Mexico will invest US $1.5 billion on border infrastructure between 2022 and 2024, according to a joint statement by President López Obrador and United States President Joe Biden.

According to a joint statement issued after the two leaders met Tuesday in the White House, the two countries are “committed like never before to completing a multi-year joint U.S.-Mexico border infrastructure modernization effort for projects along the 2,000-mile border.”

The joint effort “seeks to align priorities, unite border communities and make the flow of commerce and people more secure and efficient,” the statement said, noting that the U.S. will invest $3.4 billion in 26 projects at its northern and southern borders.

“Mexico has committed to invest $1.5 billion on border infrastructure between 2022 and 2024,” López Obrador and Biden said.

According to an unnamed New York Times source, the money will be used to improve technology that can detect contraband, while the Associated Press said the resources will be used to improve “smart” border technology.

A White House source told NBC News that the Mexican government’s $1.5 billion will go toward a range of new construction projects along its northern border to strengthen the United States’ ability to screen and process migrants. The U.S. official said the exact details of the projects are still being worked out but added the money won’t go to the construction of any kind of border wall or barrier. The aim of the projects will be to improve the speed and security of border screening rather than to deter migrants from crossing into the U.S., the source said.

White House assistant press secretary Abdullah Hasan credited Biden for Mexico’s commitment to invest in border infrastructure.

“[Former U.S. president Donald] Trump in his four years couldn’t finish a border wall, let alone get Mexico to pay for it. President Biden just got Mexico to agree to paying $1.5 billion to improve border processing and security through smart, proven border management solutions,” he tweeted.

In their joint statement, López Obrador and Biden also reaffirmed their commitment to the full implementation of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, saying that the Mexican and U.S. governments would “make our supply chains more resilient and expand production in North America” through “active coordination of our economic policies.”

They committed to “jointly combat inflation by accelerating the facilitation of bilateral trade and reducing trade costs” and announced that Mexico will purchase up to 20,000 tons of milk powder from the United States to assist Mexican families in rural and urban communities as well as up to 1 million tonnes of fertilizer for subsistence farmers.

Among other commitments, Mexico and the United States pledged to work together to address climate change and security issues, including the challenges of fentanyl, arms trafficking, and human smuggling, and to reduce levels of drug abuse and addiction.

The two countries also reaffirmed their commitment “to launch a bilateral working group on labor migration pathways and worker protections.”

“… The tragic deaths of migrants at the hands of human smugglers in San Antonio further strengthens our determination to go after the multi-billion-dollar criminal smuggling industry preying on migrants and increase our efforts to address the root causes of migration,” López Obrador and Biden added.

