The drums of the sogochum workshop on the Korean Cultural Center’s patio compete with the whir of a metal floor fan to drown out Vivian Oh in the kitchen classroom. As she giggles at her own jokes, we all strain forward to hear the instructions for making spicy Korean chicken soup with noodles, or dak-kalguksu.

Oh has a high-pitched lilting Spanish that after 20-plus years in Mexico is still heavily laced with the sounds of her native Korean.

Oh came to Mexico in 2001 at the behest of her best friend, who was already living here in the city. It was her first trip out of Korea, and she came with little knowledge of the place that would soon become her new home.

She started giving cooking classes at Centro Cultural Coreano when it opened 13 years ago.

Oh joined the estimated 9,000 to 11,000 Koreans currently living in Mexico City – a tiny fraction of the immigrants that reside in the capital. This immigrant group has often had out-sized visibility due in part to the wave of Korean culture, or hallyu, of the 1990s and 2000s, when cultural exports like K-pop and Korean soap operas became world-famous.

The Mexico City area known as “Little Seoul” is part of the Juárez neighborhood’s Zona Rosa. The Korean Cultural Center, however, was built in the Polanco neighborhood, where you will find far more Jewish restaurants than Korean ones. Oh explains why.

Koreans, she says, have been moving to Polanco in the last several years as big companies like Samsung and LG have brought their employees to Mexico.

Mexico’s first wave of Korean immigrants

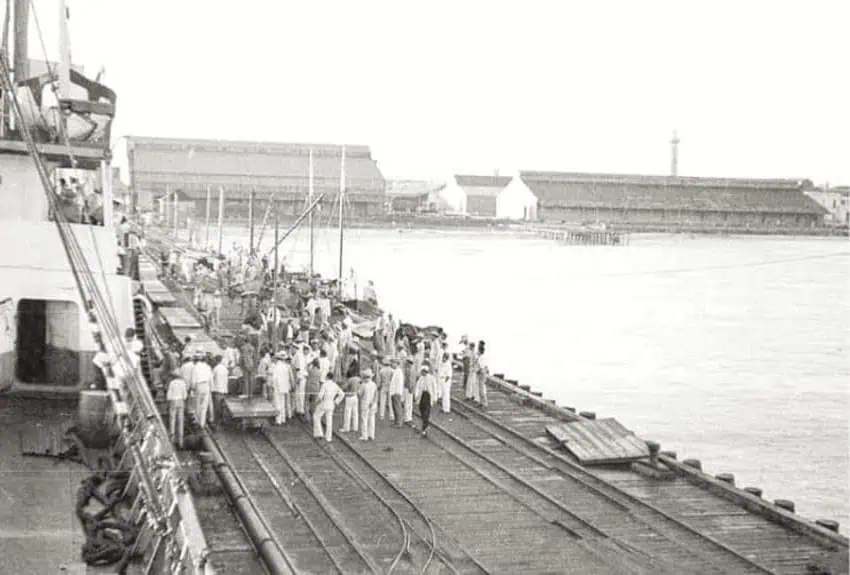

The first Koreans to arrive in Mexico landed in the Yucatán in 1905, fleeing the mounting dominance of the Japanese empire, which would annex their country only five years later, leaving them stateless.

Deceived by the empty promises of labor recruiters, the first transplants to Mexico worked as semi-slaves in the region’s henequen farms, in debt to the plantations’ company stores upon arrival and suffering under terrible working conditions.

Many of those first 1,000 or so Korean immigrants intermarried with the Maya of the region, adopting regional customs so fiercely that when several were interviewed years later, they admitted to feeling more Korean-Yucatec than Mexican.

The establishment of diplomatic relations between Mexico and South Korea in 1962 increased the flow of Koreans to the country, but not enough to build much of a community. Restrictive immigration policies in the United States often resulted in Mexico being a fallback choice for Koreans and Chinese citizens.

According to Sergio Gallardo García, who researched the Korean diaspora in Mexico City, the largest wave of Korean immigrants to the city was between the 1980s and 2005, when South Korea’s economy was flourishing and immigrants came with money to invest or start small businesses.

This was when Korean churches, associations, and cultural centers started to really develop. Oh remembers arriving at this time and living in the south of the city near the UNAM campus, where a community of Korean students had formed. During these years, Koreans who had previously immigrated to Argentina or Brazil moved to Mexico in an attempt to escape economic and political instability in South America.

