I strongly disagree with Carlisle Johnson’s recent article in this newspaper in which he suggested that offering migrants a free bus ride home would solve the migrant and refugee problem that Mexico and the United States face.

Like Mr. Johnson, I’ve spent hundreds of hours interviewing and photographing Central Americans in Mexico and the U.S.

I’ve been in — and stayed in — shelters in Tapachula, Tenosique, Ixtepec, Tlaxcala and Mexico City. I’ve interviewed women in Texas detention centers and others who were recently released.

While almost everyone I interviewed would certainly have preferred going home, no one said they would — because the threat of violence was all too real. They were certain that a return home would be a death sentence.

Virtually everyone I interviewed had been victimized by gangs, most often the Mara Salvatrucha and MS-18. Many had had relatives killed.

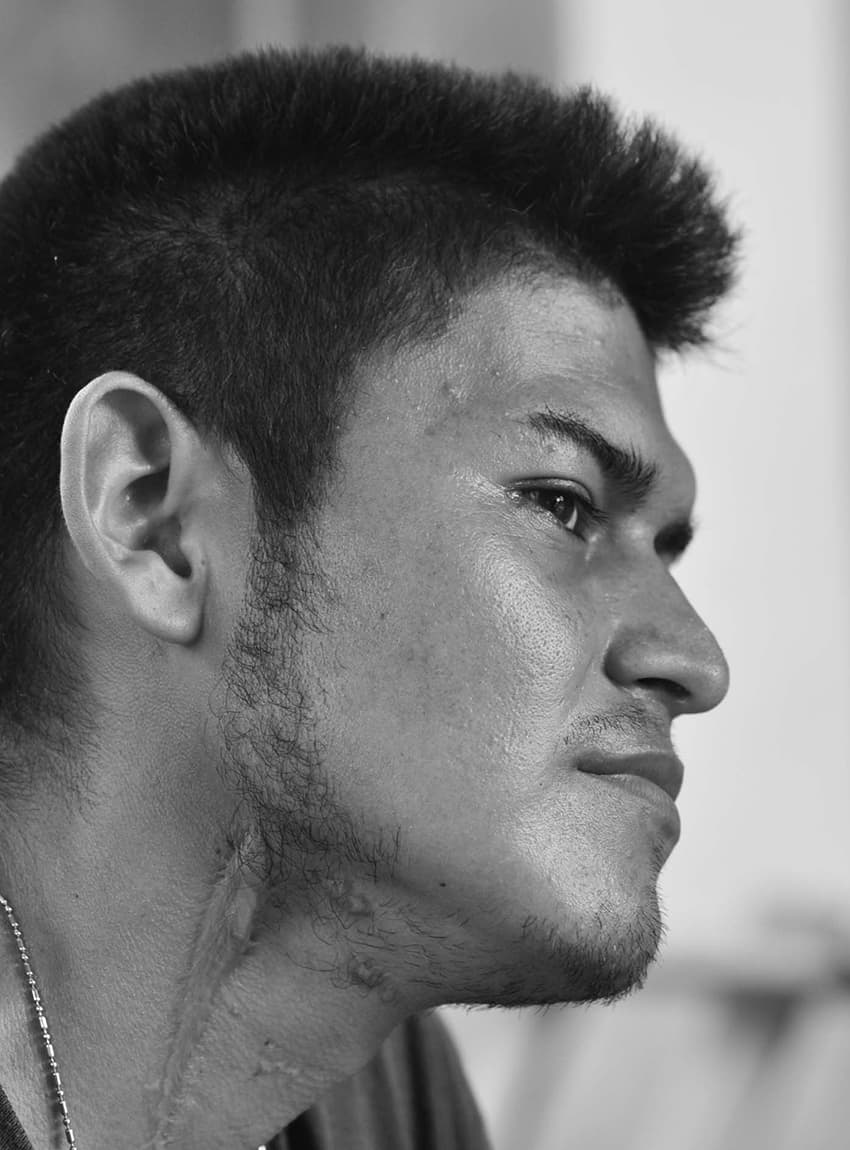

A migrant I met named Felix Antonio said his mother was murdered by a gang (“God knows why,” he told me), and he’d had his throat slashed. A Guatemalan named Herbert said that he and his family fled when gang members told him that if he didn’t join, his family would be killed.

Juan Alberto was living in Tapachula with his family when I met him. A son and a grandson had been killed by Mara Salvatrucha thugs, and he’d fled with his wife, two sons and two grandkids. I asked him if he missed his home in Honduras.

“Oh, so much. So much,” he replied.

I asked him what would happen if he did return to Honduras. He replied in silence, just moving one finger across his throat.

And I disagree with U.S. Vice President Harris’s simplistic message to Central Americans: “Don’t come.”

The vast majority fleeing the Northern Triangle countries of Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala aren’t migrants leaving their countries for economic reasons. They’re refugees fleeing unimaginable violence at the hands of gangs who control much of those countries and the endemic corruption that enables them.

Until the violence is curtailed, they will continue to come.

I once spoke at length with an advocate in Hermanos en el Camino, a shelter in Ixtepec, Oaxaca. I told him that I was amazed how, despite the dangers Central Americans faced on their journey through Mexico, they continued to take the risk.

He told me that their reasoning was this: “If I stay, I die. If I go, I may die. They choose between certain and possible death.”

Joseph Sorrentino, a writer, photographer and author of the book San Gregorio Atlapulco: Cosmvisiones and of Stinky Island Tales: Some Stories from an Italian-American Childhood, is a regular contributor to Mexico News Daily.