“We’ve won empty space and made paths for walking,” says Jorge Cravioto as he eyes the ever-encroaching forest that surrounds him.

It’s a delicate balance: protecting the fast-growing bamboo, the year-round crickets and the nesting ground of dozens of tropical birds while building a coffee plantation and hotel for visitors.

His project, Finca Brasil, is tucked into the mountains of southeastern Chiapas, right along the Guatemalan border, and while the coffee business here is ancient tradition, this plantation has a futuristic vision for the region’s coffee industry.

Finca Brasil has become a standout example of local coffee farming because of Cravioto and his wife Magda’s commitment to agroforestry, a system of production that harmoniously incorporates cash crops — in their case, coffee — into the surrounding natural landscape. As part of that production system, they grow other flora that they can sell for a profit – things like fruit trees or hardwood trees to be sold for lumber. The system has a lot of benefits, everything from increasing biodiversity to reducing the risk of erosion, and it stands in opposition to conventional commercial coffee production, where land is cleared so coffee bushes can be planted in direct sunlight.

“The main product of this region is coffee,” Cravioto says, “but the price of coffee is suddenly high and then super low, and it’s never enough for the families to live on,” says Carvioto. “The model of Finca Brasil is to grow coffee but also to grow other things.”

However, he quickly adds, “If all I wanted from the coffee was money, I would plant in the direct sun like everyone else.”

Instead, he insists, he and Magda see Finca Brasil as a long-term project that will allow them to make their own small contribution to the future of the planet.

“We need to agree that climate change is real,” he says. “If we don’t protect these spaces, what will we leave for future generations?”

The Craviotos are just one pair of producers in a 20-member coffee collective in Sierra Mariscal, a seven-municipality coffee-growing region on Chiapas’ southernmost border.

Working together, the collective members are developing and promoting a gourmet coffee route here, one that will bring outsiders in to taste the beans, experience the land, and hopefully buy directly from producers.

Finca Brasil, because of its facilities – their coffee-growing land encircles a rustic eight-room hotel and colorful gardens – has been chosen as one of the bases for exploring this new coffee route.

But if Finca Brasil demonstrates the first step in excellent coffee – growing and harvesting sustainably – Cafe Nueva Maravilla, run by Elías Morales and his wife Wendy, showcases the next.

“My father was a coffee producer, and from the time I was very young, I was involved in production,” says Morales, a quiet man with an easy smile. He opened Nueva Maravilla with his wife a year ago in order to spotlight the area’s highest quality coffee from a wide range of altitudes. He started toasting his own beans 10 years ago and now works with his neighbors to toast theirs.

“[The] habit we had before — me as well — was that you grow the coffee and you sell all of it that’s good and you’re left with the bad. We don’t do that now; we are drinking good coffee and trying to teach people about drinking good coffee.”

Instead of selling all their best coffee to intermediaries, they are now saving some of it, not only for their own consumption but also to sell in their cafe and to offer to visitors that find their way to this 600-person community in the Chiapas mountains. The hope is to develop direct contact with buyers, which they hope will translate into higher prices for the producers – who would make pennies on the dollar using the intermediaries.

“Someone can come and say, ‘I want this coffee from 1,200 meters … I want this one from 1,400 …’,” Morales says. “People say that high-altitude coffees are very acidic, but we can always do a combination of the beans: one that’s 1,600 meters with another that’s 1,000 meters. So in the end, it’s not too acidic, nor is it too mellow.”

He’s been learning this precision alchemy as the collective has worked to produce select coffee – using the term to describe a kind of coffee where everything from the planting of the seeds to the pouring of the finished product has been cared for.

“Now I can grab a handful of beans and just by smelling them determine how the final cup will be,” Morales says proudly.

Like Finca Brasil, he is also using agroforestry techniques and has noticed the difference.

“When the hurricanes passed through, people who had been cutting down their trees suffered a lot of damage [to their crop], but we were fine because the trees helped to keep the roots in the ground,” he says.

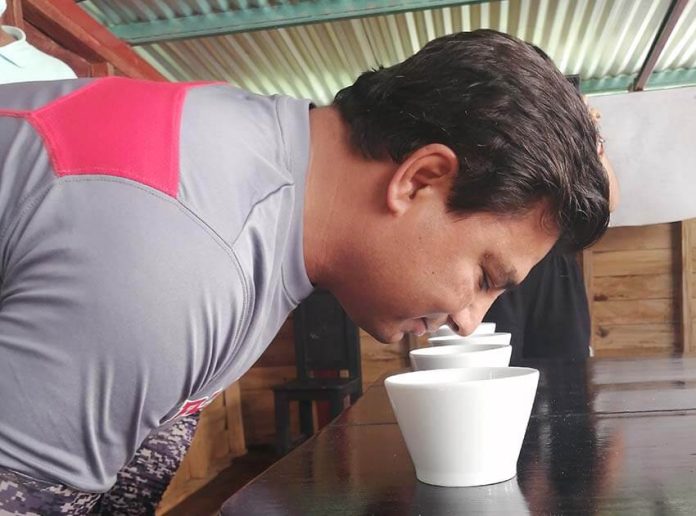

Samuel Mendoza, another collective member, runs through a list of characteristics that can be used to describe a specific brew. Mendoza has become an official coffee taster, a skill as complex as being a sommelier or tequilier.

He walks a group of visitors through an extensive but down-to-earth tasting at Cafe Nueva Maravilla, showing them how to gently scoop the grinds that settle on the surface of the coffee, how to slurp from their spoons to disperse its taste throughout and what changes they will notice as the coffee cools from its original 198 F – the officially agreed upon correct temperature for coffee tasting.

“The specialty coffee sector is very rigid in terms of price and sustainability,” says Mendoza, “We want to create added value in order to increase the prices we can get for our coffee. We want to build more cafes like this one, develop the region’s coffee route, and make our coffee more visible.”

Remote and isolated, the coffee communities of Sierra Mariscal are not easy destinations for the average traveler. Mendoza and his business partner have been integral to bringing visitors to experience the coffee route via their local tour company, Travis Tours. They are also working with local authorities to improve roads and encourage investment in tourism infrastructure.

While there is still a long way to go, the collective members have already implemented important new techniques into their coffee production and are learning to value in a new way the product that their families have grown for generations.

“Some say that the best coffee is high-altitude coffee, but the best coffee is one that is cared for from the very beginning to the very end,” says Cravioto.

Lydia Carey is a regular contributor to Mexico News Daily.