The New York Times (NYT) on Thursday published allegations that people close to President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, including his sons, received drug money after he took office in late 2018.

López Obrador — who last month rejected reports that his 2006 presidential campaign received millions of dollars in drug money — denied the allegations before the Times even published them in a report headlined “U.S. Examined Allegations of Cartel Ties to Allies of Mexico’s President.”

At his morning press conference, AMLO, as the president is best known, railed against the newspaper, describing it as a “filthy rag” and calling its journalists “world-renowned professional libelers.”

“…You are deceivers, those from the New York Times and those who sent you to do the report,” López Obrador said.

He also revealed a series of questions sent to his communications coordinator by the NYT’s bureau chief for Mexico, and displayed and read aloud the telephone number she supplied.

The Times responded to AMLO in a post to its public relations account on the X social media platform.

“This is a troubling and unacceptable tactic from a world leader at a time when threats against journalists are on the rise. We have since published the findings from this investigation and stand by our reporting and the journalists who pursue the facts where they lead,” said the statement posted to the @NYTimesPR account.

The allegations and AMLO’s responses

“American law enforcement officials spent years looking into allegations that allies of Mexico’s president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, met with and took millions of dollars from drug cartels after he took office, according to U.S. records and three people familiar with the matter,” the Times report began.

“The inquiry, which has not been previously reported, uncovered information pointing to potential links between powerful cartel operatives and Mexican advisers and officials close to the president while he governed the country.”

The NYT noted that “the United States never opened a formal investigation into Mr. López Obrador, and the officials involved ultimately shelved the inquiry.”

The newspaper also acknowledged that “while the recent efforts by the U.S. officials identified possible ties between the cartels and Mr. López Obrador’s associates, they did not find any direct connections between the president himself and criminal organizations.”

The United States government has jurisdiction to bring charges against foreign officials if it can demonstrate that there is a connection to drug smuggling into the U.S.

Allegation:

The Times said that an informant told U.S. investigators “that after the president was elected, a founder of the notoriously violent Zetas cartel paid [US] $4 million to two of Mr. López Obrador’s allies in the hope of being released from prison.”

AMLO’s response:

López Obrador described the allegation, as set out in the letter sent to Jesús Ramírez by NYT Mexico bureau chief Natalie Kitroeff, as “another calumny.”

He added that Reforma — his least favorite Mexican newspaper — is “much better” than the New York Times.

Allegation:

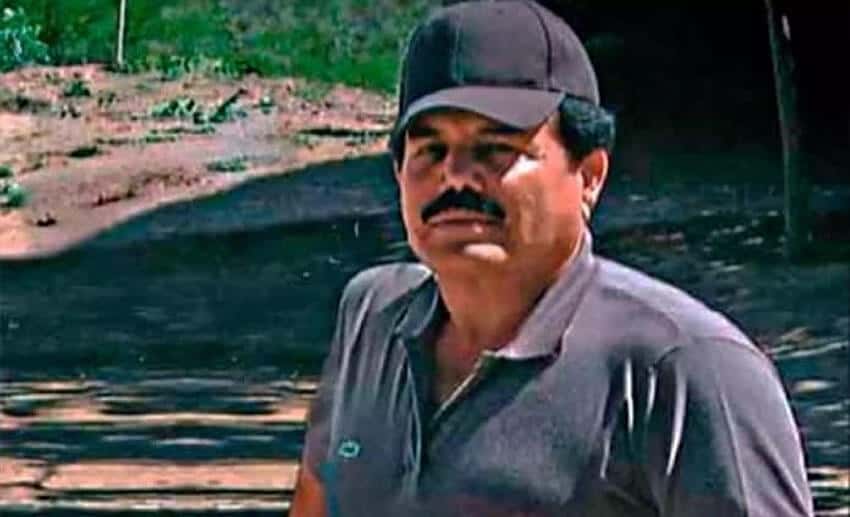

The Times reported that “records show” that U.S. investigators “were told by an informant that one of Mr. López Obrador’s closest confidants met with Ismael Zambada García, a top leader of the Sinaloa drug cartel, before his victory in the 2018 presidential election.”

