El Nevado de Colima, the sixth-highest mountain in Mexico, peaks at 4,260 meters above sea level. Although the word nevado means “snow-covered,” most of the year it’s not.

On top of that, it isn’t located in the state of Colima at all: it’s in Jalisco. But make no mistake, there is something special about El Nevado. First of all, it’s a volcano that has been extinct for thousands of years. It’s also the only high peak in Mexico that does not fall within the Mexico City–Puebla–Veracruz corridor.

But most importantly, it boasts such spectacular scenery that you will surely fall in love with it even if you are not a mountain climber and even if you reach nowhere near its peak.

If you are still reading this, it surely means that you are not an experienced mountain climber but quite possibly the sort of reader I would like to reach. Yes, my aim is to convince you to go visit El Nevado, but forget about trying to conquer the mountain’s highest summit.

So, let me begin by describing El Pico del Águila, the Eagle’s Peak. Although it is 3,909 meters high, is within easy reach of those of us without technical climbing skills.

A few years ago, members of Jalisco’s oldest hiking and camping club, Cuerpo de Exploradores del Occidente (the Western Explorers’ Corps), told me that they had given themselves a mission.

“We have to add four plaques honoring four of our fallen comrades to a monument we erected years ago high atop El Pico del Águila on the Nevado de Colima volcano. You’re welcome to join us, but you’ll have to carry a small bag of cement and a liter of water up to the top because the cross we put there has fallen over.”

When I told a friend that I was going to the Nevado de Colima National Park, he told me he had gone there several times in January and February, hoping to see snow.

“But Murphy’s Law prevailed and I never saw a single flake,” he said.

Well, my case was even worse: I had been in Mexico for 28 years and had never found snow on several visits to this volcano.

Considering I was going there on March 16, I certainly didn’t expect to see any on this occasion, but just as we were approaching the mountain, the clouds suddenly opened to reveal its peak. My compañeros’ eyes bulged. Never, they said, had they seen so much snow on El Nevado.

Unfortunately, the state of the paved road leading to the park entrance was abominable, full of so many potholes it looked as if it had been bombed.

“Don’t worry,” said my friends. “From here on up, the road is in perfect condition.”

And so it was. In fact, I’d say this dirt road inside the park is in such good shape that any car in tip-top mechanical condition will do fine here, although a Jeep would certainly be preferable.

Naturally, not all the vehicles in our party were in such shape, and soon two of them were steaming like fumaroles and had to go back down to visit a mechanic. The rest of us carried on and after about an hour and a half, we came to a big parking lot, the highest point on the mountain reachable by car.

“Now we hike straight up to El Pico del Águila,” my friends said.

Just as I’ve come to expect when hiking with members of this club, there was no trail to be seen anywhere.

We started slogging up the steep slope through a beautiful combination of snow and bunchgrass. After only 400 meters, we reached a ridge at an altitude of 3,890 meters and covered with several inches of soft snow. From here, we had a marvelous view of the mountain’s highest pinnacle, El Picacho Norte, which stands at 4,260 meters above sea level.

As the sun was now shining, we started making snowballs, taking pictures and, in no hurry, slowly making our way along the ridge for another 700 meters, right up to the top of the rocky peak.

Just as we were arriving, the weather suddenly changed, as it is wont to do at the top of high mountains. Dark clouds instantly filled the sky, a strong wind began to blow and suddenly it was snowing. Instead of groans, my Mexican companions broke out in cries of sheer delight, considering falling snow a blessing from on high.

In the distance, low clouds began to fog up the whole mountain. Meanwhile, the people in charge of restoring the monument were working feverishly, despite the cold. There was no way to know whether a full-blown snowstorm was about to be unleashed, and my mountain-savvy companions eventually decided to follow the dictates of prudence.

“Everybody get down off the peak,” shouted the group leader. “We’ll finish the job tomorrow. Let’s get out of here!”

So we did, and, wouldn’t you know, the fickle goddess of the mountain changed her mind 10 minutes later. The snowfall stopped, and out came the sun again. Time for more photos.

Upon reaching the cars, we drove down to a camping area called La Joya. Here there are lots of tall trees and large wooden cabins, inside of which campers pitch their tents to have shelter from the cold wind. There are also kiosks with tables, benches and barbecue pits.

But despite a roaring fire and all that extra protection for our tents, it was mighty cold that night. I was not the only one rubbing my feet to get them only somewhat warm even though I was using three sleeping bags, one inside the other.

