Around 7:00 p.m. on Good Friday, 14 young men, members of a group known as Los Varones, gather in the entrance of the Church of San Gregorio Magno. They stand in silence, encircling a casket that holds a statue of the crucified Christ.

They’ve been up since before dawn, only having slept a few hours, and have already participated in hours-long processions through San Gregorio Atlapulco, a pueblo in Mexico City. They’ve been fasting since Wednesday night.

The group will soon begin the Silent Procession, in which they carry the casket, which weighs about 250 pounds. The procession lasts almost seven hours. They’ll walk barefoot.

Octavio Flores worried as he waited.

“I worry because we walk far; we carry the heavy tomb with Jesus,” he said. “But I’m also happy because it is something unique in my life, something incomparable, a joy. It is difficult physically but not mentally because I have faith.”

The name Los Varones comes from the Franciscan missionaries who are also called Los Santos Varones (varón usually translates as “young man,” but here it refers to someone who’s chaste). It’s believed that the Franciscans began to organize young men into the group that exists today back in the early 17th century. The group in San Gregorio appears to be the only one of its kind in the world.

While Los Varones perform various tasks during the year, their main work happens during Holy Week, when they organize virtually all the events to mark the religious days. But demands are put on them well before that week: they prepare physically for months since they’ll be carrying heavy statues for hours during processions.

“We will carry a heavy table, run, do pushups,” said Flores. “We will put another person on our back and climb stairs.” They also prepare spiritually, attending more Masses.

There are more challenges during cuaresma, a period which for these young men lasts from Ash Wednesday until Easter Sunday, or 53 days.

“You cannot have contact with your girlfriend,” said Alberto Casas García, the group’s leader. “You cannot smoke, drink alcohol, dance or go to fiestas.”

Ricardo Castro, who’s been a varón for two years, admitted, “Those days, yes, it is hard because you have to be in the church. There is so much work for us. For me, the challenge is my relationship with my girlfriend, but she is very understanding.”

On Palm Sunday, two varones carry the statue of Jesus astride a donkey through the pueblo, trailed by the other members of the group, as well as 12 boys dressed as Apostles and a few hundred people. After the palms are blessed by the priest, the procession heads to the home of the síndico, where a meal is provided for over 100 guests. The síndico, which roughly translates to administrator, also provides the meal for the Last Supper.

“My family helps, but it is my responsibility to organize everything,” said Uriel Avelino Ávalos, who was the síndico in 2019. “I waited eight years. I want to do it for the church, for God.”

On Wednesday, the church altars are decorated with fruit, some of it tied together with rope. “The fruit represent the tears of the Virgin, which becomes food for the people,” said Javier Márquez Juárez, who has written about ceremonies in San Gregorio. “Altars with fruit are only found in San Gregorio, not other pueblos.”

On Holy Thursday, the 12 boys representing the Apostles sit at long tables for the reenactment of the Last Supper. They’re served soup, fish, chile relleno and rice. Los Varones, who are fasting, stand nearby while other people enjoy bread and atole (a hot drink made from corn) provided by the síndico.

After the meal, the priest washes the feet of the Apostles, trailed by the síndico, who places a crown of thorns on each Apostle’s head and hands them a coin. “This represents the money that was given to Judas,” Avelino said.

The silent procession begins as night falls. A white cloth covers the eyes of the statue called Padre Jesús. “This represents the fact that Jesus will soon die,” said Castro.

The statue is carried east while the Virgen de Doloroso (Virgin of Sorrow) statue heads west.

“In this way, Christ represents the sun and Mary the moon,” said Márquez. “They will meet … and return together to the church.” When they meet, the figure’s handkerchief is removed, “so Jesus can see his mother,” said Castro.

Then early in the morning on Good Friday, Los Varones place a large wooden cross on Padre Jesús and carry the statue through the pueblo, making stops at the the town’s 14 chapels. They’re accompanied by singers, who perform alabanzas, slow, mournful songs. At each chapel, the procession walks on tapetes de aserrín, which are beautiful designs made from colored sawdust that people have spent hours creating.

