With Mexico’s rich art history, why isn’t it a major draw for foreign art students?

Actually, it was. During the colonial period, Mexico was at the forefront of the fine arts in the Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking New World, with the region’s first major art school, the Academy of San Carlos.

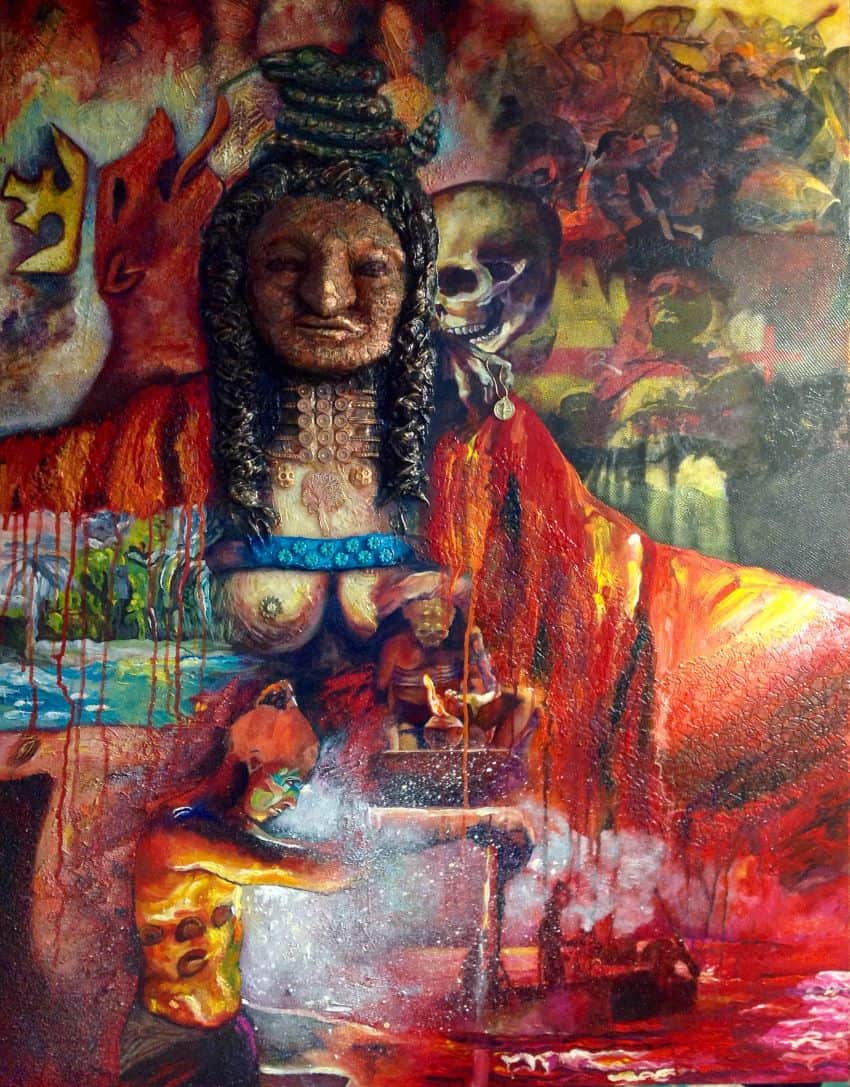

For the modern era, the muralism movement of Diego Rivera and company not only continued Mexico’s “big brother” status in Latin America, it rivaled France globally as a destination for budding artists.

The two periods of Mexico’s art prominence resulted in two major national art schools. The aforementioned San Carlos was integrated into the National Autonomous University (UNAM), itself highly prestigious. After several reorganizations, it is now the Faculty of Art and Design (FAD), headquartered in the south of the city, but it keeps the old San Carlos building for its graduate program.

The other is the La Esmeralda National School of Painting, Sculpture and Engraving. This school was established by the muralist generation in Mexico City and is part of the National Institute of Fine Arts.

Both schools still attract international students, but nothing like the decades after the Mexican Revolution. At that time, the interests of the art world and the Mexican government coincided to create a juggernaut of creativity and, yes, propaganda that is still featured in Mexico’s tourism and cultural campaigns. But avant-garde artists moved on from nationalism by the 1950s, making the government less motivated to promote anything but the old murals, even today.

In the decades after the Revolution, the government did sponsor quite a number of foreign students to San Carlos and La Esmeralda. These efforts produced greats such as Guatemalan Rina Lazo and Chilean Osvaldo Barra Cunningham, who had a great impact on murals produced both in Mexico and their home countries.

Today, however, neither school has well-organized, sustained programs specifically targeting foreign art students.

One attempt to do so happened at FAD in the 2000s. The school signed a number of exchange agreements, including one with the Altos de Chavón Design School, a small technical art institute in the Dominican Republic. This two-year school does not offer a bachelor’s degree, necessary for many teaching jobs, so the arrangement was to have Chavón students transfer, study two years in Mexico and get a FAD/UNAM diploma.

