The rough-hewn walls of Finca Margaritas’ main room are adorned with photos that trace the five generations of coffee farmers that worked this land.

Stalwart and serious, groups of men, women and children stand in front of this very same structure, built in 1871 and still standing almost 150 years later in Pluma Hidalgo in the southern Sierra Madre of Oaxaca.

Today, Adriana and Cole Ramírez are the last in each of their lineages to take over two wild tropical coffee plantations that dot one of the highest peaks in the area. Adriana’s sing-song accent, slightly distinct from Cole’s from growing up in coastal Puerto Ángel, is hypnotizing as she weaves the story of the plantation.

“My in-laws were the Romeo and Juliet of Pluma Hidalgo. They lived on neighboring fincas and Cole’s father’s uncle, Uncle José, hated Cole’s mother’s grandfather. So much so that when Tío José brought electricity to Pluma Hidalgo with his hydroelectric generator, Cole’s mother’s family was the only family in town without electric lights. When they were first married they lived in a large, modern building built by Cole’s mother’s family – and only their bedroom had electricity.”

These small-town dramas, the stuff of Gabriel García Márquez novels, fill the annals of Pluma Hidalgo. And the tropical vegetation and hint of sultry humidity in the air only add to the vintage charm. The town and the surrounding area has been a center of coffee production in Oaxaca for 150 years. Most Oaxacan towns were pre-Colombian indigenous settlements, but Pluma was different — it was founded strictly with the aim of growing coffee.

In the 1800s businessmen from Miahuatlán, another municipality in the southern Sierra, were making a killing selling cochineal dye on the world market. Then in 1863 the Germans created the first artificial dyes and the market tanked. These wealthy men started looking for a new industry to invest in and discovered coffee as an emerging export in the state of Veracruz.

Cole’s family was one of the first to come to Pluma to plant café. His ancestors built the Swiss chalet-like Finca Margaritas in the middle of wild chestnut and papaya trees. The finca passed through various hands through the generations, and at one point was producing a 1,000 sacos of coffee a year (about 70,000 kilos).

But that heyday was pre-1992 when the International Coffee Agreement disintegrated (causing world prices to bottom out), and before Hurricane Paulina, which virtually deforested the mountain in 1994 and reduced production by 90%. Most plantation owners abandoned their land, no longer able to survive cultivating what was once one of the world’s best beans.

“My father told me when the hurricane came through that it would take 20 years for the land to recuperate,” says Cole, “It’s been just over 20 years and the old-timers in Pluma are saying the forest is finally returning to what it was.”

Typica, the first arabica bean variety brought to the Americas from Africa, is highly sensitive to strong winds, coffee leaf rust and insect plagues. But it is also considered some of the best coffee in the world and is grown in a limited number of places, among them Jamaica, Hawaii, Ethiopia and Pluma Hidalgo, Mexico.

While some of Pluma’s coffee planters have been persuaded to trade typica for hearty and higher-yield varieties, Adriana and Cole believe this high-quality bean is the key to growing gourmet coffee in Pluma.

“My husband’s No. 1 passion in life is coffee,” says Adriana, “He learned everything about growing from his maternal grandfather. When he was 16 he came here and he learned all the old, romantic traditions of coffee cultivation. Most producers just produce, they just do what they can to get by, but my husband has studied everything he can about coffee.

“The same thing that has happened with wine is happening with coffee. People are specializing in the production of excellent coffee and the drinking of excellent coffee. We are trying to control every part of the production chain in order to end up with the kind of excellent coffee that people are looking for.”

Pluma the town, a tranquil piece of mountain paradise with about 1,300 residents, was also deeply scarred by the coffee exodus of the 1990s, with many residents leaving for work in other parts of the country and the United States. Even today, Adriana tells me, it’s difficult to find enough workers for the harvest.

But perhaps the current “third wave” coffee connoisseurs will help bring investment and jobs back to Pluma. Francisco Villarreal, from the north of Mexico, is a young and ambitious investor who was drawn to the possibilities of the region.

