Ajijic is widely noted as one of Mexico’s main art towns. Yes, much of that today is because of the many foreign artists and collectors, but I’ll argue that even more important are locals who have been nurtured in this direction since the mid-20th century.

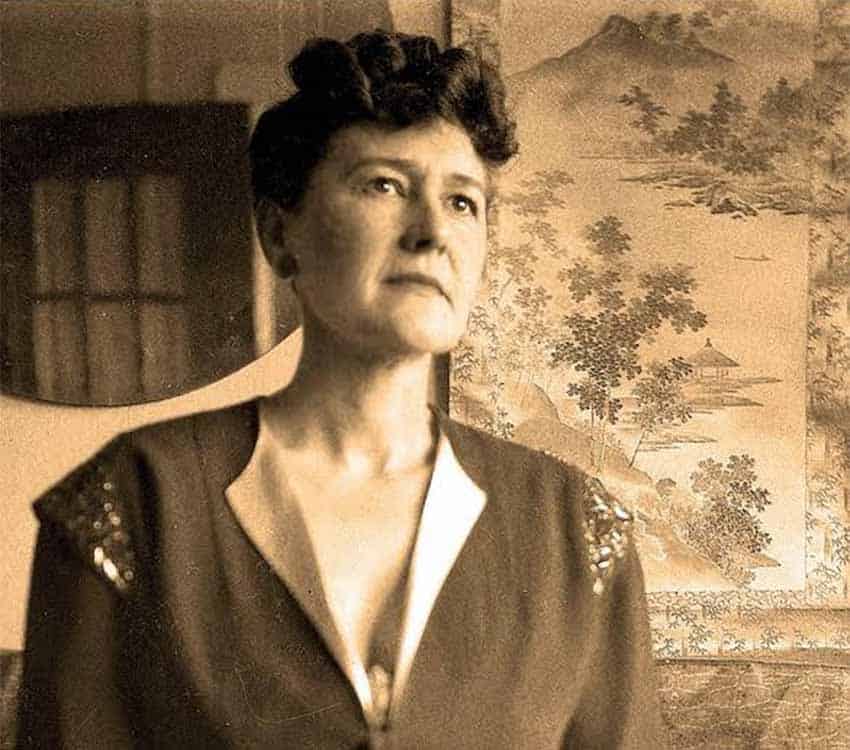

Ajijic was a relatively unknown place when American Neill James arrived here in 1943. An international travel writer, she had been on several continents during the interwar period.

Her foray into Mexico took a turn for the worse when she broke her leg on one volcano and got nearly buried by the ash from another.

Or as she put it: “I fell on Popocatépetl; Paracutin fell on me.”

She was taken to Ajijic to recuperate, where she wrote her most famous book Dust on My Heart — which also signaled the end of her travel writing career. She had found “home.”

Her decision to spend the rest of her life there was not just the great weather, it was also the people. Entrepreneurial herself (necessary since she was not independently wealthy as some stories claim), she got involved in the community to help people help themselves.

Most of these efforts were in education, first with a library and then a program to teach art to local children in 1954. The program was not just about creating art but selling it as well. She partnered with local teacher Angelita Aldana, who taught almost all of the first generations of alumni.

Promising students received scholarships to an art institute in San Miguel de Allende or to the University of Guadalajara.

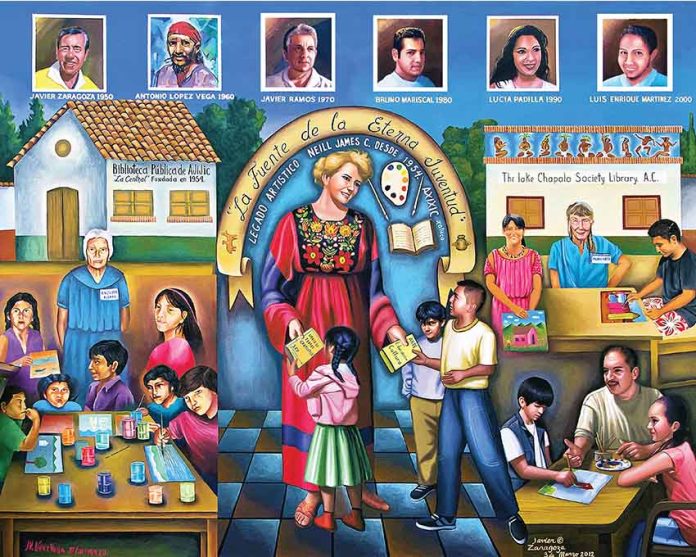

James died in 1994 at nearly 100 years of age, and her program is still going strong at the Lake Chapala Society (LCS), the largest expat organization in Mexico. She did not found the organization, but she did bequeath her house to them, their main facility. Alumni Jesús López Vega and Javier Zaragoza painted a mural honoring her and the children’s art program at the facility, which has over the years trained many local children, many of whom went on to have art careers both in Mexico and the United States.

