You probably don’t associate apple farming with Mexico, but it is regionally important, especially in areas where few other commercial crops grow.

The main reason is that apples grow well in the high, cold and very rugged areas of Mexico, as they need the cold that would kill many other fruits.

Apple cultivation started only 20 years after the conquest, but it was prohibited to the indigenous, most likely because its primary purpose was to make hard cider. This kept the fruit from becoming a widespread part of the colonial diet, but missionaries later did bring the tree north as they introduced agriculture to nomadic peoples.

Today, apple trees can be found everywhere that they can grow in Mexico, but they account for only 3% of Mexico’s commercial fruit production. Most are grown in small orchards or in backyards, so they have not reached their full potential as a commercial crop.

Most of Mexico’s 15 federally defined apple-growing regions are in the Sierra Madre Occidental, stretching from Chihuahua to parts of Oaxaca and Chiapas. The top producers are Chihuahua, Puebla, Durango and Coahuila, but Chihuahua is far in the lead, producing anywhere from 70% to over 90% of Mexico’s apples (depending on which source you believe).

Chihuahua also leads in the production of table-ready fruit, which commands a higher price. This is due in part to low precipitation, which mars the apples’ skins, but also due to a history that includes American and Canadian immigrants such as the Mennonites, who were used to growing apples in their colder homelands and developed markets and introduced new technologies.

Most of Chihuahua’s apples are grown in and around the municipality of Cuauhtémoc. This area not only has over 2,500 growers, but also many greenhouses, packing plants and apple processing plants.

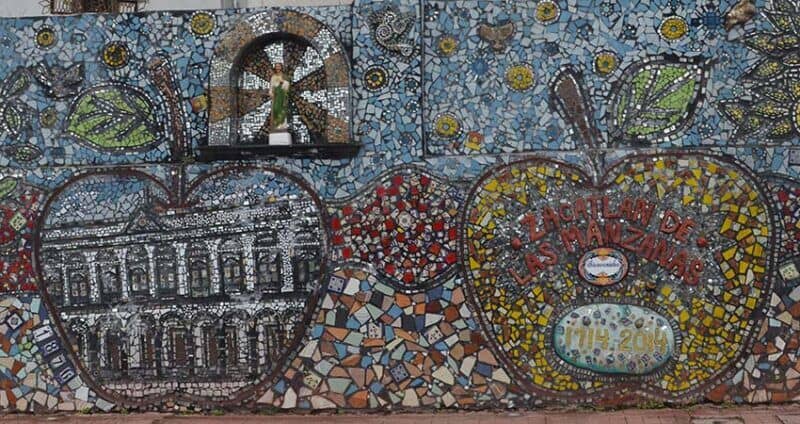

Puebla has the oldest apple industry in Mexico, focused mostly on the municipalities of Huejotzingo and Zacatlán. Most fruit is for processing into juice, vinegar, tea and, very traditionally, a sweet, bubbly alcoholic cider.

History plays a role here, but so does Puebla’s far rainier climate, which eliminates much of the need for irrigation, but does also potentially contribute to damage to the apples’ skins and pest infestations that can ruin whole crops.

Much of Durango shares the same climate advantages that Chihuahua has, but a lack of private and public investment hinders the state’s farmers. Here, apple production is concentrated in and around Canatlán, near the city of Durango proper.

Although increasing in other places, Durango’s production has dropped, says Alfonso García Soto of the Sistema Productor de Manzana, which represents about 100 Durango farmers. The main issue is the abandonment of lands suitable for apple production because of the state’s inefficient irrigation system, along with lack of access to needed technology.

That does not mean that those states that don’t have the production levels of the “Big 4” aren’t looking to compete better. Institutions such as the Autonomous University of Querétaro have done genetic and other research to improve quantity and quality. It is important to these states because apples often grow in some of their poorest municipalities.

Mexico meets 77% of the domestic demand for apples, most of which is consumed fresh. The average Mexican consumes only just over eight kilos per year, compared to Poland (67.5 kilos), Turkey (35.4 kilos), Iran (34.7 kilos) and China (31.4 kilos).

One probable reason Mexico’s consumption is so relatively low is that it does not have a tradition of cooking the fruit that these countries do. Apples are also consumed as juices or other beverages, which utilize about 30% of annual production. After juice boxes, the most important apple drink is a mildly alcoholic carbonated cider, traditional nationwide for Christmas and New Year’s.

Mexico ranks between 20th and 22nd in apple production globally, but it is not a major apple exporter. Its production overall has grown only marginally since 2000. To date, its commercial production and consumption is only regional, but it is still on the federal government’s radar.

According to the National Agricultural Plan 2017–2030, authorities hope to increase production by 40% by 2030. The reason for the optimism is that there is much room to grow, if (like in Durango) the right resources and management are available.

One relatively simple technology to implement is the use of special nets that cover trees during certain seasons to protect them, their flowers and young fruit from hail. In the deserts, they also provide shade during the hottest months.

But these nets are extremely expensive, costing hundreds of thousands of pesos per hectare, out of the reach of most small farmers. And so these farmers have “damaged” fruit, which only industrial processors are interested in and for which they pay a very small amount.

Another area with room to grow is in agricultural tourism. There are few apple farms that offer tours, even those near population centers. Harvest time is between late July and mid-October, with its peak in September.

Although the “pick-your-own” concept is known, especially in northern Mexico, which is closer to the border with the United States, where it is an institution in some states, it has not been implemented as far as I can tell.

Apple towns worth visiting include Cuauhtémoc, Chihuahua; Canatlán, Durango; and Zacatlán, Puebla. Apples mainly attract visitors to the towns proper, rather than to the farms, where restaurants and specialty shops offer apples and apple preparations, especially during harvest season. They generally appeal to local and regional tourists and make for great alternative weekend trips.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 18 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.