The procession for the posada begins, as do virtually all processions in San Gregorio Atlapulco, Mexico City, with cohetes (bottle rockets) exploding overhead.

“Cohetes announce the beginning of the procession,” said Aristides Norberto Enriquez Nieto. “It’s like when the church rings its bells. It is also to give thanks.”

Posadas take place each year all over Mexico from December 16–24 and are reenactments of Mary and Joseph’s search for a place to sleep. As far as I can tell, though, there is no mention in the Bible of them using cohetes during their search.

Posadas were begun in Mexico in 1587 when Fray Diego de Soria, the director of the San Agustín de Acolman monastery (located in what is now the state of México), obtained permission from the Pope to hold special Masses during nine days in December. Although posadas originated in Spain, they are most closely associated with Mexico. Like many Mexican celebrations, they have underlying elements of indigenous culture and religion.

The Aztecs celebrated the birth of Huitzilopochtil, their god of war, during the month called Panquetzaliztli, which corresponds to our month of December.

“There were 20 days of ceremonies to honor Huitzilopochtil,” says Javier Marquéz Juaréz, who has studied Aztec history. These ceremonies included celebrations in homes, processions and special foods.

“December 21, the winter solstice, was considered to be the birth of Huitzilopochtil,” Marquez continued.

Aztec celebrations culminated on December 25.

The nine days of posadas each represent one month of Mary’s pregnancy. “The first eight are organized by mayordomos [lay religious leaders],” says Marquéz. “The ninth and final one, on December 24, is organized by the padrino del niño del pueblo.”

Before the procession begins, people gather in the large yard in front of Enriquez Nieto’s home; he’s the padrino.

“I waited three years to be a padrino,” he said. “My father and my grandfather were padrinos. To be a padrino, one needs to ask the current one … one must follow the rules and regulations of the church. You’re an example of the church. I did it to thank God.”

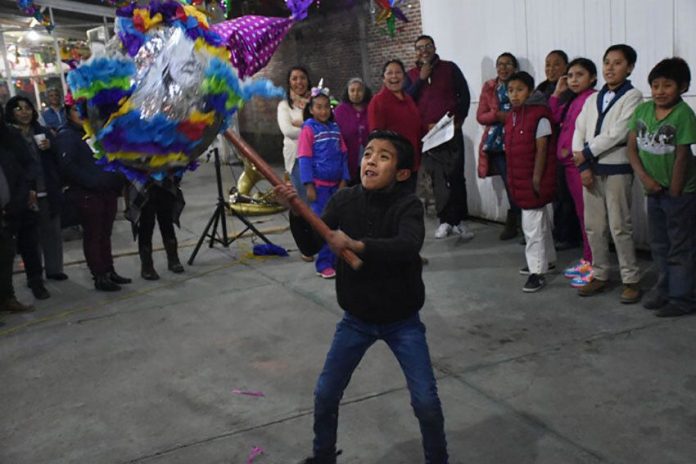

There is food — lots of food — a band, drinks and a piñata, which is traditionally included during posadas, hanging from a wire.

“The piñata is a Christian symbol,” explained Marquéz. “It is a star with seven points, each point representing one of the cardinal sins.”

Children whack at the piñata with a small stick, hoping to break it open, releasing the candy inside. “It is broken to destroy the sins,” said Marquéz.

After the piñata is dispatched, cohetes are lit.

“Cohetes let the Chinelos know it is time to come and form the procession,” said Enriquez. Chinelos are dancers famous for their colorful flowing costumes, large hats and masks. They originated in Morelos during the colonial era as a way to mock European dress and mannerisms, and over time their popularity has spread to other Mexican states.

There are now groups in Xochimilco (which is where San Gregorio is located) and Milpa Alta, two boroughs in Mexico City, where Chinelos often participate in celebrations. They perform a simple dance called the brincón (jump), which involves a sort of jumping up and down in place to music and which they are somehow able to perform for hours.

Chinelos are another element of posadas not mentioned in the Bible, but, said Enriquez, “Chinelos add more joy to the fiesta.”

As the procession leaves Enriquez’ home, his niece and nephew, dressed as Mary and Joseph, are lifted onto a donkey that they’ll ride to the church. Enriquez, as padrino, gently places a figure of the baby Jesus onto a white cloth which he and his wife carry.

More cohetes and other fireworks — some of them surprisingly large and dangerous-looking — are lit as the procession makes its way through the pueblo, where the streets are lined with people holding candles and sparklers. The procession makes several stops along the route, and each time it does, there’s a bit of theater. And when the procession pulls up in front of the church or a chapel or a person’s home, the crowd asks for permission to enter. Like Mary and Joseph in the Bible, they’re denied entrance at all except the last stop, where the doors are finally opened.

On nights where the final stop for a posada is the church, a Mass is held. On December 24, the Mass is held at midnight. But on nights where the final stop is a person’s home, more food and drink are served and the fiesta continues.

Joseph Sorrentino is a regular contributor to Mexico News Daily.