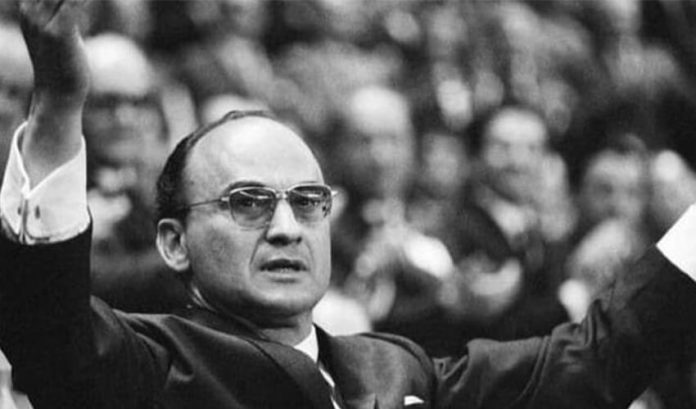

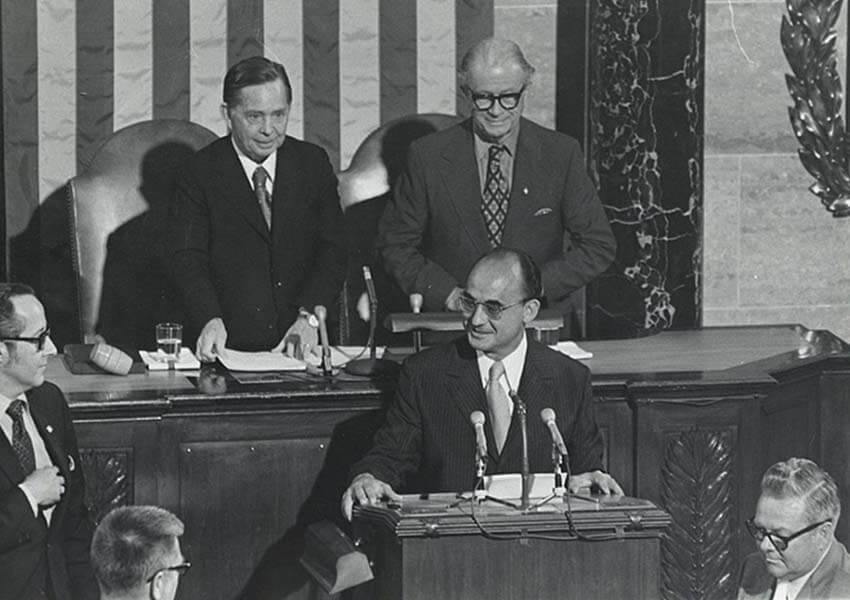

During lengthy remarks in the Oval Office, AMLO spoke about the Bracero Program, under which large numbers of Mexicans worked legally on farms in the U.S. in the middle of the 20th century. “Today, we’re proposing something similar to this program,” he said.

Interior Minister Adán Augusto López Hernández said last month that a formal announcement about a temporary work scheme for 150,000 Mexicans and migrants in Mexico would be made during the president’s visit to Washington, but no such announcement happened.

Martha Bárcena, Mexico’s former ambassador in the United States, said that political conditions in the U.S. made it difficult to get the U.S. government to agree to migration reform. “It’s not that President Biden or the Democrat administration don’t have the political will,” she said.

In an approximately 30-minute response to Biden’s comparatively succinct opening remarks, López Obrador noted that a lot of United States residents have been coming into Mexico to buy gasoline, which is subsidized by the Mexican government.

“We decided that it was necessary … to allow Americans who live close to the border … to get their gasoline on the Mexican side at lower prices,” he said.

“And right now, a lot of the drivers — a lot of the Americans — are going to Mexico … to get their gasoline. However, we could increase our inventories immediately. We are committed to guaranteeing twice as much supply of fuel. That would be considerable support [for U.S. motorists],” López Obrador said. “Right now, a gallon of regular costs $4.78 on average on this side of the border. And in our territory, $3.12.”

López Obrador also advocated working toward the elimination of more tariffs and allowing workers, technicians, and professionals of different disciplines to work in the United States. “I’m talking about Mexicans and Central Americans,” he said, adding that they should be given temporary work visas, which in turn would ensure that the U.S. economy doesn’t stall due to the lack of labor.

“It is indispensable for us to regularize and give certainty to migrants that have for years lived and worked in a very honest manner, and who are also contributing to the development of this great nation,” López Obrador told Biden.

“I know that your adversaries – the conservatives – are going to be screaming all over the place, even to heaven. They’re going to be yelling at heaven. But without a daring, bold program of development and well-being, it will not be possible to solve problems. It will not be possible to get the people’s support.”

AMLO – who didn’t attend last month’s Summit of the Americas because Cuba, Venezuela and Nicaragua weren’t invited – said in late June that he would raise the case of Wikileaks founder Julian Assange in his meeting with Biden, but the Mexican president didn’t mention the 51-year-old Australian during his public remarks. The United Kingdom has approved the extradition of Assange to the United States, where he faces espionage charges, but lawyers are challenging the decision.

In response to López Obrador’s comments – which delved deeply into the history of Mexico-U.S. relations – Biden said he agreed with the “thrust” of what his counterpart said and concurred that “we need to work closely together.”

In his opening remarks, the U.S. president said his government sees Mexico as an “equal partner.”

“… For me and my administration, the U.S.-Mexico relationship is vital to achieving our goals of everything from the fight against COVID-19, to continuing to grow our economies, to strengthening our partnerships and addressing migration as a shared hemispheric challenge,” Biden said.

Although there was no announcement about a new temporary work scheme, the U.S. president highlighted that his administration has already granted visas to a large number of Mexicans and Central Americans.

“My administration is leading the way to creating work opportunities through legal pathways. And last year, my administration set a record. We issued more than 300,000 … [temporary agricultural] visas for Mexican workers,” Biden said.

“We also reached a five-year high in the visas we issued to Central Americans, and we’re on pace to double … [that] this fiscal year,” he added.

With reports from El Universal and Reforma