After heavy criticism of the president in last week’s column, on this point, I at least partially agree with him.

That asterisk of mine is admittedly a gigantic one, but I like to start with the positive.

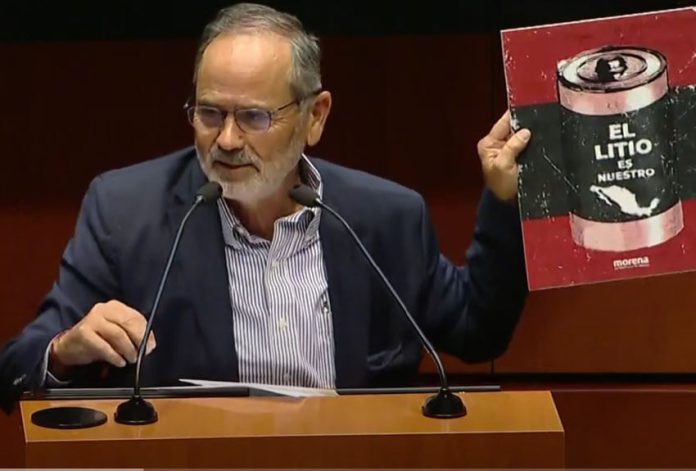

The slogan refers to a reform to Mexico’s Mining Law approved in Congress on Tuesday that nationalizes lithium. The change in the law explicitly prohibits the offering of lithium concessions of any kind to any private companies — foreign or Mexican — putting the government in charge of all aspects of managing Mexico’s lithium via a to-be-created public entity. The law goes into effect immediately, and according to its text, the government must create that managing entity within 90 days of the law’s passage.

If a natural resource that can be extracted has originated on Mexican soil, then it rightfully belongs to Mexico — at least more so than to China, Russia, Canada or the United States. If this lithium is eventually exploited — and the state’s ability to do so on its own is very much in question — then Mexico should reap the rewards from that extraction (as well as the responsibility for the inevitable environmental damage it causes).

But as National Action Party Senator Gustavo Madero pointed out earlier this week, however, the Mexican Constitution already established de facto state ownership of lithium in 1917: Article 27 of the document says, “… in the Nation is vested the direct ownership of all natural resources …”

So why the reform if there’s nothing to actually reform?

Many critics have speculated that this nationalization move was simply a balm to soothe the pain of failing to pass the reform that would have guaranteed the Federal Electricity Commission (CFE) 54% of the energy market.

Predictably, the president has designated those who voted against that reform as “traitors to the nation,” an unsurprising response given his habit of lashing out at anyone that criticizes or prevents him from pushing through something he wants.

But back to the lithium. It’s ours. Well, “ours.”

To what extent will the Mexican people benefit if the state does actually manage to both start and run its own lithium mining company?

Before Pemex was privatized, I remember one particular slogan repeated against privatization: “The petroleum is ours.” Sounds familiar, right?

It’s a phrase I didn’t quite understand, though: could Mexicans simply go to the gas station and fill up their cars free of charge because it was “theirs?” Were average citizens getting monthly checks in the mail representing their designated portion of petroleum? Certainly not.

Still, even if it’s mostly symbolic, I think it’s fair to say, “No, you cannot come into our country and mine our lithium resources.”

Of course, several foreign companies are already doing so. (When asked about it, the president responded, “These contracts have to be reviewed.”)

If mining experts are to be believed, there is absolutely no way that Mexico will establish a state lithium mining company while AMLO is still in office; in addition to lacking the funds, it simply wouldn’t be possible in that short amount of time. And given the inefficient track records of our other national companies, I’ve personally got my doubts about the viability.

This is probably for the best as, ironically, lithium – used to make batteries for “green” technology like electronic vehicles as well as batteries for everyday electronics like our cell phones — is extremely dangerous and environmentally hazardous to extract. It also uses tons (literally) of water per minute, and Mexico’s got enough trouble with a lack of water.

In addition to this, Mexico’s supply of lithium seems to be held within clay deposits, which experts tell us is extremely expensive and difficult to extract.

The president will surely say that he “has other information.” Or perhaps he’s banking simply on not being in office anymore by the time a state company could actually be formed.

In the meantime, I highly suspect that the private companies already exploring Mexico’s lithium will be allowed to quietly go about their business. After all, not quite a year ago, Economy Minister Tatiana Clouthier said in a radio interview that Mexico was interested in a public-private partnership with lithium mining companies, suggesting that the state might seek to secure a 51% stake in the sector. And around the same time, a Morena lawmaker and close AMLO ally told the news agency Reuters, “We’re convinced that we need private investment, and we’re allies of domestic investors and also foreign investors who respect us,” hinting at plans for a regulated but market-friendly lithium sector.

But stating that “the lithium is ours” (uh … yeah, we know) is good politics and also serves to give the illusion that we’re marching happily toward the president’s goal of complete energy independence by the end of 2023.

I’m concerned about the environment, though, a concern that the president does not seem to share in the least. The goal is energy (and economic) independence above all else, despite the cost to the environment and despite commitments that Mexico made under previous administrations to cut emissions.

Sembrando Vida and a handful of hydroelectric dams are just not going to cut it.

That said, I know that demand for energy will not go away. We need electricity. We need batteries for our phones and computers. We need at least some vehicles. And as the story of lithium shows, even when we want to be “green,” it’s a nearly impossible task.

You might buy an electric car to avoid pumping pollution into the air, but the battery used for that car requires lithium, the extraction of which is very dirty and very dangerous (a caveat, though: most experts agree that the overall damage to the environment is still less with an electric car).

We also depend on lithium to store energy from green technology like solar and wind energy. After all, the sun doesn’t always shine, and the wind doesn’t always blow. So far, lithium is one of the only ways we have of stocking up on it.

Is there any way to win?

I pray that we can find a “clean” way to get what we need (though mining is never clean) or find another way to store our energy. But until we do, this is what we’ve got.

For now, I’m reminded of the Netflix satirical film Don’t Look Up. In the movie, a huge meteorite is headed straight for Earth, guaranteed to destroy it if it hits. A plan is quickly made to pulverize it, avoiding disaster…until some eccentric Elon Musk-type character tells the president about the lucrative potential for mining it. So a new plan is formed to simply break it up so that “jobs can be created and money made.”

Unsurprisingly, it doesn’t work, and the Earth and everything on it is destroyed.

The moral? If we continue thinking we can trick the gods, there is no way around paying for that. Nature will do what it does despite our human, fallible will. Hopefully, AMLO and all the other world leaders will realize how seriously at stake our future is before it’s too late. It’s the hope.

But in the meantime, I’ll be staring at the sky, not holding my breath.

Sarah DeVries is a writer and translator based in Xalapa, Veracruz. She can be reached through her website, sdevrieswritingandtranslating.com and her Patreon page.