Nestled in the heart of Mexico City’s historic center lies Barrio Chino, often dubbed the “smallest Chinatown in the world.” This vibrant enclave, spanning just one block long and two blocks wide, offers a unique blend of Chinese and Mexican cultures that belies its compact size.

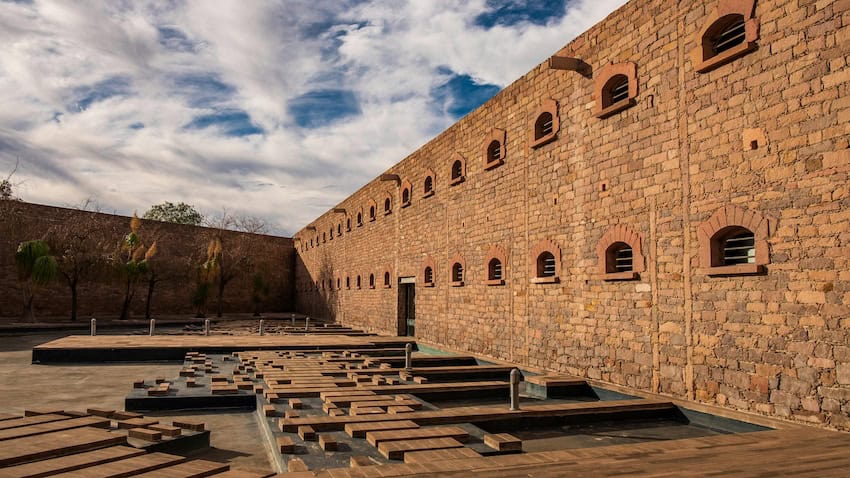

The entrance to Barrio Chino is marked by a striking Paifang, a traditional Chinese archway adorned with tiles imported directly from China. Just a block away stands the Friendship Arch, a gift from the People’s Republic of China in 1992, symbolizing the cultural ties between the two nations.

This small stretch of Calle Dolores is a feast for the senses. Red paper lanterns sway in the breeze, while twinkling lights and colorful stalls create a lively atmosphere. Meander past shops selling everything from green tea to nori wraps to Maneki Neko figurines: the money-making waving cats which, as anyone with a penchant for Asian culture already knows, actually originate from Japan but are wildly popular in China. In between mini-supers are Chinese restaurants flanked by Chinese characters inscribed on the walls.

Young women, eyelashes piled high with mascara and lips tinted a variety of reds and pinks, call out to passerby from behind oversized aluminum pots with steam spilling out from the sides of the lids. To the left is a collection of dough shaped into a bun the size of your fist, each dyed with a neon color so stark one might mistake it for petroleum. For good measure, it’s sold in a classic Chinese to-go container.

There are people everywhere, piling into Chinese-Mexican fusion restaurants rife with the smell of fried food. Visitors can sample dishes like tacos orientales (Oriental tacos) or chop suey a la mexicana, which combine Chinese cooking techniques with Mexican ingredients and spices. On weekends it’s nearly impossible to get from one end of this little barrio to the other without physically pummeling through crowds of families. As one might expect from a Mexico City Chinatown, it’s a noisy place.

However, what stands out the most isn’t its size nor its chaotic ambience. It’s the clear lack of… well, Chinese people. You can feasibly walk every square inch of Chinatown without seeing one person hailing from the PRC. Some of the smaller shops are indeed run by Chinese families, but they’re vastly outweighed in majority.

All of which raises the question — what’s a Chinatown doing here in the Historic Center?

What’s a Chinatown doing in Mexico City’s Historic Center?

Though there have been Chinese people living in Mexico since the colonial period, the history of this distinctive neighborhood dates back to the 1880s, during the presidency of Porfirio Díaz. In an effort to modernize Mexico, Díaz’s government implemented policies to encourage European and Asian immigration. Though not as successful as other Latin American countries in this goal, the policies did attract immigrants, particularly from Lebanon, Italy, Spain and China. Foreign families and workers, many of whom were escaping economic hardships in their homeland, settled in the country.