It was in the years of the K-wave and Mexico City’s Korea Town, or Little Seoul, as it’s sometimes called, really started to develop. Even so, when Oh arrived in 2001, she remembers often being confused for Chinese.

“When I arrived, everyone in the street just called me china, but now people say, ‘You’re Korean right? I have a lot of Korean friends.’ In 20 years, it’s completely changed.”

The most recent wave of Korean immigration, Gallardo García says, has been made up of students and workers coming to Mexico to learn Spanish and work in the Latin American headquarters of Korean companies. South Korea, he adds, has made moving abroad easier with institutions dedicated to informing immigrants of the news back home, helping them to send remittances to family in South Korea and helping them mitigate issues in their new countries.

These days, you can find Korean restaurants and grocery stores tucked into many of the Zona Rosa’s side streets, providing a taste of home for those who have made the crossing.

In Korea, Oh’s mother taught her to pull noodles when she was 10 years old, and she would gather minari from the edges of the rice field where her parents worked. When she arrived in Mexico, many traditional ingredients were still impossible to find.

“I really want to teach the authentic flavor of Korea,” says Oh, “even though, at times, it can still be difficult to find Korean ingredients. Once people have tasted the original flavors of Korea, then they can adjust the recipes to their own tastes.”

The Korean peninsula’s most well-known culinary exports to the world are probably kimchi (there are hundreds of varieties of this spicy, pickled cabbage dish) and Korean barbecue – a mere fraction of the culture’s culinary lexicon.

Fermented snacks and salsas — often spiced with gochugaru, miso, garlic, ginger or Korean chilli paste — are usually served as part of side dishes or banchan at every meal. Spicy noodle soups, Korean fried chicken, whole fried fish, grilled meats and steamed veggies are almost always served alongside a bowl of rice, with chopsticks and a long spoon for eating.

Where to find authentic Korean food in CDMX

For a traditional Korean feast, order the bossäm platter a day in advance from Angela and her husband, who opened Seoul at 177 Londres Street in the Zona Rosa a few years back. A cornucopia of tiny dishes (banchan) holding things like sweet peanuts sprinkled with sesame seeds, a rolled omelet with onions and peppers, and a creamy cucumber-and-onion salad will be laid out in front of you.

Dabs of this or that fermented salsa, or slices of raw serrano chile are combined with a spoonful of egg souffle, grilled strips of beef or a spicy tofu-and-clam soup. This spread is easily enough for three or four people and will open up your mind to the range of Korean flavors.

Na De Fo is a standout among the city’s Korean BBQ restaurants, managed by the Lee family since 2007 and now part of a Korean restaurant group with various spaces around town.

On the westernmost end of Liverpool Street, each table at Na De Fo has an opening at its center with a grill at table level. Diners can order from a bevy of meats — bacon, beef, pork, fish, tongue — that they cook themselves on the grill in front of them. All are accompanied by grilled greens, spicy kimchi, mung beans and a selection of different vinegary and spicy sauces. The punchy kimchi chigae soup should not be missed.

View this post on Instagram

This video by a Mexican Instagrammer features dishes available at Na De Fo, a Korean BBQ restaurant that has been in Mexico City for decades.

For something less traditional with a bit of Mexican fusion thrown in, try Jowong, a chic, modern bistro in Condesa. The menu is designed to incorporate Mexican ingredients into contemporary versions of Korean dishes. Their mussels are heavenly, swimming in a tangy tomato sauce, and the tender fried eggplant has a deep charred flavor that’s hard not to love. The sweet, mustardy pork belly is a nice contrast to the quick-pickled smashed cucumbers served on their own as a side.

The nice thing about Jowong’s upscale setting is that you can get a Goldboy cocktail (mezcal, yuzu and ginger), a kimchi Gibson (gin, vermouth, and kimchi juice), or other delicious beverage concoctions to accompany your meal.

I also highly recommend the cooking demonstrations at the Centro Cultural Coreano. Although there’s no hands-on work for attendees, Oh gives the Korean names for ingredients and shows you which products she uses from the Korean grocery store. She even offers movie recommendations and will always invite you to stay after for the Korean music workshop.

You get to taste whatever delicious thing she happens to be cooking that day, but you have to bring your own bowl.

Lydia Carey is a freelance writer and translator based out of Mexico City. She has been published widely both online and in print, writing about Mexico for over a decade. She lives a double life as a local tour guide and is the author of “Mexico City Streets: La Roma.” Follow her urban adventures on Instagram and see more of her work at mexicocitystreets.com.