We’ve already talked about how the debate between free trade vs. fair trade sits at the core of President Trump’s policy agenda.

It’s a wide and complex discussion — covering deficits, tariffs, international institutions, subsidies, dumping and plenty of other trade-related issues. For this piece, I want to focus on trade deficits because they are the real driving force behind Trump’s commercial instincts. Of all the texts in this series, this one probably brings out my inner David Ricardo the most. I’ll try to keep it digestible.

Over the past decade — especially the last eight years — the U.S.-Mexico trade relationship has intensified like never before. As most of you already know, Mexico and the United States are now each other’s top trading partners, both in exports and imports. Mexico is the largest buyer and seller for the U.S., and vice versa. But given the difference in economic size — roughly 16 to 1 (U.S.: ~$30 trillion vs. Mexico: ~$1.86 trillion) — and Mexico’s export-oriented model, Mexico naturally exports more than it imports. That dynamic has deepened Mexico’s trade surplus with the United States.

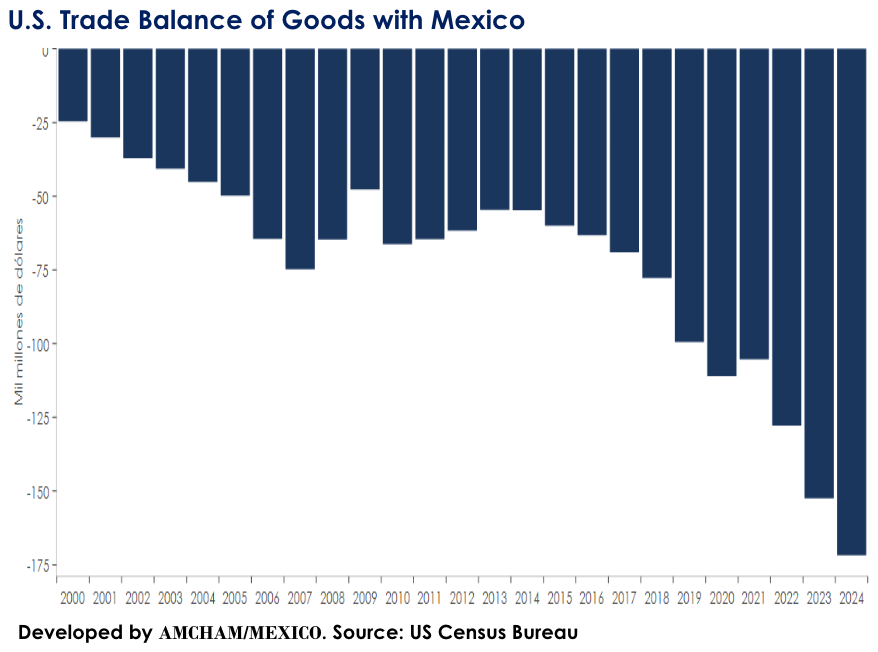

When Trump first took office, the U.S. trade deficit with Mexico stood at around US $63 billion. By the end of 2024, it had grown roughly 2.7x, reaching $171 billion. Well, well, well — that sounds like terrible news for Mexico with Trump back in office. And yes, it could be bad news. But only if we keep measuring trade deficits the wrong way.

(Picture me rolling up my sleeves — here comes the fun part.)

Why isn’t it enough to measure trade balances simply by adding and subtracting goods crossing borders?

Imagine you have a “trade relationship” with two entities. One is a car mechanic down the street; the other is a convenience store on the other side of town. Sadly for you, you run a $100 deficit with each. But here’s the twist: you’re also a car mechanic. Last week, you sold $900 worth of parts and oil to the nearby mechanic, and she sold you $1,000 worth of inputs you needed to keep your business running. That’s a $100 deficit. Meanwhile, you buy $100 worth of goods from the faraway convenience store — and sell them nothing. Same deficit. Completely different relationship. Right?

Now, let’s rename the characters. You are the United States. Closest-car-mechanic is Mexico. Faraway-convenience-store is China.

