Zacatlán, Puebla draws thousands of tourists annually for its apple harvest events and for the murals that adorn several streets and buildings. But should you find yourself in this Magical Town, one attraction in Zacatlán that doesn’t get as much attention but is worth checking out is the Museo de la Relojería (The Clock Museum), which calls itself “a completely interactive museum,” where you can touch devices that are hundreds of years old, listen to some of them tick and chime, and watch the manufacturing of clocks done by people who have dedicated their lives to creating devices of beauty that are also functional.

Humans have been trying to accurately measure time for thousands of years, using a variety of instruments. Examples of these devices — both actual and reproductions — may be seen at this museum, named for Alberto Olvera Hernández, founder of Relojes Centenario (Centenary Clocks), the first manufacturer of monumental clocks in Latin America, currently located in Zacatlán.

The museum, which opened in 1999, is located on the second floor of the Relojes Centenario building. Visitors first pass through the area where clocks are made (there will be more about the company later), where an exhibit is set up called, appropriately enough, El Hombre y la Medición del Tiempo (Man and the Measurement of Time).

A mural designed by Carlos A. Olvera Charolet, the founder’s son, occupies one wall of the stairwell leading to the museum. A portrait of Alberto is at the top center of the mural, and he’s surrounded by important people and events in his life. His wife appears as a silhouette, and below are 12 figures that represent his children. In addition, there are drawings of books he studied, a violin, which he played, and, of course, a variety of timepieces.

When you enter the first room it gets a bit more interesting, with examples of sundials, one of humanity’s earliest methods for quantifying and measuring time, used by the Egyptians as early as 1500 B.C. and other civilizations like the Babylonians, Greeks and Mayans. The museum has at least 33 different types of sundials on display, including vertical and horizontal examples, and ones designed for use on the equator.

You can also see how water clocks worked here. Also known as clepsydras, they were an improvement over sundials for timekeeping since they didn’t depend on the sun, but instead on a constant flow of water from or into a container. They were used by many civilizations, including the Romans, Native Americans and some in Africa.

The walls and cases are also jammed with examples of the many other devices humanity has used and continues to use, in some cases, to keep time: candles, hourglasses, pendulums, electricity, wristwatches and even atomic clocks. In one corner of the museum is one particularly important clock to Zacatlán, the first one made by Olvera.

Olvera born on a farm outside Zacatlán in 1882, became fascinated with clocks when he repaired a broken one in his family’s home. He began building that first clock, called the Reloj Piloto (Prototype Clock) in 1909 and finished it three years later.

In 1918, he decided to make his first monumental clock, which took him a year to build. That clock was installed in the Santiago Apostol church in Chignahuapan, Puebla, where it still keeps time. Three years later in 1921, Relojes Centenario opened in Libres, Puebla, eventually moving to Zacatlán in 1966. The name Centenario was chosen to honor the 100th anniversary of the end of the Mexican War of Independence.

Since its inception, the company has built over 2,000 monumental clocks. They can be found in churches, as well as government and office buildings, across Mexico, and in many other countries, including Argentina, Chile, Spain and England.

One of the most famous, and perhaps the most beautiful, is the floral clock located in Zacatlán’s zócalo, which was installed in 1986. The clock has two separate faces controlled by the same mechanism and plays nine different melodies.

A melody is played only four times a day—at 6 a.m., 10 a.m., 2 p.m. and 9 p.m. — and different ones are played at different times of the year. The company built another floral clock that’s located in Mexico City’s Parque Hundido (Sunken Park) which is in the Benito Juárez neighborhood. At 78 square meters (840 square feet) it’s one of the world’s largest.

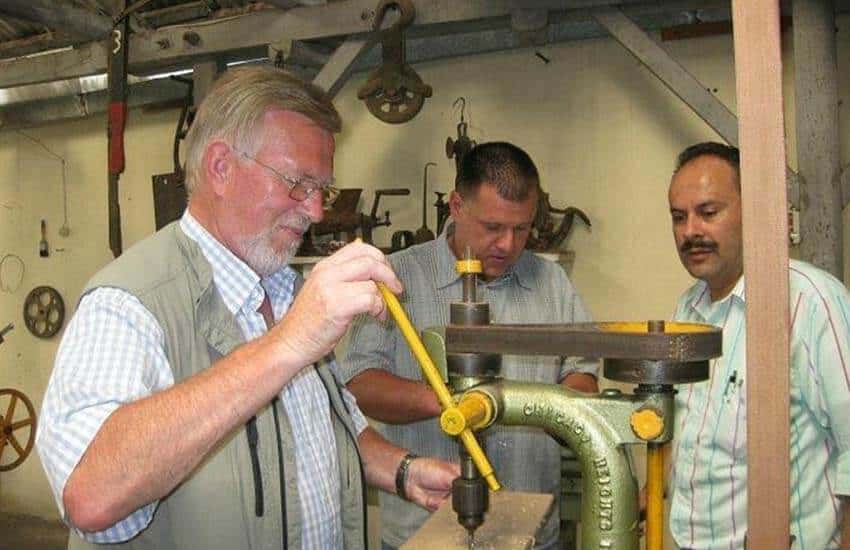

In addition to the museum, people may tour the factory that makes monumental clocks, a surprisingly quiet place. About a dozen men dressed in what look like blue lab coats work intently at their benches.

“This factory has 35 employees in total,” said Oscar Hernández, who runs production. “In this place, we make and assemble mechanical and electromechanical clocks.” Mechanical clocks are powered by a weight or mainspring, while electromechanical clocks are powered by electricity or an electromagnet.

The people who work at Relojes Centenario are dedicated to clockmaking, and the majority have worked there for decades. Juan Gastón Olvera Uanzano, a production technician, has worked there for 38 years. “I entered when I was 22 years old,” he said with a hint of pride in his voice, “and now I am 60.”

He happily showed off a clock that he made on his own.

“I made and assembled all the pieces for this clock,” he explained. “It took me seven months to finish. It is my passion, this work.”

- The Museo de la Relojería is located at Nigromante No. 3 Col. Centro, just a few blocks from Zacatalán’s zócalo. It’s open Monday through Friday from 8:30 to 4:30 and Saturday from 8:30 to 12:30. It’s closed on Sundays. The entrance fee is a modest 10 pesos.

Joseph Sorrentino, a writer, photographer and author of the book San Gregorio Atlapulco: Cosmvisiones and of Stinky Island Tales: Some Stories from an Italian-American Childhood, is a regular contributor to Mexico News Daily. More examples of his photographs and links to other articles may be found at www.sorrentinophotography.com He currently lives in Chipilo, Puebla.