Hidden in plain sight are many things that tell the story of Mexico’s multicultural history.

While we tend to think of the country as having a monolithic mestizo heritage (a blend of Indigenous and Spanish), there are important additions left behind by groups of immigrants that have shaped the country’s culture, art and its cuisine.

Middle Eastern immigrants brought tacos árabes to Puebla which would go on to become Mexico’s most ubiquitous taco — tacos al pastor. Lebanese immigrants brought the kibbe to the Yucatan, now a popular roadside street food, and in Mexico City, one Japanese immigrant invented what would become one of Mexico’s most beloved snacks — cacahuates japoneses or Japanese peanuts.

Yashigei Nakatani: From Japan to Mexico

Japan and Mexico have diplomatic ties stretching back to the 1800s when both countries signed a Treaty of Friendship, Trade and Navigation. By the time World War II rolled around, there was already a nascent Japanese population in Mexico — in Manzanillo, many were fishermen, in Guadalajara Japanese workers came to work on the railroad, and of course, many arrived in Mexico City, the country’s capital which held the most economic opportunities for recent immigrants.

When Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, the United States pressured the Mexican government to move Japanese immigrants away from the ports and the borders, and many in the community were deported on the alleged suspicion that they were spies.

That was the case with Heijiro Kato, the factory owner and boss of Yoshigei Nakatani Moriguchi, a young immigrant working in Kato’s button factory in Mexico City.

Nakatani had been in Mexico since 1932. He arrived and rented a room in the capital from his future mother-in-law, in the downtown neighborhood of La Merced, determined to make something of himself in his new adoptive city.

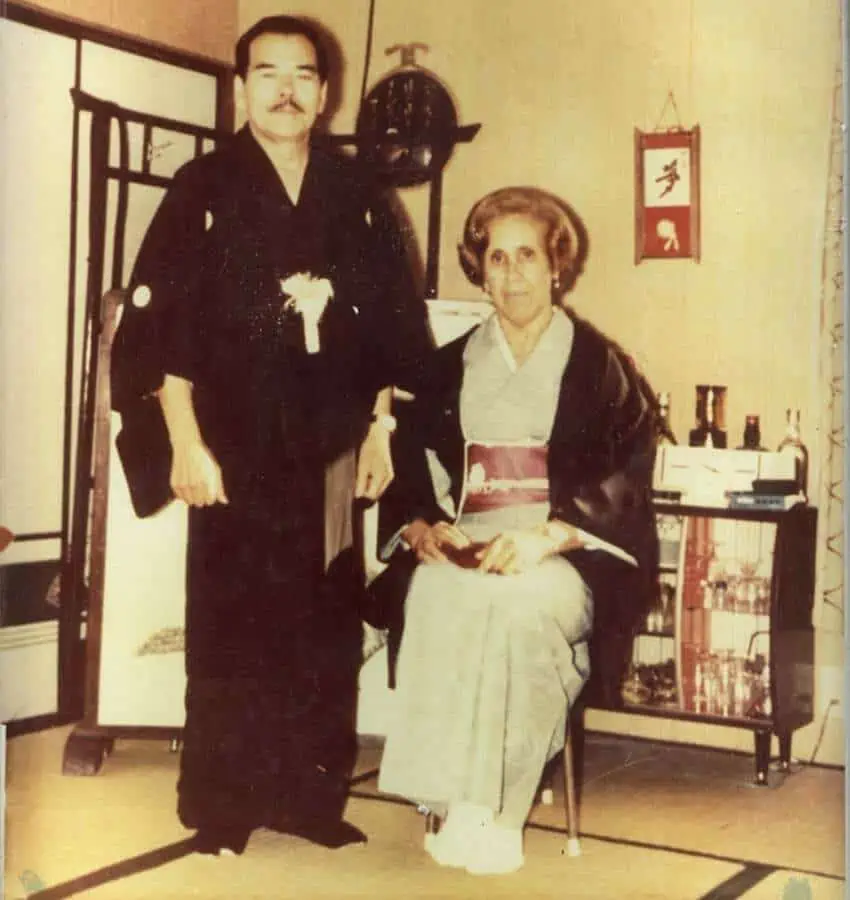

Nakatani soon met and fell in love with his landlady’s daughter Emma Ávila, who spied him singing on the rooftop of the building they shared and began to teach him Spanish. By 1941, they had five children and when Nakatani lost his job at the factory, he needed to find a way to make an income fast.

A new variation on a Japanese confection

Growing up in his hometown of Sumotoshi, Nakatani had learned how to make traditional Japanese sweets and candies. He figured he would try his hand at selling confections, so he and his wife started making muéganos, a Mexican candy made from flour, nuts, and coated in honey. Selling them out of their house on Carretones Street in the Merced, the candies were a hit, so they decided to expand and try to replicate a popular snack from Nakatani’s childhood — peanuts covered in a coating made from rice flour with soy sauce, and a touch of sugar.

Rice flour wasn’t available, so he replaced it with wheat flour, but the resulting snack was as good as the original — slow-toasted until perfectly golden brown, with slight salty spice and a hint of sweetness.

Everyone in the family eventually formed part of the business — his children helped to design the logo, pack the peanuts into their tiny cellophane bags, and run the machinery that they would eventually acquire to keep up with demand. In the neighborhood they were known as “the Japanese guy’s” peanuts and so Nakatani decided to name his business Cacahuate Nipón in the 1950s.

A family business and legacy

Business boomed and by 1970, Cacahuate Nipón officially incorporated and moved out of their space in the Merced neighborhood to produce on a larger scale. Unfortunately, the recipe for Japanese peanuts was never patented and during the 1980s, Cacahuate Nipon faced competition from big industrial corporations that were also making the snack, placing them in some of the country’s biggest convenience store chains.

The family overcame this challenge by expanding production to other popular sweets, like chamoy candies. They were extremely successful and were bought by Totis (part of La Costeña) in 2017, after which they started a new company called Dulces Komiru.

More recently, continuing the culinary legacy of his family, chef Eno Nakatani, grandson of Yashigei Nakatani, opened Fideo Gordo, a Japanese-Mexican noodle shop in Mexico City’s fashionable Colonia Roma.

Here he makes fusion dishes like ramen in birria broth and pork chicharrón topped with shrimp ceviche. Fideo Gordo is just one of the newest examples of Mexico’s great gastronomic melting pot, inspired by the many cultures that have expanded the country’s palate to the delight of locals and visitors alike.

Lydia Carey is a freelance writer and translator based out of Mexico City. She has been published widely both online and in print, writing about Mexico for over a decade. She lives a double life as a local tour guide and is the author of Mexico City Streets: La Roma. Follow her urban adventures on Instagram and see more of her work at www.mexicocitystreets.com.

This article is part of Mexico News Daily’s “Japan in Focus” series. Read the other articles from the series here.