Although it weighs less than an ounce, the lesser long-nosed bat has a big impact in Mexico: it pollinates the agave plant that humans use to make tequila, earning it the nickname of the “tequila bat.”

For decades, UNAM ecologist Rodrigo Medellín has been working to preserve this tiny but vital species. Now his efforts are being recognized in an episode of the PBS series Nature.

“The Bat Man of Mexico” is narrated by celebrated British natural historian Sir David Attenborough and produced by the British Broadcasting Corporation. It follows Medellín’s determined campaign to save the lesser long-nosed bat, in part by raising awareness of its importance to the tequila industry.

“The lesser long-nosed bat and the agave have an intimate connection,” Medellín said in a phone interview. “One depends on the other for their survival and sexual reproduction.”

As he explains, an agave plant reproduces just once in its life, via a flower created by sugar that has accumulated in the plant. Bats feed on nectar from the flower. In doing so, they help agave plants exchange genes with each other.

However, all of this was jeopardized toward the end of the 20th century by declining bat populations. In the 1990s, the bat was placed on the endangered species list in both Mexico and the United States and was at risk of going extinct.

“Since then,” Medellín said, “I started working on a recovery plan — what needed to happen for the species to recover.”

Over the past two decades, in the 13 largest-known colonies of the bats in Mexico, “all of the roosts have become stable or are growing,” Medellín said. “There’s evidence of growing new colonies we had not known about.”

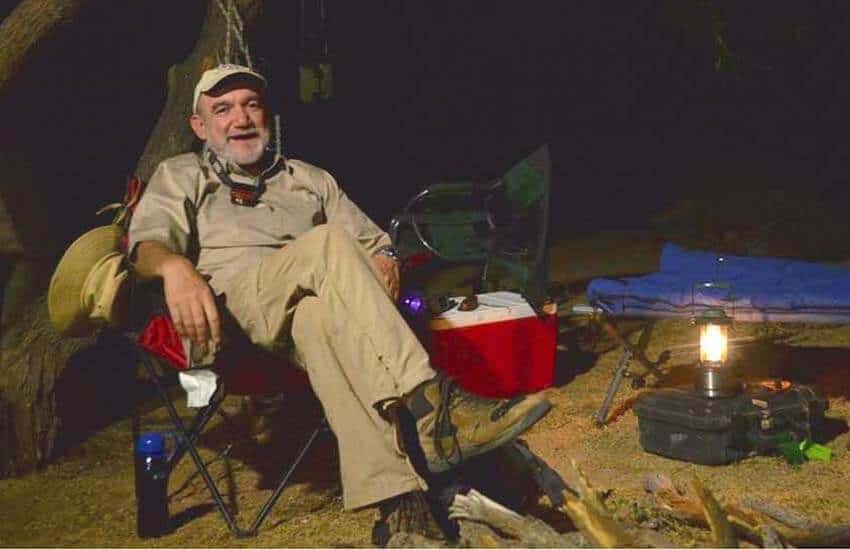

In the documentary, he tracks the bats’ numbers by following their three-million-strong migration across Mexico, from the caves of Calakmul in the south to the Sonoran Desert to the north. Along the way, he braves a hurricane, snakes and swarming cockroaches. The documentary shows the bats on the move — in what it calls “a living tornado” that is meant to discourage predators — as well as groundbreaking footage of a live birth.

“These bats are the sweetest bats you could possibly think of,” Medellín said. However, he noted, “Like any wild animal that you hunt, a lizard or a snake or a rat … they will try to bite you if they want to defend [themselves] or perceive you as a predator.”

A fascination with bats dates back to his childhood. As shown in the documentary, the young Medellín began an up-close study of a species known for its bite, the vampire bat. Since becoming a scientist, he’s done conservation work with many other animals, including jaguars, bears and bighorn sheep.

