By this time around, you should be asking yourselves: Well… and when is this guy going to write about the flagship industry of the region? The time has come, so let’s talk about the auto industry.

I find this industry fascinating. It’s full of mysticism, culture, myths, half-truths, misunderstandings — and an impressive ability to trigger political debates.

Because of that, I do have to emphasize that I’m not an auto-industry expert. So, to all my friends out there who are: you are more than welcome to correct me publicly if I say something misleading.

Now, let’s start with a couple of fun facts and interactive questions to guide this conversation.

First: if I asked you, what is the average age of a new car buyer in the United States? What would you think it is? (Literally, pause for a few seconds.) Most people guess 30-something.

Reality check: it’s about 53 years old. Think about what that implies.

Second: what would you guess is the trend in global demand for cars? Rising? Falling? Considering that the world’s population keeps growing and poverty has generally been declining, you’d think demand would be skyrocketing. But global vehicle sales have been surprisingly… flat-ish.

Over the last decade, the world has moved from the mid-80 millions to the high-80 millions in annual light-vehicle sales — growth, yes, but nowhere near “explosion.” In other words: the market isn’t expanding enough to let everyone win comfortably, as we used to.

So what happens when demand stagnates, the buyer gets older, tech changes everything (EVs + software), and costs keep rising? You get a global knife fight over market share. And that’s where China enters — big time.

China isn’t just “making more cars.” It’s pushing exports hard, especially as competition intensifies at home. In 2023, China became the world’s largest car exporter, surpassing Japan, and has maintained that position into 2024 and 2025. The strategic point isn’t just volume — it’s price and scale. China can flood markets with lower-cost vehicles and components, and that puts pressure on everyone: the U.S., Europe, Japan, Korea… and yes, Mexico. In a world where the pie isn’t growing fast, the player with scale and cost advantages can start eating other people’s lunch.

Now here’s the part that matters for this series: North America does not compete with China as three separate countries. We compete as one production system — or we don’t compete at all.

