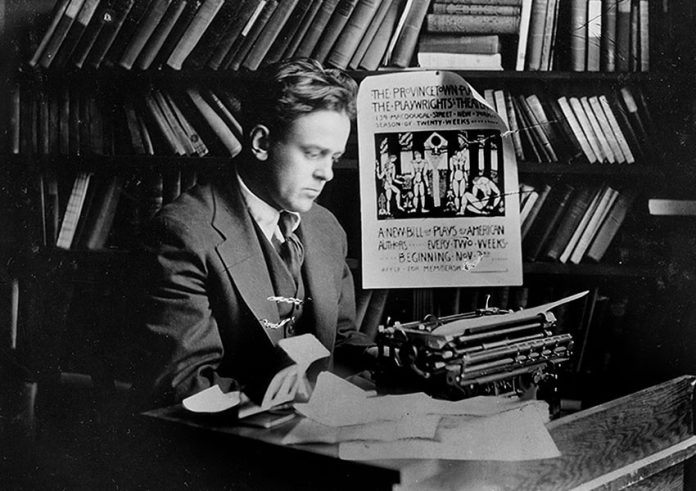

In 1913, leftist American journalist and poet John Reed spent four months traveling with Pancho Villa’s army, sending regular dispatches to Metropolitan Magazine in New York City, which were collected and published the following year as “Insurgent Mexico,” still available as a free ebook from Project Gutenberg.

Reed’s preconceived notions about Mexicans changed radically during his time as a war correspondent here, and he later described his days in Mexico as the “most satisfactory period” in his life.

It’s easy to find books describing the Mexican Revolution in terms of battles and dates, but Reed excels at showing us the aspirations, frustrations and quirks of the generals, soldiers and “peons” (as he likes to call them) caught up in the conflict.

An example is Reed’s conversation with Torribio Ortega, one of the first generals to revolt against Porfirio Díaz, who had become a de facto dictator after decades in power.

Says Reed: “At dawn next morning, General Ortega came to the [train] car for breakfast — a lean, dark Mexican who is called ‘The Honorable’ and ‘The Most Brave’ by the soldiers. He is by far the most simple-hearted and disinterested soldier in Mexico.”

“He never kills his prisoners,” Reed continues. “He has refused to take a cent from the Revolution beyond his meager salary. Villa respects and trusts him perhaps beyond all his generals. Ortega was a poor man, a cowboy. He sat there, with his elbows on the table, forgetting his breakfast.”

“‘You in the United States,’ said Ortega, smiling, his eyes flashing, ‘do not know what we have seen, we Mexicans! We have looked on at the robbing of our people, the simple, poor people, for 35 years, eh? We have seen the rurales [country police] and the soldiers of Porfirio Díaz shoot down our brothers and our fathers, and justice denied to them. We have seen our little fields taken away from us and all of us sold into slavery, eh? We have longed for our homes and for schools to teach us, and they have laughed at us. All we have ever wanted was to be let alone to live and to work and make our country great, and we are tired — tired and sick of being cheated…’”