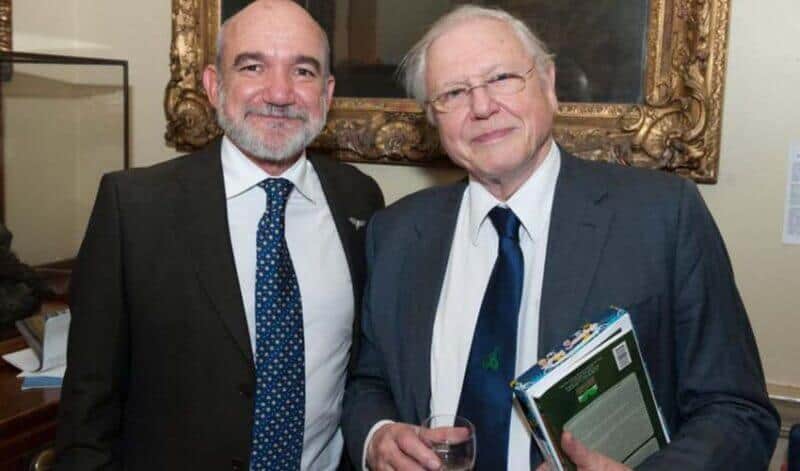

His efforts with the lesser long-nosed bat earned worldwide recognition with the Whitley Gold Award in 2012. The award is presented annually by the British-based Whitley Fund for Nature. Medellín remembers the ceremony, when he received the prize from England’s Princess Anne and got to meet Attenborough, who did narrations for videos about the honorees.

“It was one-on-one, David Attenborough and myself,” recalled Medellín, who compared himself to a Justin Bieber fan upon meeting his longtime hero and role model. “We talked about everything — about life, bats, Mexico, everything.”

Medellín’s enthusiasm for the bats resonated with Attenborough, who not only pledged to do whatever he could to make a documentary about Medellín but made good on his promise a day later: five members of the BBC approached Medellín at a reception at the House of Lords to say that a documentary filmmaking crew had been assigned to him.

In 2013, the crew came to Mexico for three to four months of filming.

“I have nothing more than praise for the work of the BBC,” Medellín said. “They were extremely respectful of the bats, myself and the environment.”

Attenborough gave the species its memorable nickname of the “tequila bat.” The crew filmed it inside the caves of Calakmul, using infrared light so the bats would not see any light around.

The use of light came into play in a different way when Medellín was having a hard time tracking the bats. He came up with an unorthodox solution. Upon catching some bats, he would sprinkle them with UV dust. They would lick it and ingest it, and it would make their glowing guano easy to spot. According to the program, the dust is harmless to the bats.

A moving moment in the documentary shows the successful realization of Medellín’s goal: the lesser long-nosed bat was taken off the endangered species list in Mexico in 2013, then delisted in the U.S. four years later.

As Medellín has tracked the bats across Mexico, he has sought to raise awareness about their importance. In the past, he said, people wrongly associated them with vampire bats and attacked the caves where they reproduced.

“Out of fun, they would throw rocks at bats, dynamite them, gas them, trying to get rid of vampire bats,” he said.

He does advocacy work with local communities — including landowners near the 13 principal caves where the bats breed, as well as elementary schoolchildren in these areas. Medellín praises the role of women in the community as well for imparting his message to their families and neighbors: “It’s an incredible opportunity for me to understand socially how information travels within a society,” he said.

He’s also urging the tequila industry to counter a trend of what he describes as cloning agave shoots to maximize alcohol production, instead of relying on bats for pollination. He questions whether cloned plants would “adapt to the conditions of climate change, agricultural pests, any other situation.”

