She had the most fashionable hotel in all of Cuernavaca in the early 1900s, but then lost it all in a whirlwind of violence, running for her life.

Rosa Eleanor King was born in Karachi in 1865 to a tea plantation family during the British Empire. These beginnings did not suggest that she would be a witness to the Mexican Revolution, but she got an up-close-and-personal view of it as the fighting came to Cuernavaca. She even hosted the Revolution’s military leaders and high-level political figures in her hotel.

As an adult, she first immigrated to the United States, where she met and married Norman Robson King. From there, the couple traveled to Mexico and both fell in love with it, visiting various times, then moving to Mexico City. In 1905, they visited Cuernavaca, but it did not quite strike their fancy.

In August of 1907, Norman died suddenly, leaving behind Rosa and their two small children. Rather than return to England, King built a new life in Mexico, returning to Cuernavaca. She arrived during the rainy season, when everything was lush and green, improving her opinion of the place.

Prior to this, she had never worked, never mind run a business, but she did understand the expat community and others in the leisure class in Mexico.

She rented an old grocery store and turned it into an English-style teahouse, a place for foreigners and upper-class Mexicans to pass the time. She added what she called a “curiosity shop,” filled with local handcrafts, especially ceramics. To keep it filled, she started a ceramic workshop in a nearby indigenous community.

By 1909, the businesses were doing well enough for her to take the Morelos governor’s suggestion that she buy and remodel the Bella Vista Hotel in the center of Cuernavaca. Her modern update of the hotel opened in June of 1910, right as she was hearing rumblings of the activities of revolutionary Emiliano Zapata.

She was well aware of the poverty of the countryside and the hard life of the peasants and sympathized with them. But she had trouble believing that Zapata’s efforts would amount to more than any of the other uprisings in Mexico before him.

Zapata did enter Cuernavaca to meet with new president Francisco I. Madero after previous president Porfirio Díaz had been ousted after more than 30 years in office. Zapata assured King of her and her hotel’s safety, and he kept that promise.

The hotel weathered the initial storm of the Mexican Revolution, even as King’s wealthy patrons fled. Politicians and military leaders from various factions of the revolution took their place.

But then this changed with the coming of a counter-coup against Madero that brought Victoriano Huerta to power. The various rebel factions, including the Zapatistas, were incensed. Fighting escalated.

Rosa still hoped to save her hotel, but warfare destroyed the railroad connection to Mexico City and the Zapatistas had laid siege to Cuernavaca.

When federal troops decided that they could no longer hold it, King went with the last column of soldiers out of the city, fleeing into the mountains. This is the climax and by far the bloodiest part of the story, as the Zapatistas began to pick off members of the caravan. Of 8,000 people, only 2,000 made it to safety, but Rosa was one of them.

This tale is chronicled in her book, Tempest Over Mexico, published in 1935. It also tells the story of her experiences through the rest of the war, when she lived in Mexico City, then Veracruz.

She returned to Cuernavaca after the Zapatistas were driven out in 1916, only to find that there was no way to rebuild in a city that was all but destroyed. Later, her property was declared abandoned, and she lost the title to it.

After the fighting was completely over, her children settled in Mexico City, but Rosa decided to return to Cuernavaca.

There was no hope for the hotel, nor for any other kind of business for King due to her health, but she felt she belonged there and stayed in Cuernavaca until her death in 1955.

What strikes me while reading her book, especially near the end, is how Rosa came to terms with all this.

Several times during the story, she talks about feeling that she wasn’t or shouldn’t have been affected by the Revolution because she was a foreigner. But by the end of the memoir, she discards this notion, deciding that she was a worm in a furrow that the farmer would not stop for (her analogy).

Despite losing everything — and almost her life — King expressed no bitterness at her fate nor anger at Zapata. The Revolution was inevitable, she said, considering conditions for the poor at the time.

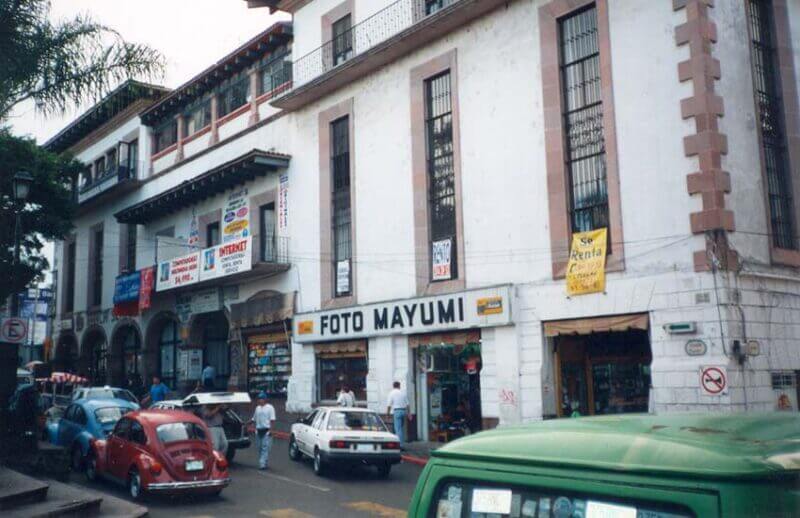

The hotel was rebuilt and still exists by the city’s Juárez garden but now houses a number of shops.

In the 1950s, King was offered US $100,000 for the movie rights to her book, a fortune in those days. She turned it down because they wanted to make changes to the story.

This would be a problem later for her family as a later attempt to make a Hollywood movie stumbled over the same problem: great-grandson Phillip Barnett believes that one problem for would-be moviemakers is that King’s story has no love interest.

“It is not enough that she was a strong woman surviving an impossible circumstance,” he says.

Rosa’s initial descendants stayed in Mexico, but over the generations they have migrated north. Boarding school in Canada had much to do with this as various generations got their education there, made contacts and settled down.

Most are descended from Rosa’s daughter Vera, with last names such as Barnett, Pantalone and Dawe.

Few are left in Mexico, but Mexico is part of the family’s identity, and one member even decided to return to the land of his grandmother.

Phillip Barnett was raised north of the border but calls himself a rebel and returned south.

Perhaps it is more accurate to say that he inherited that aspect of Rosa’s personality that could not be happy anywhere else.

To read Rosa King’s story, download a free digital copy of Tempest Over Mexico in either EPUB or PDF format at its website.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 18 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.