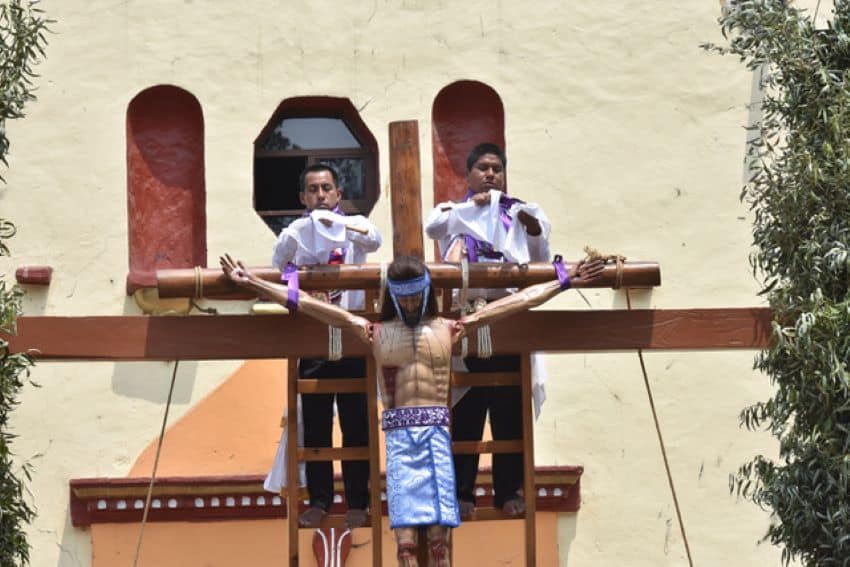

In the mid-afternoon, Los Varones exit the church dressed in white shirts — signifying purity — and black pants, which signify sorrow and death. They walk barefoot, lining up in front of the crosses holding Jesus and the two thieves who were crucified with him. On either side sit two young women, who must be single and childless, representing Mary Magdalene and St. Veronica. Two varones climb ladders to the top of the cross holding the Christ figure.

“The steps of the ladder hurt your feet,” said Ricardo Serralde. “There is the sun. But with devotion, you forget all that.”

They slowly remove the crown, nails and Christ figure using white handkerchiefs. “We are not allowed to touch the figure with our hands because we are not pure,” said Castro. It takes over an hour to lower the figure, which is placed in a coffin covered with red rose petals.

The final procession begins at 7:00 pm, the coffin carried by six, sometimes eight, of Los Varones. As the procession moves through the pueblo, they’ll climb steep stairs or inclines, stopping again at the chapels, where neighbors provide bread and atole to the crowd. But it’s not until they reach the Calvario Chapel that the men finally take some sustenance, each drinking a glass or two of orange juice.

The Fuego Nuevo (New Fire) is lit just before midnight on Saturday. The síndico lights a large candle from it, and then people light their candles off his. Then, all lights and candles are extinguished and a Mass is held. Then the candles are relit as the church bell rings, a conch shell is sounded and traditional Aztec drums are beaten.

On Sunday morning, Los Varones distribute holy water containing rose petals that had adorned Christ’s coffin and hand out chamomile. The fruit that decorated the altars is passed out. The mood is festive and Los Varones, who have slept no more than 10 hours over three days, look alert and happy.

When asked how they can do what they do during Holy Week, every member talked about his faith. But one wordless gesture by Ricardo Castro perhaps explained it best. We were in a chapel around 1:00 a.m. after the Good Friday procession. Castro made eye contact and raised his head as if to ask, “What do you think?” All I could say was “incredible.”

He smiled and pointed one finger heavenward.

Joseph Sorrentino, a writer, photographer and author of the book San Gregorio Atlapulco: Cosmvisiones, is a regular contributor to Mexico News Daily. More examples of his photographs and links to other articles may be found at www.sorrentinophotography.com He currently lives in Chipilo, Puebla.