Many years ago, I saw a short video. It was supposed to be funny in that clever “hindsight is 20/20” way. In it, two boys who would today be in their 70s sit by a stream of clear running water. One of them dips a bottle into it and says, “One day, I’m going to sell this water to people in bottles.” The other boy looks at his friend like he’s crazy. “But water’s free. Who would ever buy water in a bottle?” he says incredulously.

Who, indeed.

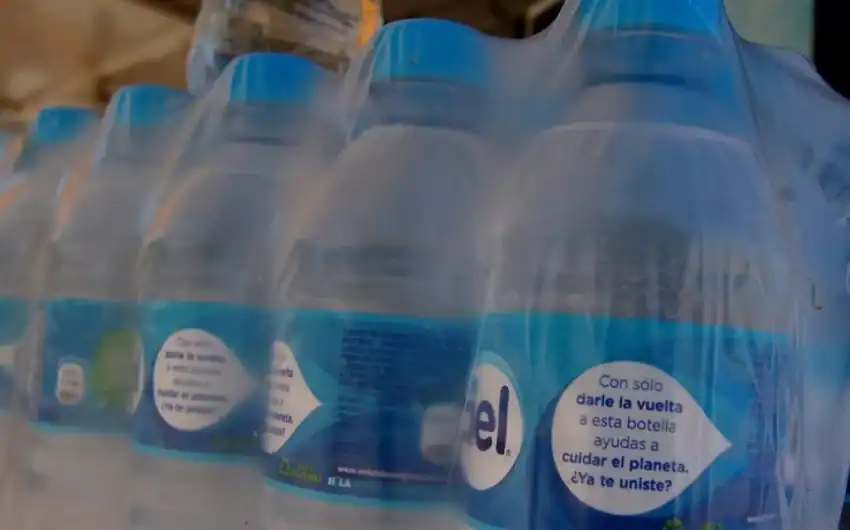

Well, here we are, all buying water in bottles. Its market share worldwide is now at nearly US $350 billion. But it’s sure worth thinking about alternatives to this reality. Wouldn’t it be something if we could go back to saying, “Water in a bottle, for money? But it falls from the sky and gathers on and below the ground for free!”

The reality of water in Mexico

The reality is, of course, that water is not free. And even when we’re prepared to pay for it, it’s not necessarily forthcoming. In Xalapa, where I live, tandas de agua (water rationing schedules) have been a thing for years now. Doing too much laundry on the wrong day or accidentally leaving a toilet running for a few hours means you could be out of luck for a few days afterward.

If you were here in the spring of 2024, you might remember some scary potential scenarios. Talk of “Day Zero” — the day that Mexico City would officially run out of water — was everywhere.

And yet, there were certain entities in Mexico who, curiously, never seemed to run out of water, even as the communities surrounding them rationed. For several weeks that spring, I personally remember a scarcity of even bottled water and garrafones. Curiously, there was no shortage of Coca-Cola and other sodas: those were stocked up as usual.

In the very-worth-reading report “Los Millonarios de Agua“ (“Water Millionaires”), authors Wilfrido A. Gómez Arias and Andrea Moctezuma point out a perhaps unsurprising fact: 3,304 “water millionaires” (1.1% of users) use 22.3% of all the water available in Mexico.

Wow.

A new water law in Mexico

Water is the important resource, of course. Whoever controls it literally controls everything. It even surpasses money in importance: money might be an important resource, but money is just a symbol. Water is a resource we cannot live without.

Now, we’ve got a new water law that’s caused quite a bit of uproar, specifically among farmers. It’s meant as an antidote to correct a President Salinas-era law, circa 1992, that essentially privatized water concessions. This allowed individuals and institutions to basically administer their own water from national territory with no involvement from water authorities at all. From there, they could basically do whatever they wanted in terms of access to their allotted amount of water…even sell it. This new law is an attempt to rein that in. It’s not a good look, after all, when everyone is rationing except a select, very wealthy few.

Farmers have fought the law, saying it will impede them from selling or passing on their land to their children. The government, for its part, has assured them that they will still be able to do so. The only circumstance in which they’d have to get a new concession would be if the use of the water changes.

Who gets access to water and who doesn’t?

My main question about the law is this: Are the water millionaires, accounting for about 1% of companies and individuals, still going to be able to extract over one-fifth of the country’s water?

Will resort pools and golf courses stay full and green while the surrounding areas continue to ration? From what I can tell, most likely. Concessions won’t be able to be transferred to others without state involvement. Fine. Is Coca-Cola or Nestlé going to be trying to transfer their concessions? My guess is no.

And if that’s true, then how exactly does this law guarantee water as a human right? It’s not that it causes harm — it’s that it doesn’t seem to really do anything to change the status quo. We’ll still be paying for water. We’ll still be rationing while the big players continue to use their concessions.

‘One water, one law’

So what does it mean exactly for water to be seen as a “human right” rather than a “good”?

I’m with the “One Water, One Law” crowd on this one. “The law they’re proposing is a simulation,” said María González Valencia, director of the Mexican Institute for Community Development (IMDEC). “It keeps the old privatizing structure intact and treats water as a market, not a human right.”

Well, exactly. If they can still extract water and sell it back to us while we ration, what exactly is changing? And will heavier state involvement in water concessions be an area in which Mexico is magically not corrupt? I know that sounds cynical, but it’s an honest question: What’s the plan for making sure this all goes down like it’s supposed to?

I’m glad, though, that they’re at least trying to deal with the issue. It needs to be dealt with — it’s literally a matter of life or death.

How much further could they go? “One Water, One Law” advocates have some good ideas: “Participants demanded publication of a full list of concession-holders delinquent on their fees and urged that new permits be conditioned on sustainable use,” wrote the author of an article on the movement, Tracy L. Barnett, in MND. “Others proposed regional water councils with citizen participation to monitor local supply, and mandatory rain-harvesting systems for public buildings to reduce pumping from Lake Chapala.”

And here’s an idea, surely shared by many, that I’ve hoped for for a long time now. We don’t all have access to wells, but it rains on us all at least sometimes. Water catchment and purifying systems — Mexican-grown! — already exist. If the government were to subsidize the installation of those systems in homes and buildings around the country, that could ensure an important lifeline.

Wouldn’t it be something if Mexico became a model around the world for its handling of water for a growing population?

Trying to rein in some of these big guys by cutting off the possibility of treating water as a commodity without government oversight is a start.

But let’s take this all the way; there’s so much more we could do.

Sarah DeVries is a writer and translator based in Xalapa, Veracruz. She can be reached through her website, sarahedevries.substack.com.