They say that Mexicans have long memories. I am reminded of this idea at this time of year because that’s when the historic center, only a couple of kilometers from my apartment, becomes something of a fortress.

Today is October 2. For us foreigners, this is just another day, but for Mexicans, at least in Mexico City, it is emotional; this is the anniversary of the Tlatelolco Massacre.

In 1968, Mexico was getting ready to host the Olympics. It was the nation’s debutante ball, the first Olympic Games to be staged in Latin America and in a Spanish-speaking country. For the powers-that-be, it was their chance to show that Mexico was indeed a modern country, not just a land of poor farmers in big sombreros.

Millions upon millions of pesos were being spent on building state-of-the-art facilities and cleaning up Mexico City. To distract from what could not be fixed up, Mexico drew upon its impressive artistic talent, creating monumental sculptures, other artwork and one of the best public relations campaigns seen up until that time.

However, Mexico’s ruling PRI (Institutional Revolutionary Party) did not exactly succeed in its efforts.

Despite being democratic only at a very superficial level, the political party had enjoyed support from the popular, artistic and intellectual classes. This is because it was what emerged after the Mexican Revolution, and its dominance ended a century of war and chaos.

But with the memory of 19th-century chaos long-faded, Mexicans of the mid-20th century were focused on other challenges besides stability, such as promises from the 1917 Constitution (the current one) still unfulfilled.

The federal government of the time, however, had no interest in this, only the maintenance of its order.

There had been problems with unions and students since at least the 1950s, and the government was using increasingly authoritarian and even violent measures to contain the unrest.

It was particularly important to authorities to contain such forces while the eyes of the world would be on Mexico during the Olympics. There had been violence that summer in the city, with police attacking protests and even “invading” the public universities, which had a long tradition of autonomy from the federal government.

The Games channeled discontent not only because of all the money that had been spent but because it provided a tempting chance to be seen by the world. The government knew this as well.

And so, on October 2, 1968, just days before the opening of the Games, thousands of university and high school students decided to take advantage and hold a massive rally in Mexico City’s Tlatelolco neighborhood, at a square that represents the Mexican nation’s “Three Cultures” — indigenous, colonial and modern — with the architecture that surrounds it.

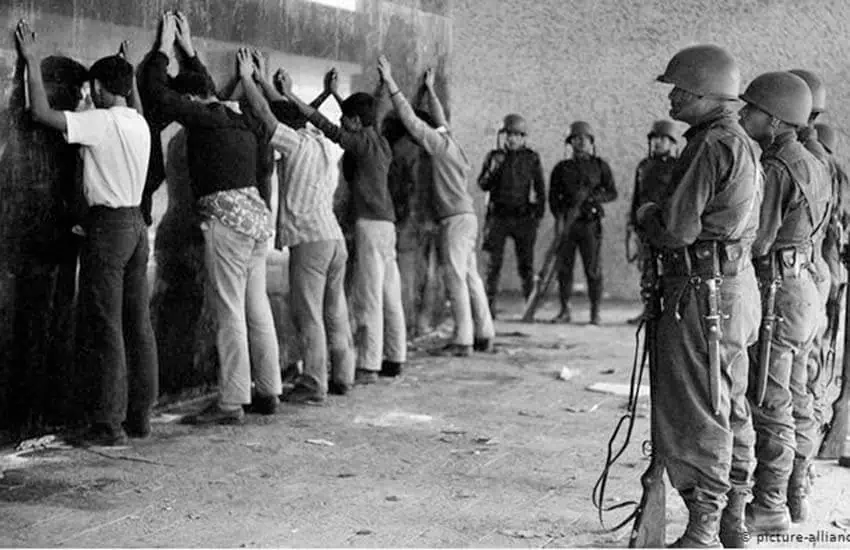

It would take thousands of words to describe what happened that day, and there is still fierce debate as to what exactly came to pass. The few things not in debate: there was military in the area, whose presence increased as the event went on; there were thousands of students and other activists in the square that did not end the rally despite the growing military presence; shooting started.

Mexican news media of the time dutifully reported the government’s line that the violence was started by the students and that the military simply got caught up in it. Blame has never officially been put on the military, but even before the emergence of new evidence in 2000, most believed, and still believe, that it was a coordinated military operation.

Even the number of dead from that day is highly contested, but the National Commision of Human Rights (CNDH) estimates the dead at over 300 on its website.

It wasn’t exactly an incident in the sense of the Kent State Massacre in the United States, which lasted only 13 seconds. Military actions went on into the night.

Overt political repression afterward lasted months and even years. “Foreign agitators,” especially foreigners who were teachers or professors, were blamed, forcing people like Helen Bickham, then an English teacher at the National Polytechnic Institute, to flee back to the United States for almost a year before she felt safe enough to return.

The Games went on as scheduled, but a very dark cloud had settled onto the sociopolitical situation in Mexico. The event not only soured the general public’s opinion of the PRI’s dominance but also shattered the confidence of the cultural and political elite who had actively supported the party for decades.

The PRI managed to keep power for over 30 more years, but it was a watershed moment; Mexico could not go back. There were later events that would further erode the PRI’s position, but only say the word “Tlatelolco,” and the mind goes automatically to the massacre, not the pre-Hispanic civilization that created the name nor the major loss of life there during the 1985 earthquake.

Finally, after years of ever-more-blatant vote-rigging, the PRI’s total hold on power collapsed in 2000. The memory of the massacre is such that with the election of Vicente Fox that year, a new investigation was ordered into the killings and the government’s role. New details emerged, but the main political actors did manage to escape judicial consequences.

The end of absolute one-party rule has not relegated the memory of October 2 to the history books. The PRI still exists and even elected a president in 2012. The Tlatelolco Massacre serves as an important symbol. For some, it is a focus for denouncing continued government repression and neglect. For others, perhaps, it is just to remind the government that they are watching.

More than 50 years later, these commemorations are still highly emotional and highly sympathetic even though many of the participants had not even been born yet in 1968. The chance of violence is always there, hence the steel barricades around major landmarks and shuttered businesses.

I also should mention that unless you are a Mexican citizen, you absolutely must not participate in any kind of activity related to Mexican politics; there are few quicker ways to get yourself deported.

I, personally, stay away from the historic center and Tlatelolco on this day, just to make sure I avoid any appearance of involvement.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 18 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.