The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) has called for Mexico to develop a comprehensive national forensic policy to help confront the crisis of disappearances in the country.

IACHR vice-president and rapporteur for Mexico, Esmeralda Arosemena de Troitiño, made the statement during a public hearing on Thursday. The hearing was held in Los Angeles, California and attended by Mexican representatives and led by national search commissioner Karla Quintana.

Arosemena acknowledged the government had made efforts to tackle the disappearance crisis, but said more effective coordination between institutions was needed to address the estimated 52,000 unidentified bodies in the country.

“A national public policy that has this concept of responsibility for the articulation, for the coordination, the strengthening of the institutions themselves, endowed with resources, is indispensable,” she said.

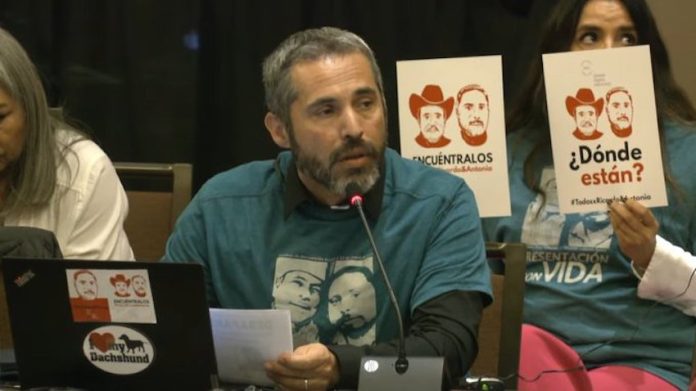

The hearing was also attended by families of the missing, including relatives of lawyer Ricardo Lagunes and indigenous leader Antonio Díaz, who disappeared between Michoacán and Coahuila on Jan. 15, and the mother of Víctor Adrián Rodríguez Moreno, who disappeared in Coahuila during 2009.

Families of the disappeared said they felt abandoned by the Mexican government. They criticized “institutional inefficiency,” particularly in cases involving migrants which required coordination with other countries. They also complained that families had been shut out of relevant legislative processes since Dec. 2021.

“If families do not participate, this [comprehensive policy] will not be achieved either, because they are that internal engine of not only the feeling but the need for truth and justice,” Arosemena agreed.

For their part, the Mexican delegation pointed to advances such as the creation of the Extraordinary Forensic Identification Mechanism and the National Forensic Data Bank (BNDF). Representatives of the Attorney General’s Office (FGR) said this national database of forensic information already hosts the records of more than 15,100 missing persons and 8,000 bodies that are yet to be identified.

“Thanks to this tool we now have a record of 616 clandestine graves from which 1,264 bodies have been recovered,” said Joaquín Torres, general director of the FGR’s Special Prosecutor’s Office for Human Rights.

However, the human rights organization Centro Prodh questioned Torres’ claim that the BNDF was already in operation. Instead, the NGO said that the Mexican Attorney General’s Office (FGR) has litigated against families who demand its implementation.

The BNDF was established in 2017 through the General Law on the Disappearance of Persons, which stated that the database should be ready by 2019. By 2022 it was still not operational, and several court cases brought by relatives of the disappeared found the FGR was remiss in allowing the delay. The FGR has appealed the decisions.

Mexico’s National Database of Missing and Unlocated Persons (RNPDNO) currently lists more than 112,000 disappeared people in Mexico. The figure has climbed steadily over the last 20 years, particularly since around 2016.

At the hearing, Centro Prodh stressed that the families’ testimony “shows that disappearances are not yesterday’s inheritance but today’s sad reality.”

With reports from Latinus, La Jornada and Infobae