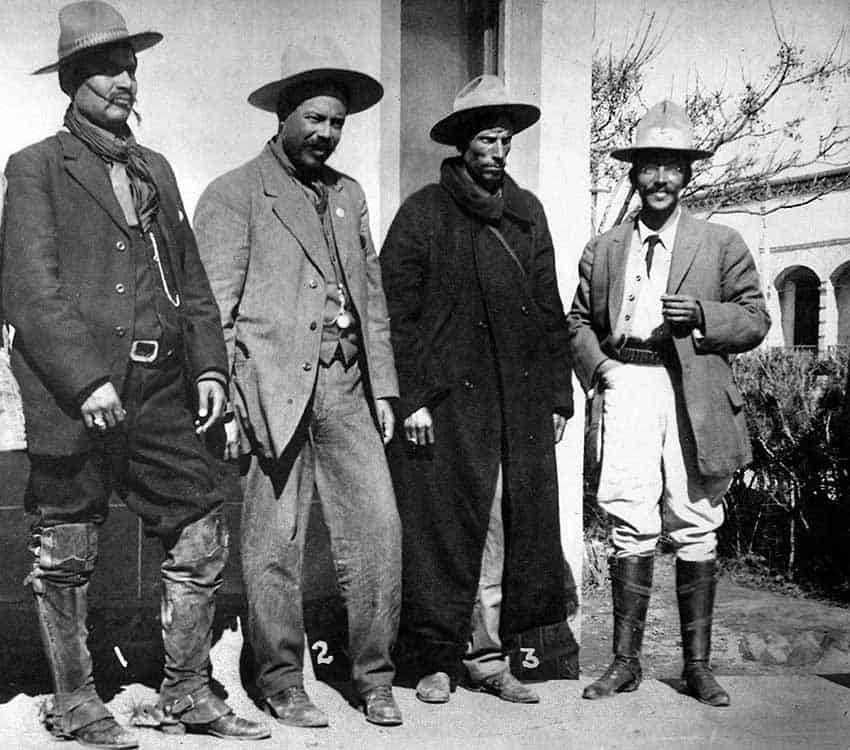

Reed introduces Francisco “Pancho” Villa — born José Doroteo Arango Arámbula and a key figure in the revolution — like this:

“Villa lived in El Paso, Texas, and it was from there that he set out, in April, 1913, to conquer Mexico with four companions, three led horses, two pounds of sugar and coffee and a pound of salt.”

Reed greatly admired Villa’s original and imaginative approach to warfare, which he was forced to invent for himself because he never had an opportunity to learn accepted military strategy.

“His method of fighting,” says Reed, “is astonishingly like Napoleon’s. Secrecy, quickness of movement, the adaptation of his plans to the character of the country and of his soldiers — the value of intimate relations with the rank and file, and of building up a tradition among the enemy that his army is invincible and that he himself bears a charmed life — these are his characteristics.

“And where the fighting is fiercest — when a ragged mob of fierce brown men with hand bombs and rifles rush the bullet-swept streets of an ambushed town — Villa is among them, like any common soldier.”

Reed gives us an example of Villa’s humor in this exchange with locals in Durango watching the passing of his army from atop a little mound.

“‘Oyez!’ said Villa. ‘Have any troops passed through here lately?’

‘Si, señor!” answered several men at once. ‘Some of Don Carlo Argumedo’s gente [people] went by yesterday pretty fast.’

‘Hum,’ Villa meditated. ‘Have you seen that bandit Pancho Villa around here?’

‘No, señor!’ they chorused.

‘Well, he’s the fellow I’m looking for. If I catch that diablo, it will go hard with him!’

‘We wish you all success!’ cried the pacificos [noncombatants] politely.

‘You never saw him, did you?’

‘No, God forbid!’ they said fervently.

‘Well!’ grinned Villa, ‘in the future when people ask if you know him, you will have to admit the shameful fact! I am Pancho Villa!’ And with that, he spurred away, and all the army followed.…”

Finally, Reed gives us a few insights on the futility of war from “an old peon, stooped with age and dressed in rags, crouched in the low shrub, gathering mesquite twigs.”

Reed, anxious to see action after crossing a dusty plain outside Torreón, Coahuila — where a fierce battle was raging — asked the old man how he could get close to where the fighting was taking place.

The aged campesino (farmer) straightened up and stared at his inquisitor. “‘If you had been here as long as I have,’ said he, ‘you wouldn’t care about seeing the fighting.

‘Carramba! I have seen them take Torreón seven times in three years. Sometimes they attack from Gómez Palacio and sometimes from the mountains. But it is always the same — war. There is something interesting in it for the young, but for us old people, we are tired of war.’ He paused and stared out over the plain. ‘Do you see this dry ditch? Well, if you will get down in it and follow along, it will lead you into the town.’ And then, as an afterthought, he added incuriously, ‘What party do you belong to?’

‘The Constitutionalists.’

‘So, first it was the maderistas [followers of revolutionary leader Francisco I. Madero], and then the orozquistas [followers of leader Pascual Orozco] and now the — what did you call them? I am very old, and I have not long to live; but this war — it seems to me that all it accomplishes is to let us go hungry. Go with God, señores.’”

“Insurgent Mexico” offers us a chance to look into the very souls of those caught up in the Mexican Revolution. This remarkable book is well worth reading.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, since 1985. His most recent book is Outdoors in Western Mexico, Volume Three. More of his writing can be found on his blog.