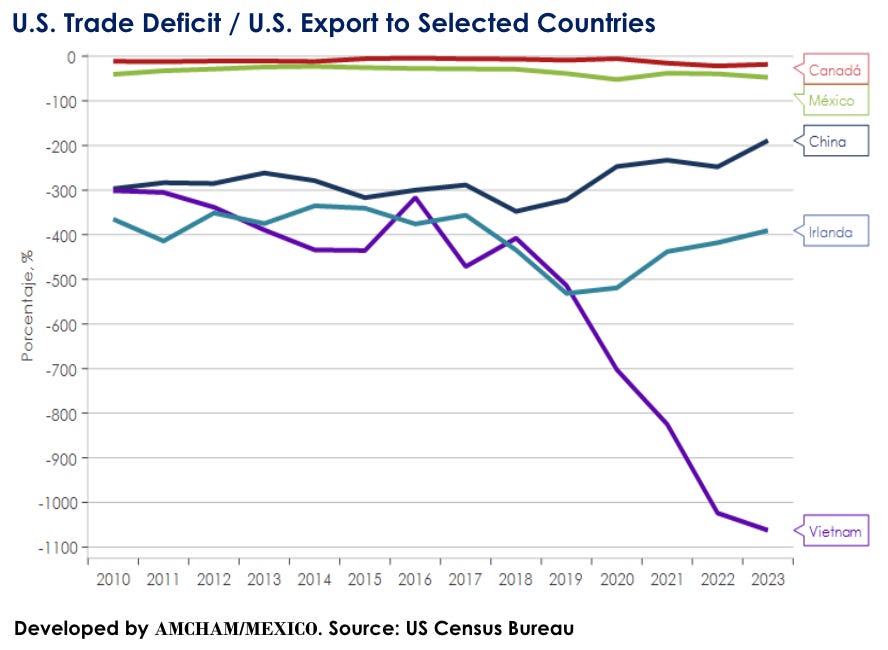

One way to assess trade relationships more intelligently is to look at trade deficits relative to exports. By 2024, the U.S.-China relationship showed a deep structural imbalance, with a deficit equivalent to -205.8% of U.S. exports to China. With Mexico, the figure is far more balanced, around -51.4% over time. In plain English: the U.S. trade deficit with Mexico rises and falls roughly in line with U.S. exports to Mexico. With China, the U.S. mainly imports finished goods and sells comparatively little in return.

There’s another way to look at this. We can adjust the traditional trade balance by subtracting the exports to the U.S. that are produced by U.S. companies operating in Mexico.

In 2023, Mexico exported about $560 billion to the United States. Roughly $220 billion came from manufacturing and export services. Of that amount, 80% originated from U.S.-owned firms, about $176 billion. That same year, the U.S. recorded a $152 billion trade deficit with Mexico. By this logic, you could argue that the “real” balance wasn’t negative at all. Interesting, right? That said, this approach is still imperfect, since those exports also contain non-U.S. components.

Which brings us to the last mile of the text: components and value added.

To truly understand trade relationships, we must measure them in terms of value-added content. Back to Closest-car-mechanic. If she sells me an engine for $100, that’s the headline number. But what if 75% of that engine’s components were initially produced by me and sold to her? Suddenly, the deficit looks very different — because we’re co-producing the engine.

