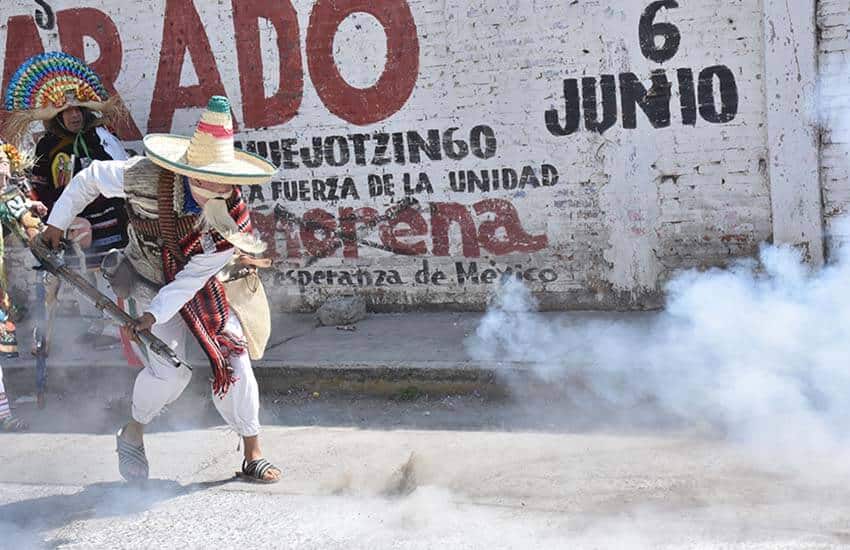

In Huejotzingo, Puebla, Carnival is huge, extremely noisy, very colorful and a lot of fun. And there are a lot of guns.

Officially, this year marked the 154th anniversary of Carnival, but according to Huejotzingo culture and tourism director Edgar Aguilar Teyssier, it’s much older.

“In reality, Carnival has [gone on for] eight centuries,” he said. “What is correct is that this is the 154th anniversary of the militarization of Carnival — that is to say, when it started to celebrate the battle of Cinco de Mayo.”

Carnival’s true origin is linked to the beginning of the farming cycle, when indigenous groups started preparing the land for planting, but despite it’s co-opting over a century ago, it’s still an important event in Huejotzingo, Aguilar said, estimating that 20,000 to 25,000 residents would participate this year.

“[Huejotzingo] has a population of about 90,000, so one of every three participate in the parade, and really, 100% of the population is immersed in Carnival,” he said. “If you are not a dancer, you are someone who makes food or makes clothing.”

Participants are grouped into four “battalions,” one from each of Huejotzingo’s neighborhoods. A band accompanies each, with a “general” leading them.

Each wears a distinctive costume and carries fusiles talladas, elaborately carved and very loud muskets, which have caused injuries and even deaths on occasion, Aguilar said. But, he added, “there are 25,000 participants, and barely 10 people are hurt.”

In Huejotzingo, Carnival commemorates three events: the defeat of the French in Puebla on May 5, 1862; the story of a kidnapping of a mayor’s daughter by Agustín Lorenzo, a bandit; and the first Catholic indigenous wedding.

At 9:30 a.m., members (called carnavaleros) of the Indian Batallion of Barrio 3 entered the municipal cemetery.

“We are here to honor the generals who have died,” said Alberto Santa María Cruz. He’s one of many mandarines responsible for helping to keep the peace. Guns were fired and people drank and danced as a band played and then the battalion marched from the cemetery, stopping in various neighborhoods.

As the day progressed, the energy increased, guns were fired more frequently and the dancing got wilder. In 2013, five tonelades (11,023 lbs.) of gunpowder were used at this event, and I doubt they used one gram less this year.

A break at 3 p.m. allowed participants to rest and get food. At 4 p.m., a ceremony commemorated the first Catholic indigenous wedding, followed by a reenactment of Lorenzo the bandit making off with the daughter of the town’s mayor.

Finally, it was time for the quema del jacal (burning of the jackal), where a small palm hut was burned, representing the end of all Mexican wars, from pre-Hispanic times up through the Revolution.

Carnival in Huejotzingo is crazy, loud and expensive. Guns cost 3,000 to 5,000 pesos (US $150 to $250), and costumes as much as 50,000 pesos (US $2,500).

When asked why Carnival must continue, Hilario Oliver Saloma threw his arms open wide.

“For tradition,” he said loudly. “It is for tradition.”

I left Huejotzingo with my ears ringing as if I’d just attended a Who concert circa 1970. Some hairs on my right arm were singed from getting a bit too close to a carnavalero firing a gun. I was exhausted from photographing for seven hours. My head hurt.

But, as people say in Mexico, “Vale la pena.” It’s worth it.

Joseph Sorrentino, a writer, photographer and author of the book San Gregorio Atlapulco: Cosmvisiones and of Stinky Island Tales: Some Stories from an Italian-American Childhood, is a regular contributor to Mexico News Daily. More examples of his photographs and links to other articles may be found at www.sorrentinophotography.com He currently lives in Chipilo, Puebla.