Although it is one of Mexico’s best-known archaeological sites, the ruins of Teotihuacán in San Juan Teotihuacán, México state, never cease to inspire awe.

One reason why is the way this ancient city’s remains loom so large, not only historically but also physically: on the ruins’ east side, the Pyramid of the Sun, measuring 216 feet in height, stands majestically above the Avenue of the Dead.

About half a mile away, at the northern end of the avenue, stands the Pyramid of the Moon, 140 feet tall and facing south towards the Ciudadela (the citadel), where another, much smaller pyramid — the Temple of Quetzalcóatl — is located.

At its peak, sometime around A.D. 450, the city covered between eight and 14 square miles (different sources give different areas), and its population is estimated at 150,000 to 250,000.

This mysterious Mesoamerican city, which still holds secrets, was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987. If you spend time in Mexico but never made a point of seeing this site, you’re missing an important piece of Mexico’s ancient history. Teotihuacán influenced cities and civilizations throughout Mesoamerica, including the Cerro de las Mesas (Hill of the Mesas) in Veracruz and the Monte Alban site in Oaxaca. It influenced Maya civilization as far south as Guatemala.

This influence may be seen in its buildings and pyramids’ construction methods and by the presence of cruces punteadas (pecked crosses), conventions originating in Teotihuacán and shared by later pre-Hispanic civilizations.

These pecked crosses’ purpose isn’t known — archeologists have postulated everything from astronomical devices to urban maps to games — but their presence in far-flung cities suggests that they were important.

Despite its size, apparent importance and influence, no one knows who built Teotihuacán or why it was abandoned around A.D. 750. Even its actual name remains a mystery.

Teotihuacán, which in Nahuatl means “place where the gods were created,” is a name the Mexica gave the city sometime in the 1400s. They also gave Teotihuacán’s pyramids and other structures the names we know.

Carlos de Siguenza y Góngora, a 17th-century intellectual and New Spain’s official geographer, made Teotihuacán’s earliest recorded excavations. More extensive ones followed in the 1880s and continue through the present day, which have allowed archeologists to tease out a significant amount of Teotihuacán’s history.

Teotihuacán was probably settled by 400 B.C., although it didn’t develop into a city until a couple of centuries later. Archeologists divide its history into four periods known as Teotihuacán I, II, III and IV.

During Teotihuacán I, which lasted from 200 B.C. to 1 B.C., farmers began settling around the springs located in the area, and a city began to form. The city expanded tremendously during Teotihuacán II (A.D. 1–350). This growth is believed to have been partly due to the arrival of people from Cuicuilco, a city located in what is now Tlalpan, a borough of Mexico City.

People fled Cuicuilco after a series of volcanic eruptions sometime between A.D. 245–315. During this period, monumental structures like the Pyramid of the Moon and the Pyramid of the Sun were constructed.

Teotihuacán III (A.D. 350–650) saw the city reach its peak size, population and influence over Mesoamerica. During that era, the city’s believed to have hosted at least 150,000 people and around 2,000 buildings.

Then, during the period designated as Teotihuacán IV (A.D. 650–750), the city began its collapse. Burn marks on a number of buildings had initially led archeologists to speculate that its destruction was due to an invasion, but further investigations have revealed that the burning was restricted to structures occupied by the ruling class.

It’s now believed that the destruction was most likely due to a local uprising against the city’s rulers. By A.D. 750, the city was abandoned.

Although much remains unknown about the city, excavations and research have yielded significant information.

The Pyramid of the Sun’s purpose is still uncertain, however. But it’s aligned with Cerro Gordo, a sacred mountain in México state, where rain petitions are still conducted by traditional shamans, so it’s possible that the ancient residents conducted similar ceremonies atop the pyramid, where archeologists believe a temple once stood.

According to a paper published by Ivan Sprajc in the journal Latin American Antiquity, the Pyramid of the Sun is aligned to record sunrise and sunset on specific days, allowing it to be used as an observational calendar.

Tunnels and caves were first discovered under the pyramid in 1971. And although its interior has yet to be fully explored, archeologists have found a collection of obsidian, clay fragments and figures in one area and, beneath the pyramid’s summit, two pillars and a figure of Huehueteotl, the god of fire.

The Pyramid of the Moon was built successively from A.D. 1 to 350. A new pyramid was built on top of the previous one, resulting in a larger and larger structure.

The pyramid was the Teotihuacán’s religious center and apparently the site of ritual sacrifices, as human and animal remains have been uncovered there. Its 12 small platforms may have used to view sacrifices.