Some went to have careers in the United States, while others developed their careers in the Chapala area, where their influence is prominent in many local galleries and murals. Their art is no small part of the reason why many foreigners come to live “lakeside” and stay.

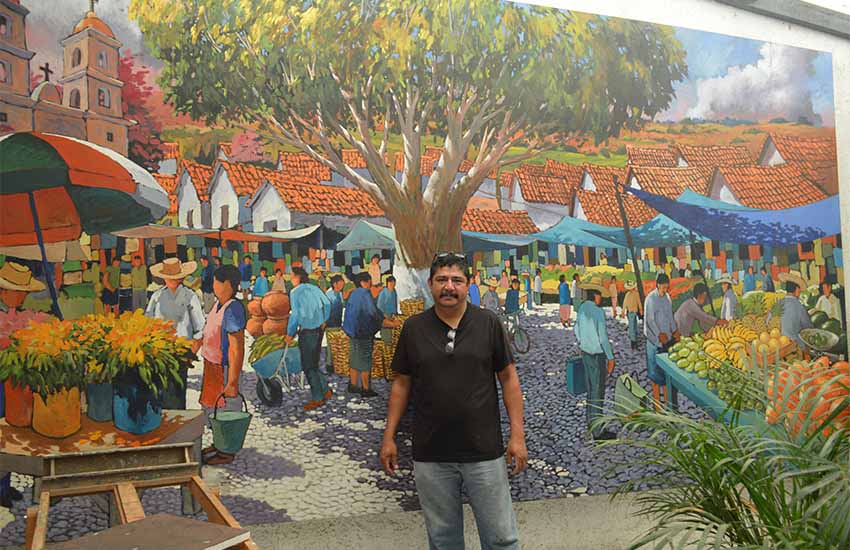

One of James’s first success stories was Javier Zaragoza, a 1950s graduate who would go on to have a multi-decade commercial art career in the United States before returning to Ajijic to open a gallery. He says that at that time, the idea of being an artist was far beyond his dreams in a tiny town, no matter how much talent one might have.

Brothers Antonio and Jesús López Vega are 1960s graduates, both fixtures in the town’s mural and gallery scenes. Both mix folkloric Mexican imagery with surrealism, heavily influenced by their grandmother’s stories about the lake and the region. Antonio is the better-known of the two, having had shows in prestigious venues in Mexico City.

However, both remain in Ajijic, creating murals and teaching the next generations of Ajijic’s artists.

The Padilla family also has benefitted from the program, starting with early student Florentino Padilla, a contemporary of Javier Zaragoza. He received a scholarship to San Miguel, then in the 1970s moved to San Francisco, where he painted a mural.

His niece, Lucia Padilla, did not know him well, but seeing him paint one time inspired her. She, too, attended the program and has worked in art on and off since the 1990s, including modeling for painters.

She is the only woman alumni of the program featured on the Lake Chapala Society’s mural. Her 11-year-old daughter, Jennifer, is the next generation and, Mom, of course, fully supports her efforts.

Perhaps Ajijic’s most famous mural was done by 1978 graduate Efrén González. Although he did the allegory on the primary school’s main facade, the main attraction is the rows upon rows of red clay skulls with names. Each of these are lit up on Day of the Dead.

Ever the workaholic, he teaches, runs several art businesses with his sons and this past summer opened the town’s first art museum.

One of the most recent success stories is Luis Enrique Martínez Hernández. Like many artists, he began drawing as a small child, but unlike many, his parents encouraged this, even though they were poor caretakers of a hacienda in San Juan Cosalá, Jalisco. At the Lake Chapala Society, he was mentored by various alumni of the program and went on to exhibit with his work influenced by impressionism and surrealism.

Most of the living Mexican artists in the town are linked to the school, but not all. In 1977, James started the short-lived Young Painters of Ajijic, which allowed alumni and others to exhibit their work on Sunday afternoons on the property. It would be the forerunner of the current Asociación de Artistas de Ajijic/Ajijic Society of the Arts.

Today, newcomers like Goretti Chavira and Orlando Solano Álvarez work to make their name, completely independent of the school.

James never had any biological children. But in a sense, she is still producing young artists, some of which are second- and even third-generation participants. The program is still running strong at the Lake Chapala Society, with 90 registered and with at least 30 attending Saturday classes.

Javier Zaragoza, who has taught as a volunteer here for 20 years, says that only a few stay on and show promise to be artists, but perhaps more importantly, the program shows children that they have value and can do whatever they like if they want it enough.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 18 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.