Although most people outside Mexico believe Day of the Dead is celebrated only on November 1, Mexicans really celebrate “Days of the Dead.” The official days are November 1 and 2, but many places start celebrating as early as a week before with their own local traditions.

In many places, public altars created by the city, artists or local associations sit for days in downtown areas, and the sidewalks are often covered by intricate “carpets,” or tapestries, made of flowers, sawdust, colored sand or other temporary materials.

Huaquechula, Puebla, certainly has its altares monumentales, but it also has a unique tradition I’ve not seen elsewhere: the annual trueque.

A trueque is a market that dates back thousands of years, where people barter for goods. In Huaquechula, people come a few days before Day of Dead to a special trueque with one purpose: to barter for items to put on their altars.

I’d just entered the trueque when I saw Edith Vázquez and her family loaded down with pan de muerto, a Day of the Dead sweetbread that’s a staple on altars. “We traded peanuts and sugar cane for the bread,” Vázquez said.

They had three kinds of pan de muerto: round, with dough “bones” on top; muertito, in the shape of a small body and covered with red sugar; and rosquete, which Guillermina Rivera Silva said represents the face of the departed.

Although most of the breads were baked in gas ovens, Conrada Tapia baked hers in a brick oven, using firewood.

“Everything tastes better made that way,” she said, as she offered me a taste. Her breads had a delicious, smoky flavor.

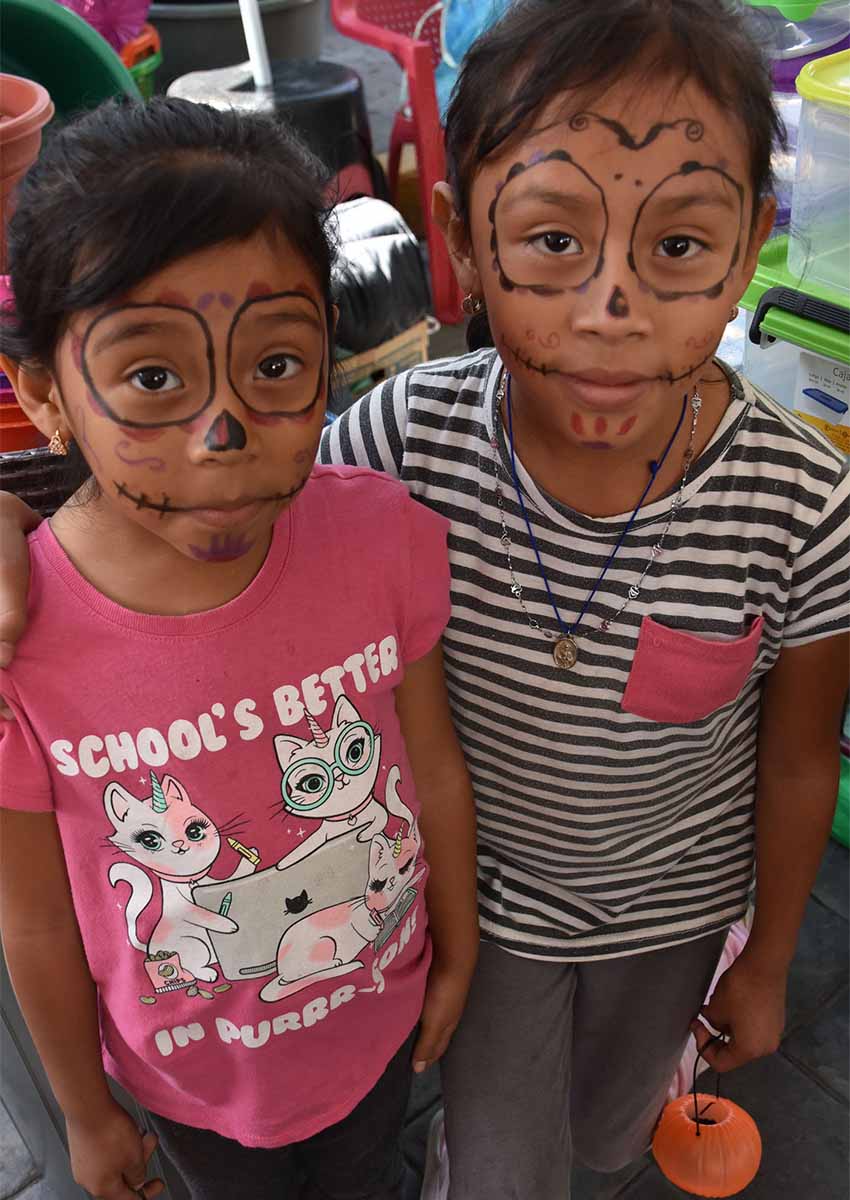

This year, the trueque was filled with people carrying and bartering for the various types of flores de muertos, especially the brilliantly colored cempasúchil (marigold) and terciopelo (cockscomb). Children wandered through with small baskets, seeking sweets or coins.

When asked which she preferred, nine-year-old Jade didn’t hesitate, saying, “Dinero.”

Karen Dominguez was one of the young people who, for a small tip, serve as guides and explain the town’s traditions.

“October 28 is when we remember people who have died in accidents,” she said. “The 31st is for children, Nov. 1 is for adults, and Nov. 2 is when we take flowers to the cemetery.”

Although she didn’t mention it, the 29th is for people who drowned and the 30th is for the souls of the forgotten.

This year, one street was filled with decorated graves. When I asked where I could get more information about them, I was pointed to Ana María Nevi Santivañez, who told me, “They are not real graves. They are symbolic, dedicated to people who worked on the festival.”

Some were humorous, especially the one for Señor Garcia, whose gravestone said he’d used a match to see if there was gas in his home.

Nevi and her granddaughter, Kendra Caltempan, were preparing meals for all the Day of the Dead festival’s participants, and had been since 6 a.m.

They said they’d be working until midnight, Caltempan said.

“We are cooking breakfast, lunch and dinner for 500 people. Tomorrow, we will prepare mole for 700,” she added.

Of course, this being Mexico, they invited me to try their chilaquiles and café de olla. How could I refuse?

Joseph Sorrentino, a writer, photographer and author of the book San Gregorio Atlapulco: Cosmvisiones and of Stinky Island Tales: Some Stories from an Italian-American Childhood, is a regular contributor to Mexico News Daily. More examples of his photographs and links to other articles may be found at www.sorrentinophotography.com He currently lives in Chipilo, Puebla.