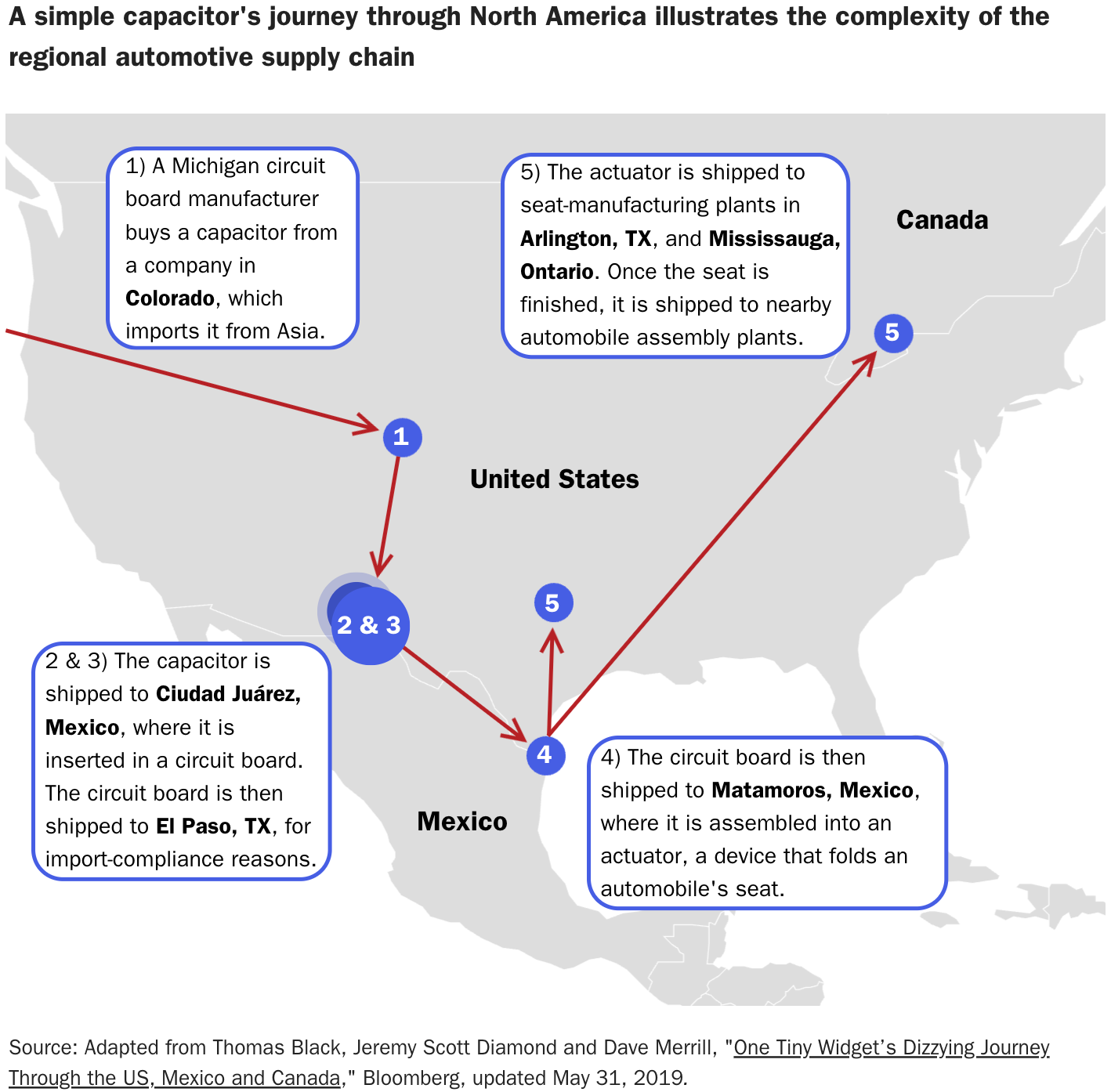

A car is not “made in one place.”

In North America, it’s assembled through a supply chain that zig-zags across borders. Some components can cross borders as many as eight times before becoming a finished vehicle. That’s not a bug in the system. That is the system.

This is also why the “Mexico exports cars to the U.S., therefore Mexico is stealing jobs” argument is — at best — incomplete.

The deeper reality is that regional production supports regional jobs. One estimate in the material I reviewed puts total automotive employment across the three countries at 5.1 million, with 7 out of 10 jobs located in the U.S. The U.S.-Mexico auto relationship isn’t a normal buyer-seller relationship. It’s co-production.

That’s not just a nice sentiment or a sexy slogan. It changes the economics.

Here’s a key example: Mexico is the #1 destination for U.S. auto parts exports. In 2024, Mexico imported US $72.2 billion in auto parts from the United States — about 31% of total U.S. auto parts exports worldwide. That means when Mexico produces and exports vehicles, a huge amount of that value is actually pulling demand for U.S.-made components, machinery, engineering, design, logistics and services.

And this is where we get to the trade deficit debate (yes, again — because it always comes back).

On a gross basis, the bilateral auto trade deficit can look enormous. But when you measure trade the way grown-ups should measure production — by value added — the story changes dramatically. One analysis I’m using here shows a gross U.S. deficit with Mexico in the auto industry of $108.9 billion (July 2024–June 2025), but only $19.8 billion when measured in value-added terms — an 82% reduction!

That’s the whole point: in a co-production system, gross flows exaggerate imbalances because they count the same value multiple times as it crosses borders. Value-added measurement asks the better question: who actually contributed what to the final product?

Now, zoom out: if North America is this integrated, why does China matter so much?

Because when you buy a vehicle or component from a tightly integrated regional partner, it activates your own upstream network. When you buy it from far away, it just doesn’t. Today, imports to the U.S. from Asia or Europe face the same baseline tariff treatment, which is lower than tariffs imposed on Mexico. Still, they don’t generate North American integration — and therefore represent a greater loss to regional (and obviously, American) production networks.

So the strategic thesis is simple (yeah, right):

- The global market is getting tougher (slow growth, shifting demand, massive tech transition).

- Consumer patterns are changing alongside generational transition.

- China is pushing hard with scale and price.

- North America’s best response is not to argue about who “wins” inside the region.

- It’s to build a more competitive regional platform — faster, cheaper, more resilient and more innovative than the alternatives.

That also means being honest about the risks of fragmentation. The same value-added analysis highlights that a hypothetical “move everything to the U.S.” scenario would create serious ripple effects — like reduced supplier output in Mexico, reduced U.S. exports to those suppliers, and knock-on effects across other integrated sectors. In plain English: breaking the system doesn’t magically recreate it somewhere else. It will just break it (both for Mexico and the United States).

Let me land this with one last, practical point: Mexico’s auto engine is already running at scale.

Through November 2025, Mexico produced 3.7 million light vehicles and exported 3.1 million; 80% of those were exported to the U.S. That capacity is not a side dish — it’s one of the main ways North America stays relevant in a brutal global arena.

So yes: the auto industry is the flagship. But the flag it carries isn’t “Mexico vs. the U.S.” It’s “North America vs. the rest.”

And in a world where China is increasingly playing offense, the only smart strategy is to stop treating our region like three separate garages — and start treating it like what it already is: one shared assembly line.

Pedro Casas Alatriste is the Executive Vice President and CEO of the American Chamber of Commerce of Mexico (AmCham). Previously, he has been the Director of Research and Public Policy at the US-Mexico Foundation in Washington, D.C. and the Coordinator of International Affairs at the Business Coordinating Council (CCE). He has also served as a consultant to the Inter-American Development Bank.