The year 2006 brought six students to Mexico City, with about 20 more the following year. It was not a moneymaker for UNAM as such students paid the nearly free in-country tuition. The goal was to broaden FAD’s reputation outside Mexico. Unfortunately, the university administration changed the following year, and FAD abruptly stopped accepting Chavón students, despite the formal agreement. This is not that unusual as new administrations come in with different priorities (see what is happening with the new Mexico City airport). UNAM agreed to allow Dominican students already registered to finish their degrees, but the program was over.

Former UNAM art program director Luz del Carmen Vilchis says that one highly satisfactory aspect of working with foreigners is seeing the impact they have after returning to their home countries.

But not all graduates go back. Mexico and its culture have much to offer foreign artists. In the case of those from Caribbean countries, the sheer size of the cultural scene here is awe-inspiring. At least three of the 20-plus Chavón students have made Mexico their home, developing careers as artists and teachers.

Carmen América Rodríguez Sánchez came to UNAM, finding visa and language issues easier in Mexico than in the United States. That does not mean that moving to Mexico City was easy. From a small town on a small tropical island, she found herself in one of the world’s biggest metropolises. Although eminently grateful for what it has offered her as an artist, she finds the city cold and gray, which has muted her color schemes.

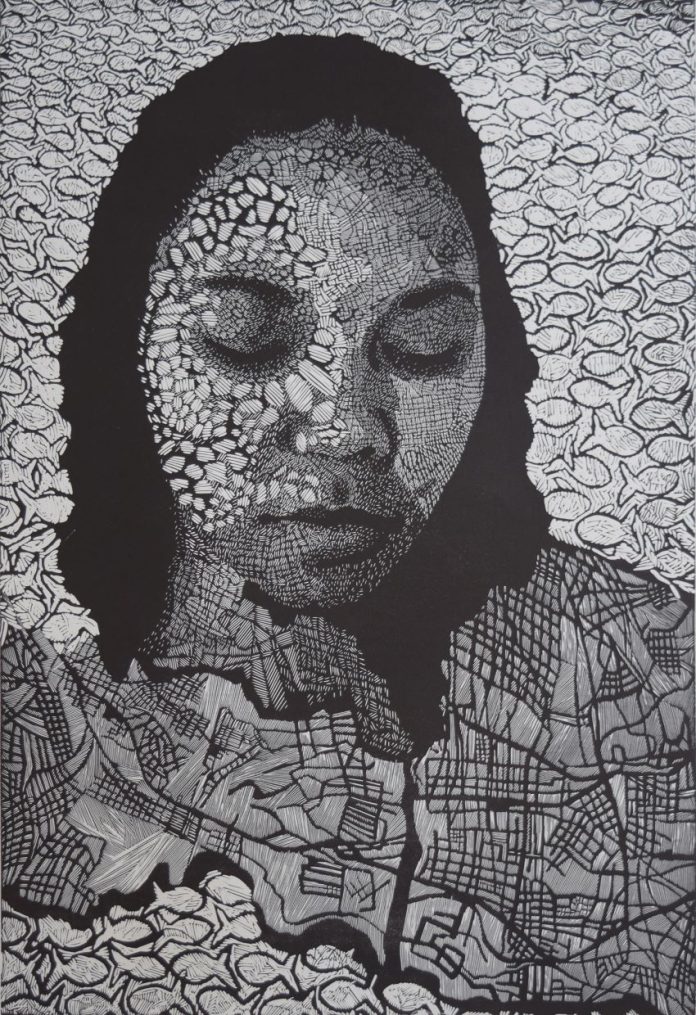

She still lives near where she studied, in part because the area is the closest in feel to a small town in the chaotic capital. Rodríguez’s work is often in mixed media, using many of the painting, graphics, embroidery, mosaic and ceramic skills she learned in both Mexico and her home country.

Niurka Guzmán Otañez was also part of the first group, but instead of staying on in Mexico City after graduation, she eventually wound up in Cozumel because of a teaching job.

“My work as a printmaker has been enriched in Mexico,” she said. “Here I learned different metal engraving techniques, printing and manipulating ink viscosity. I feel that living in Mexico has helped me communicate and structure my ideas with its artistic and cultural riches. They have been a grand inspiration.”

Another transplant to Cozumel was actually an exchange student twice over. Farah Jane Cadet is from Haiti. She was accepted as an international student at Chavón and then began the process to study at FAD.

Unfortunately, she had not formally registered as a student when the exchange program was terminated. She was allowed to continue taking classes as an observer but could not earn a degree. After ending her studies, she also made her way south to Cozumel, where she now works as an art teacher, able to do so in English as well as Spanish (and, of course, her native French Creole).

You might think that the former Chavón students living in Quintana Roo would feel more at home than those who live in Mexico City. But while the climate is similar and it is closer to their island homes, there are only a few similarities. Guzmán says that it is still a very distinct world because of the lack here of a history of African peoples.

The women’s ethnic backgrounds, especially their African heritage, makes them stand out in Mexico. While they acknowledge that they can be the object of curiosity, none have felt mistreated here — quite the opposite: all indicated that they and their work have been accepted and respected, sometimes even preferred, since they offer a new perspective.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 17 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture. She publishes a blog called Creative Hands of Mexico and her first book, Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta, was published last year. Her culture blog appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.