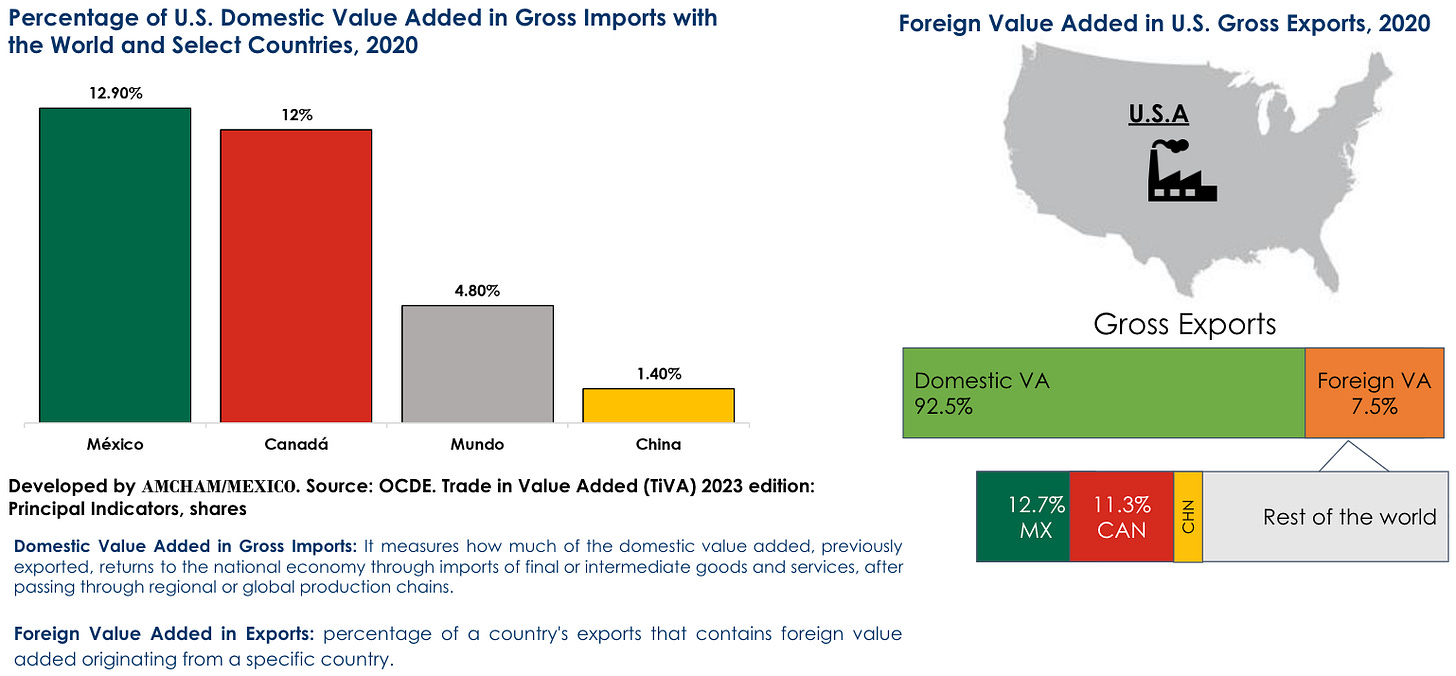

This is precisely what happens between the United States and Mexico. Mexico has the highest share of U.S. components embedded in its exports — roughly 10 times more American content than Chinese exports and nearly three times the global average. And it works the other way too: among all foreign value added in U.S. exports, Mexico ranks first, accounting for about 13%.

And, keeping the car analogy, the auto industry works exactly like that: the U.S.-Mexico automotive trade deficit appears large in gross terms ($108 billion), yet, when measured in value-added terms, it reduces by 82% ($19.8 billion)!

I promised short essays, and I’ll keep my word. So let’s end with some cool and sexy takeaways. Not all trade deficits are created equal — and we shouldn’t treat them as if they were.

The U.S.-Mexico economic relationship has evolved from a traditional buyer–seller dynamic into a deeply integrated co-production system.

That system is like a scrambled egg. You can’t separate the yolk from the whites and put them back in the shell. The only sensible thing to do is keep scrambling — maybe add some bacon, cheese and more eggs — and make it even better. Cheers!

Pedro Casas Alatriste is the Executive Vice President and CEO of the American Chamber of Commerce of Mexico (AmCham). Previously, he has been the Director of Research and Public Policy at the US-Mexico Foundation in Washington, D.C. and the Coordinator of International Affairs at the Business Coordinating Council (CCE). He has also served as a consultant to the Inter-American Development Bank.