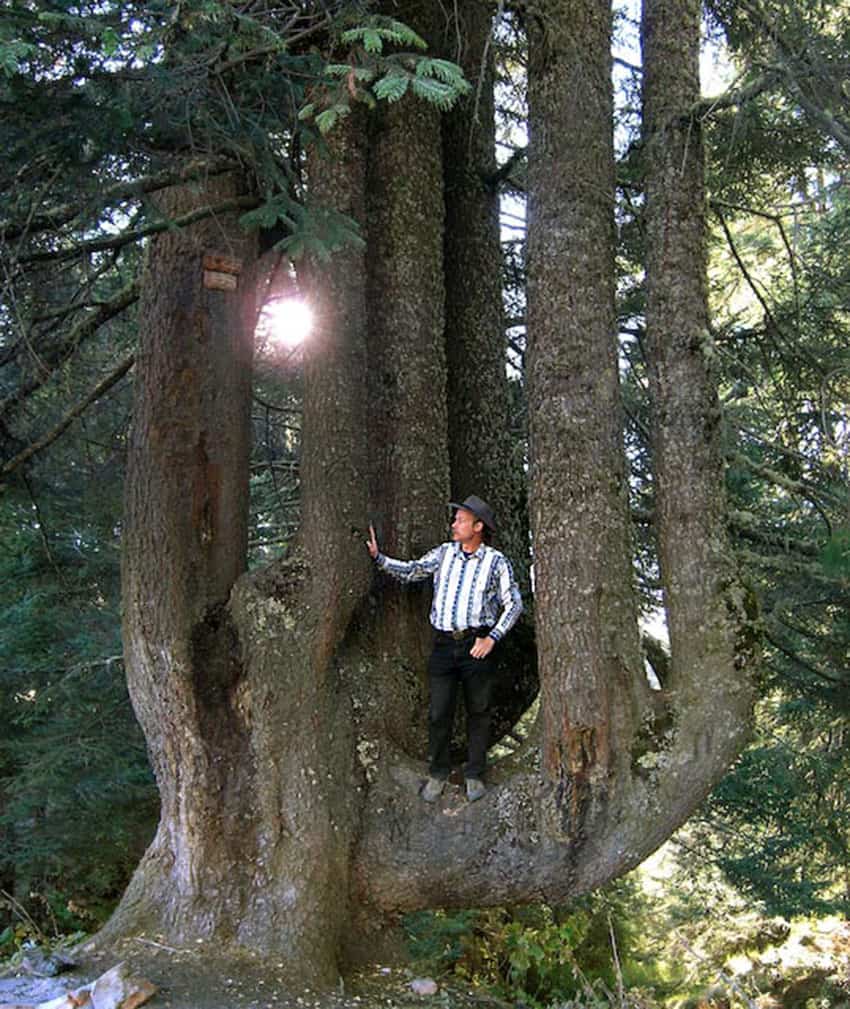

Now, you can avoid frozen toes by opting out of camping and just visiting the Nevado for a day trip. For example, there is a trail running through an aptly named place called Los Gigantes. Nowhere have I seen taller fir trees! Here you can see Abies colimensis, a species of tree described in 1989, so far considered unique to El Nevado. It’s also endangered due to illegal logging and climate change.

If you decide to do a hike upward, be careful to know your skills and limits. Not long ago, a group of experienced climbers on their way to El Nevado’s highest peak came upon a young man stressed out, dehydrated and separated from his group. His only guide was a Garmin GPS watch, which he had recently purchased and which, he had been told, would “get him to the top without a hitch.”

“How much further before I reach the blue triangle?” asked the exhausted hiker.

“Amigo,” said the group leader, “that little blue triangle is you!”

Sad to say, incidents of ill-prepared hikers meeting a grim fate on Mexican mountains are all too common. One of the most tragic occurred in February of 1968, when 11 young people died on Mexico’s third-highest peak, Iztaccíhuatl. As they were descending from the summit, a snowstorm — accompanied by thunder, lightning and strong winds — came up out of nowhere. The temperature plunged to -30 C. Unable to see and unprepared for such cold temperatures, the students froze to death only 350 meters from a refuge that would have saved their lives.

At present, El Nevado is open to visitors, but Covid-19 protocols are in effect and only four-wheel-drive vehicles are allowed. Before you go, be sure to check the park’s Facebook page.

If you decide to forget about reaching El Nevado’s summit and instead opt for the hike to el Pico del Águila (N19 35.337 W103 36.640), you’ll find the route here. The drive from Guadalajara to the highest parking spot on the mountain takes about 3 1/2 hours, while the hike is only two hours, round-trip. They say January and February are the months when you’re most likely to find snow. Good luck with that one!

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for 31 years, and is the author of “A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area” and co-author of “Outdoors in Western Mexico.” More of his writing can be found on his website.

[soliloquy id=”131591″]