Now that the pandemic’s finally easing, I’m traveling again, which means taking buses. I don’t have a car, and I’ve sworn that I will never drive in Mexico because, as a foreigner, I don’t know the informal laws governing how people drive.

I’m sure there are formal laws, but nobody follows them. Since I want to see my promised three score and 10 years, it seems best to let those who know how to navigate Mexico’s streets drive me.

For a frightening moment, I thought I’d have to get behind the wheel because my girlfriend, tired of chauffeuring me around Puebla, started to not-so-gently hint that I should do my share of the driving. I finally agreed that this was only fair, so she tested me in her car — a manual, of course. I hadn’t driven one in a couple of decades, but I was certain I hadn’t lost the knack.

But it quickly became clear that whatever knack I’d had was long gone. My ability, or lack thereof, to shift into any gear without putting the car into convulsions convinced her that playing chauffeur wasn’t such a burden after all.

So I’m spending more time in bus stations. In doing so, I find that I have a couple of burning philosophical questions: who the hell thought putting the bathrooms on the second floor in larger stations was a good idea and, to increase the weary traveler’s frustration, to make it mandatory that you have to pass through a too-narrow turnstile to use the facilities?

I know there are some kindly bus stations with their bathrooms on the first floor — a big shout-out to you, Querétaro — but the two terminals I frequent, TAPO in Mexico City and CAPU in Puebla, aren’t among them. Whoever decided to put bathrooms on the second floor has obviously never been in a bus station.

If they had, they’d notice that people carry these things called suitcases and that since many people are traveling long distances for vacations and whatnot, they often have more than one. Some are fairly large. Others are toting very large boxes. Lugging either of these up a flight of stairs is, at best, problematic, especially if you have an urgent need to use a bathroom.

In addition, designers would also notice (if they ever set foot in a bus terminal) that many people are traveling with children, making the climb upstairs doubly challenging. Watching a parent struggling with suitcases and a small child has convinced me that someone with a warped sense of humor, or a streak of sadism, made the decision about where to place bathrooms.

But the fun doesn’t stop with the ascent. Oh no! After you’ve finally made it to the top, you’re welcomed by a turnstile clearly patterned after a medieval torture device.

You must pay a modest fee to enter — five or six pesos — and fumbling for change with a full bladder adds to the excitement. Once you’ve paid, you hear a metallic click signaling that the turnstile’s unlocked. If you’re lucky enough to be traveling light and a person of modest size, you simply push one of the metal bars and pass through. You’re home free.

But if, like me, you’re not traveling light and you’re a larger-sized person, you’re in trouble.

When I’m traveling, I’m usually going to be away for several days or more. That means I’ll have at least one large suitcase. There’s simply not enough room for both of us to pass through the turnstile.

The first time I faced this situation, a cleaning woman happened to be standing just inside the bathroom. I asked her if she would watch my suitcase if I left it at the entrance. She nodded “yes,” and, of course, as I passed through, I watched as she disappeared into the ladies’ room. Happily, my suitcase was still there when I emerged.

When working on an article, I’ll have my camera bag and a backpack as well as the suitcase. I can’t pass through the turnstile with all of them. So, after several unsuccessful attempts to make it through in one pass with all my gear, I’ve come up with a simple system.

First, I pay for my suitcase and push it all the way through the turnstile. Moving it all the way through is critical. If I don’t, it gets stuck and neither me, nor anyone else, can get through. That’s more than a little embarrassing.

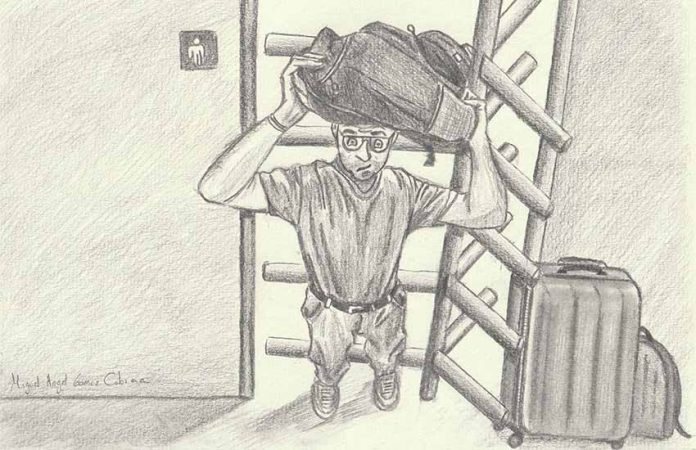

Once that’s accomplished, I put in more coins for my camera bag and push that through. Finally, it’s me and my backpack, although being larger than the tiny people the turnstiles are meant to accommodate, I have to hold the backpack over my head so I can squeeze through.

To make using bus station bathrooms a better, if not more pleasant, experience for you, here are a couple of important tips I’d like to pass along: first, don’t partake of fluids while waiting for your bus. I know that cup of coffee and Danish pastry are tempting while you wait several hours for the bus that you were told would leave at 11 a.m. but has been rescheduled to 4 p.m., but don’t give in; that’ll mean more visits to the bathroom, and you want to avoid as many of those as possible.

Second, pack light. Fewer suitcases mean an easier climb up the stairs.

Third, bring lots of change. The last thing you want to do is go racing downstairs for it while your suitcases sit lonely and unattended upstairs.

This system and these tips have been thoroughly tested and used successfully in many, many bus stations across Mexico. I urge you to try them.

No need to send me money. Really. Simply thinking that I may have helped a fellow traveler is thanks enough.

Joseph Sorrentino, a writer, photographer and author of the book San Gregorio Atlapulco: Cosmvisiones and of Stinky Island Tales: Some Stories from an Italian-American Childhood, is a regular contributor to Mexico News Daily. More examples of his photographs and links to other articles may be found at www.sorrentinophotography.com He currently lives in Chipilo, Puebla.