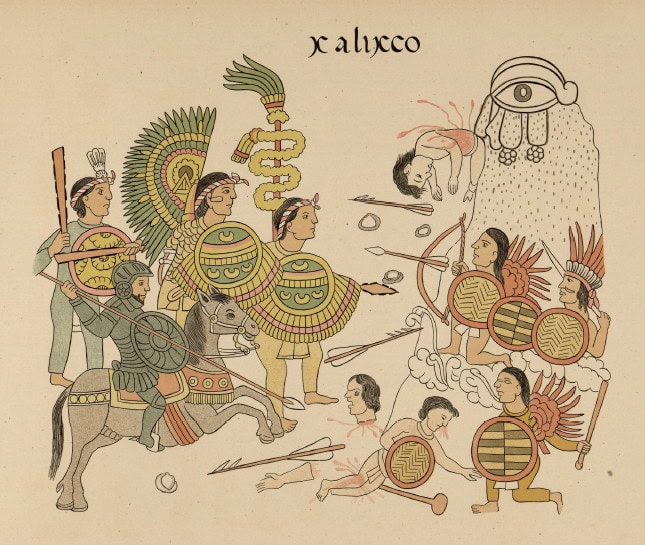

Initially, Chinese immigrants settled in northern Mexico. However, the Mexican Revolution proved to be a tumultuous and dangerous period for these communities. A series of violent and discriminatory acts forced many Chinese residents to flee south to Mexico City. The tragic Torreón Massacre is one of the most egregious, when revolutionary supporters of Francisco Madero ransacked the Coahuila town and murdered hundreds of Chinese men, women and children.

By the 1920s and 1930s, a thriving Chinese community had managed to establish itself around Dolores Street in Mexico City’s historic center. This area became a hub of Chinese immigrant activity, with numerous businesses catering to both the Chinese community and local Mexicans. The streets of Dolores and Luis Moya were lined with Chinese-owned establishments, including restaurants, laundries, bakeries and various shops.

The Chinese immigrants who settled in Mexico City brought with them their entrepreneurial spirit and cultural traditions. They opened “cafés de chinos” (Chinese cafes) that served both Chinese and Mexican cuisine, becoming popular spots throughout the older sections of the city. These businesses not only provided economic opportunities for the Chinese community but also introduced elements of Chinese culture to Mexico City’s urban landscape.

However, this period of prosperity was followed by significant challenges. In the 1930s and 1940s, Chinese immigrants and their descendants faced persecution stemming from anti-foreign sentiment and racist public opinion. This difficult period saw many Chinese-Mexicans struggling to maintain their cultural identity while facing discrimination and political pressure from so-called “anti-Chinese campaigns.”

Despite these hardships, the Chinese community in Mexico City has shown remarkable resilience. In recent decades, there has been a concerted effort to revitalize the Chinatown area. A major renovation project began in 2008, which included the addition of the iconic Chinese arch on Calle Artículo 123. This arch, known as El Arco Chino, was a collaboration between Mexican and Chinese artists and architects, featuring engravings on marble and granite imported from China.

Today, while Barrio Chino may not have a large Chinese population, it remains a symbol of cultural fusion and historical significance. According to El Financiero, Mexico is home to approximately 11,000 Chinese residents, though exact statistics are challenging to obtain. Many Chinese descendants have dispersed to other neighborhoods in Mexico City, such as Viaducto Piedad, Polanco and Cuauhtémoc.

Must-try restaurants in Mexico City’s Chinatown

For those looking to experience the flavors of Barrio Chino, several notable restaurants stand out:

Hong King Restaurant: Founded in 1963, this long-standing Cantonese establishment offers authentic Chinese cuisine, including their renowned Peking duck.

Restaurante 4 Mares: Specializing in Cantonese-style seafood since 1982, this restaurant is known for its salt and garlic fried shrimp.

Tío Pepe Cantina: While not a Chinese restaurant, this historic cantina offers a unique perspective on Barrio Chino, with windows providing direct views of the bustling Dolores Street.

Want to visit but not sure when? Chinese New Year celebrations will take place in Barrio Chino on Wednesday, Jan. 29. It’s a vibrant time of year to visit, as the streets are adorned with even more colorful decorations than usual, and traditional lion and dragon dances are performed. The festivities attract both locals and tourists and is a bright, happy block party you won’t want to miss.

Barrio Chino may be small in size, but it stands as a testament to the resilience and cultural contributions of Chinese immigrants in Mexico. It continues to evolve, offering visitors a unique glimpse into the intertwining of Chinese and Mexican cultures in the heart of Mexico City.

Bethany Platanella is a travel planner and lifestyle writer based in Mexico City. She lives for the dopamine hit that comes directly after booking a plane ticket, exploring local markets, practicing yoga and munching on fresh tortillas. Sign up to receive her Sunday Love Letters to your inbox, peruse her blog or follow her on Instagram.