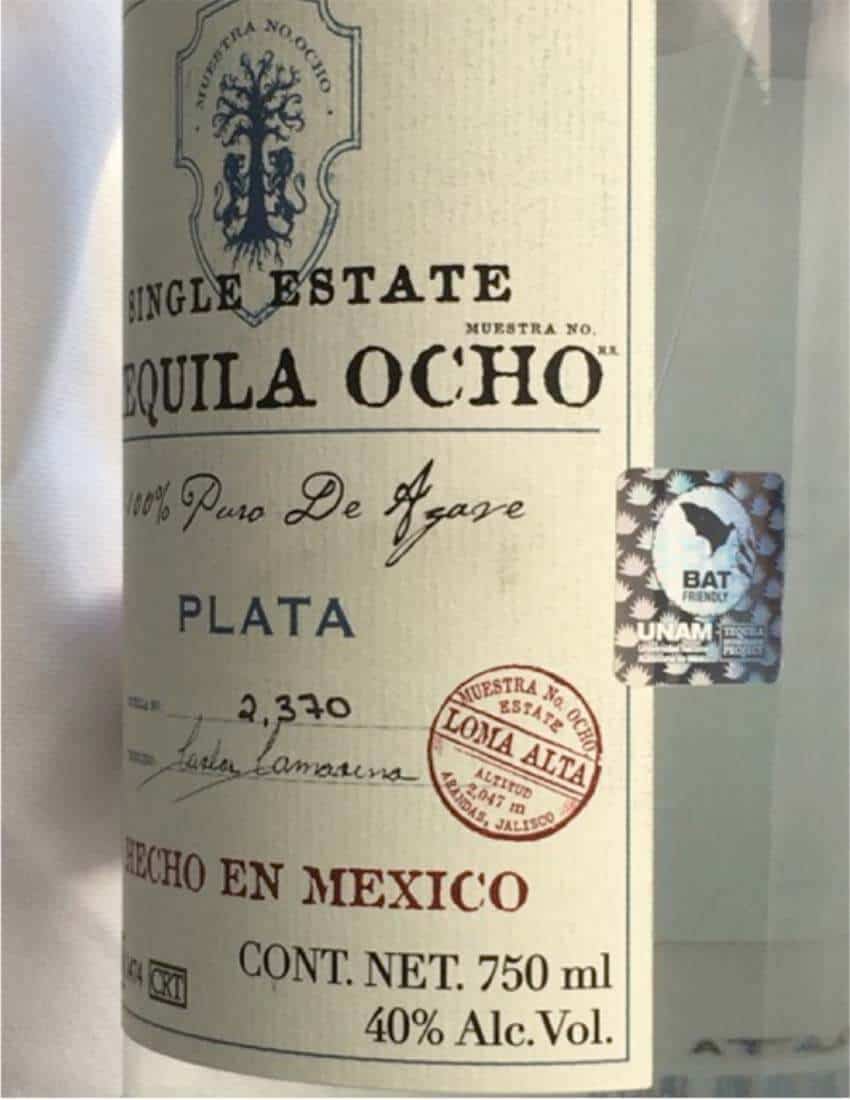

In 2013, Medellín joined forces with some of the most prominent members of the tequila industry [to] “basically convince [them] that they should allow 5% of their plants to flower,” with the resulting tequila being labeled as bat-friendly, he said.

In Mexico, he said, bats have avoided a more recent threat — stigmatization due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“When this news [of COVID-19] started to come out in February and March of 2020, in many countries in the world there was a war on bats,” Medellin said. “It didn’t happen in Mexico. There was not a single instance of people killing bats because of fear of the coronavirus … People in Mexico already know bats are our friends.”

According to Medellín, there is “no evidence whatsoever that bats gave us COVID.”

And in general, he said, bats “do nothing — nothing — to deserve the bad reputation they have.”

The documentary shows him doing all he can to defend the reputation of the lesser long-nosed bat.

“The people [living] behind all the caves nearby, the community living nearby, they never knew that [for] pulque, agave, tequila, these [bats] are the heroes,” he said. “I would give them pictures, evidence, proof. They immediately became bat allies.”

• “The Bat Man of Mexico” episode of Nature is available to view on the PBS website.

Rich Tenorio is a frequent contributor to Mexico News Daily.