“My family was already working with local coffee growers in Oaxaca and we had the chance to go to Europe and the United States to promote their coffee. In the majority of places where we went people asked us if we were selling Pluma coffee. When we returned from the trip we dedicated ourselves to investigating what and where Pluma coffee was.”

Upon discovering the region and tasting the coffee, Villarreal decided to purchase land for his own coffee plantation — Manto Niebla. He now owns 70 hectares of mountaintop where he has planted between 60,000 and 70,000 coffee plants since he started in 2016. He grows Geisha, Marsellesa and, of course, typica beans.

“It’s a really great sign that people are reactivating the plantations, even though it’s still a small percentage of what were abandoned. New varieties and growing practices are also allowing a greater control over leaf rust and allowing growers to have bigger and better production, therefore making the farms more successful,” says Villarreal.

The comeback is there, albeit slow and laborious, and the signs are everywhere. A brand of Pluma coffee was chosen by Starbucks for an exclusive coffee bar in Mexico City. Oxxo, the country’s biggest convenience store chain, announced it will now carry Pluma coffee as a nod to the traditional coffee-producing regions in the country.

And at least a few dozen tourists can be seen ambling through the streets of Pluma, stopping to buy a bag or two of the town’s famous beans.

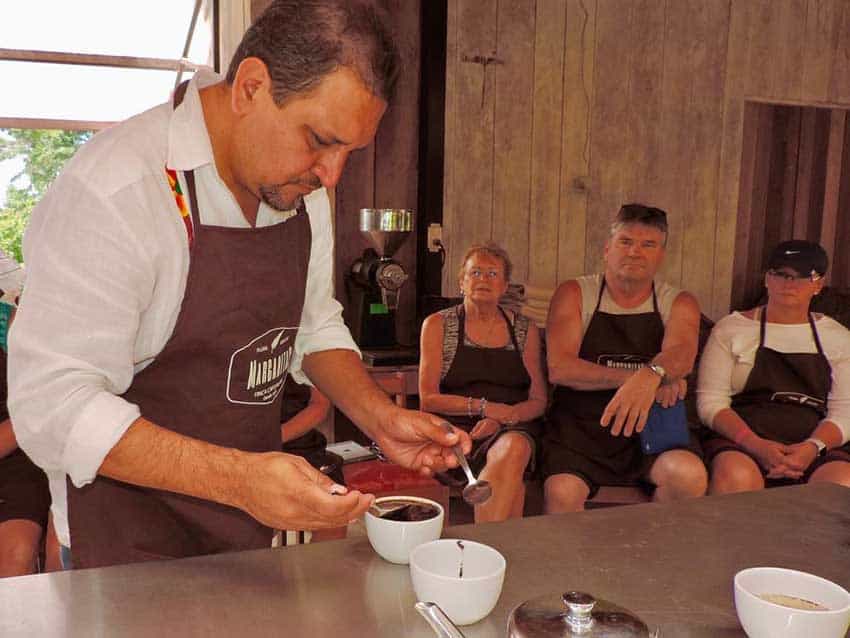

The ecotourism of this region will be just as important as its coffee for its future. In biodiversity alone, it offers much for coffee and nature lovers. That’s why Adriana and Cole have set up a glamping (glamour plus camping) site on their property and offer weekly coffee tours and tastings to tourists who drive up in minivans from nearby Huatulco.

“I think the region’s towns have a big opportunity to prosper,” says Villarreal, “as much from the production and sale of coffee as tourism.”

And really, who can resist the combination of the two? I know I was enchanted slipping from my luxury tent to sidle up to the coffee bar at Las Margaritas and have Cole hand me a steaming hot cup of Pluma typica with a dollop of steamed milk.

After years of performing tastings, his sense of taste and smell are far more sophisticated than mine, but sitting in the cool dampness of a Pluma morning, my hands wrapped around a steaming mug, I gave myself a break when I wasn’t able to pick out the scent of limes in my cup.

In delightful moments such as these, it’s better just to sit back and enjoy.

Lydia Carey is a freelance writer based in Mexico City.