it comes into me and then it comes out again as art. That way it doesn’t have to stay inside me, in my psyche. I work with it, and then it moves out into a bigger world so that other people can either feel it — or not. That is their choice, but at least I’ve done the work and offered it to the world.”

To learn more about Lena Bartula’s art and to participate in the YO TE VEO project, visit www.lenabartula.com or contact her at [email protected].

Based in San Miguel de Allende, Ann Marie Jackson is a writer and NGO leader who previously worked for the U.S. Department of State. Her award-winning novel “The Broken Hummingbird,” which is set in San Miguel de Allende, came out in October 2023. Ann Marie can be reached through her website, annmariejacksonauthor.com.