Over 70% of water resources in Michoacán are contaminated, but authorities are indifferent to the problem, according to a scientific researcher at a university in the state capital.

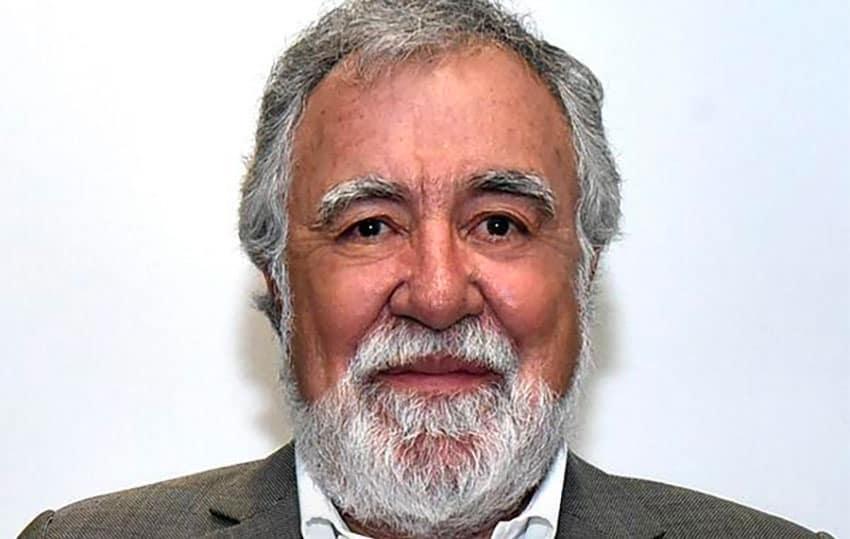

Arturo Chacón Torres, an academic at the Michoacán University of San Nicolás de Hidalgo (UMSNH) in Morelia, said that industry and agriculture are among the polluters of water resources such as lakes and rivers.

“More than 70% of the Michoacán water systems have some degree of contamination,” he told the news website Cambio de Michoacán.

“Basically it’s organic material [that causes the contamination],” Chacón said, apparently using a euphemism for sewage. “[But] there is also industrial contamination and … agrochemicals due to the primary production we have in the state,” he said.

In addition to authorities, many everyday citizens and businesspeople are indifferent to the water contamination problem, said the academic, who researches aquatic ecology and other environmental issues.

Chacón said that Michoacán has 18 natural lakes, 270 reservoirs, 44 rivers, 600 springs and some 6,000 wells. Michoacán is a “strategic state for the production of water,” he said. “The problem is that not even Michoacán society has wanted to understand this.”

Chacón added that the state has a water depletion problem in addition to “growing contamination” of its waterways.

Lake Cuitzeo, Mexico’s second largest freshwater lake, has been allowed to run dry, he said. “It should be the most important lake … for supplying water to central Mexico … [but] we let it dry up,” Chacón said.

“Not having mechanisms to clean up and collect [water to replenish the lake] is institutional irresponsibility,” he said, adding that authorities have not shown any concern for fishermen who depended on Lake Cuitzeo for their livelihood or for health risks associated with the drying up of the lake.

Chacón said that “clandestine” pumps have been detected in the lake, explaining that they have been used to extract water for orchards and households. He also said that “clandestine discharges” into the lake have occurred.

Another UMSNH researcher, Alberto Gómez-Tagle, said last year that waste from pig farms and industrial waste from factories are dumped into the lake.

On the surface of the limited quantity of water in Lake Cuitzeo, there are algal blooms that are “potentially toxic” and could cause disease or even death, Chacón said.

The academic said that the water volume of Lake Pátzcuaro, Michoacán’s most iconic lake, is only 40% of what it was 30 years ago. The lake, he said, is “quite deteriorated,” with contamination from wastewater and agrochemicals. Chacón also said that the amount of silt in the lake is increasing.

The Lerma River, which runs through Michoacán and four other states, is another concern. The river, which has been described as “biologically dead” and “an enormous stinking sewer,” is contaminated with heavy metals that can cause kidney disease and other health problems.

Chacón said that companies with operations near the river, such as Bayer, Chrysler and Nestlé, contaminate the river. Just touching the water along some stretches is “extremely dangerous” because it’s “very contaminated,” he said, noting that some people have died from illnesses related to the pollution.

The Duero River – which like the Lerma flows into Lake Chapala in Jalisco – “is healthy until [Lake] Camécuaro … but after that we have increasing degrees of contamination until its mouth,” Chacón said, explaining that “it’s heavily polluted by agricultural systems.”

The Balsas River is partially contaminated, the researcher added, but cleaner in Michoacán than some other states through which it runs because there are “no significant human settlements or factories” along it.

With reports from Cambio de Michoacán