At the southern end of the Avenue of the Dead is the Ciudadela, a complex occupying over 38 acres. Within is the Temple of Quezalcóatl, the feathered serpent god. Large serpent heads line the staircase leading to the top, and more line the its walls, alternating with figures of Tlaloc, a rain god. Shells and serpents have also been carved into the walls.

All these figures are associated with water or rain. A number of graves of sacrificial victims have been found at the site, including one mass grave containing 130 skeletons.

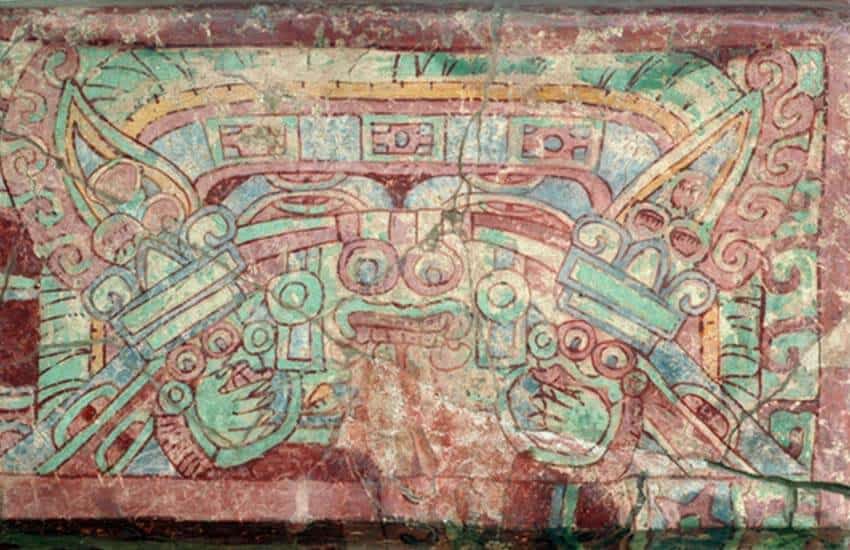

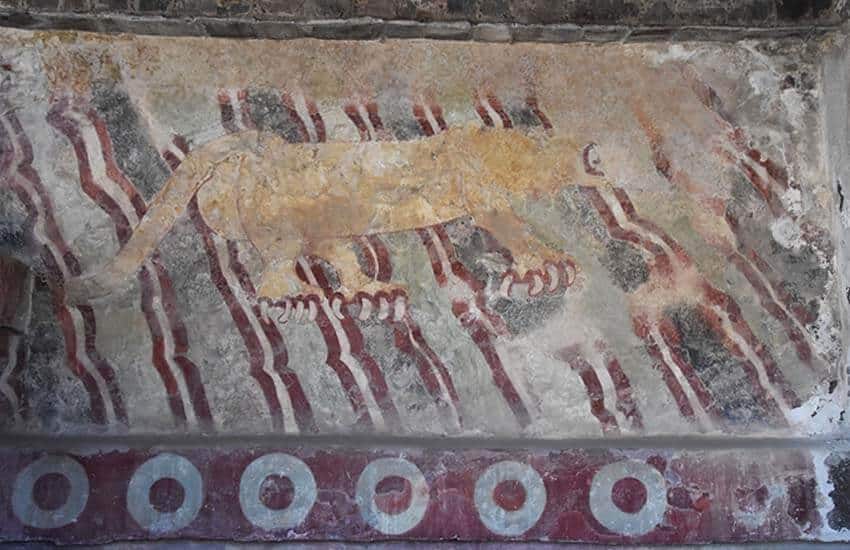

Teotihuacán’s buildings were once painted with bright colors and murals, some of which can still be seen. Portions and recreations of other murals can be viewed at the Museo de Murales Teotihuacano Beatriz de la Fuente onsite. The Museo de la Cultura Teotihuacana there contains more than 600 excavated artifacts.

Teotihuacán costs 80 pesos to enter. Parking is extra. Gate 2 provides a spectacular first view of the Pyramid of the Sun.

Plan on two hours to see the ruins and an hour for the museums. Also, the site has precious little shade, so take a good sun hat and sunscreen.

Joseph Sorrentino, a writer, photographer and author of the book San Gregorio Atlapulco: Cosmvisiones and of Stinky Island Tales: Some Stories from an Italian-American Childhood, is a regular contributor to Mexico News Daily. More examples of his photographs and links to other articles may be found at www.sorrentinophotography.com He currently lives in Chipilo, Puebla.