AMLO’s response:

“Of course it’s false, completely [false],” López Obrador said.

Allegation:

The Times reported that “investigators obtained information from a third source suggesting that drug cartels were in possession of videos of the president’s sons picking up drug money, records show.”

AMLO’s response:

“Where are the videos? It’s an embarrassment. There is no doubt that this kind of journalism is in clear decline. The New York Times is a pasquín inmundo [filthy rag],” the president said.

Allegation:

The NYT said that “U.S. law enforcement officers also independently tracked payments from people they believed to be cartel operatives to intermediaries for Mr. López Obrador, two of the people familiar with the inquiry said.”

“At least one of those payments, they said, was made around the same time that Mr. López Obrador traveled to the state of Sinaloa in 2020 and met the mother of the drug lord Joaquín Guzmán Loera, who is better known as El Chapo and is now serving a life sentence in an American federal prison.”

AMLO’s response:

“In other words, I went to pick up the money. Or we went because while I was meeting the lady [El Chapo’s mother], the person with me received the bribe,” López Obrador said with a wry smile.

“…Look at the distortion,” he added, noting that the letter sent to his communications coordinator asserted that he had traveled to Sinaloa to meet with María Consuelo Loera, who died in December.

“… I went to inspect a road that was built … from Badiraguato, [Sinaloa], to Guadalupe y Calvo, Chihuahua,” López Obrador said.

Allegations won’t affect relationship with US, AMLO says

The president also responded to an inquiry from Kitroeff as to how the Times’ “new revelation” might affect bilateral relations with the United States.

“In no way, [the allegations] can’t have an impact if we’re obliged to maintain good relations with the government of the United States because we’re partners — leading economic trade partners, because we have … a border of 3,180 kilometers, because 40 million Mexicans live and work honorably in the United States and because politics was invented, among other things, to avoid confrontation,” López Obrador.

While he made that remark, AMLO acknowledged that after three media outlets reported on a closed Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) investigation of allegations that his 2006 campaign received drug money, he said, “How are we going to be sitting at the table [with U.S. officials] talking about the fight against drugs if they, or one of their institutions, is leaking information and harming me?”

He said Thursday that “time will tell” whether the new allegations will diminish the trust the Mexican government has in the United States. López Obrador also said he hoped that the United States government would say “something” about the allegations.

“If they don’t want to say anything, if they don’t want to act with transparency, that’s a matter for them. But any democratic government, any defender of freedoms, has to inform,” he said.

John Kirby, spokesman for the U.S. National Security Council, said Thursday afternoon that “there is no investigation into President López Obrador.”

United States Ambassador to Mexico Ken Salazar said earlier this month that the case regarding the alleged illicit campaign funding in 2006 was closed.

Why didn’t the United States pursue the allegations exposed by the NYT?

Citing “three people familiar with the case, who were not authorized to speak publicly,” the Times reported that U.S. law enforcement officials “concluded that the U.S. government had little appetite to pursue allegations against the leader of one of America’s top allies.”

It also said that “for the United States, pursuing criminal charges against top foreign officials is a rare and complicated undertaking,” adding that “building a legal case against Mr. López Obrador would be particularly challenging.”

Again citing the people familiar with the case, the NYT also said that “the decision to let the recent inquiry go dormant … was caused in large part by the breakdown of a separate, highly contentious corruption case.”

It was referring to the case brought against former Mexican defense minister Salvador Cienfuegos, who faced drug trafficking and money laundering charges in the U.S. after his arrest at the Los Angeles airport in 2020.

Under heavy pressure from the Mexican government, the U.S. government, led at the time by former president Donald Trump, dropped the charges against the retired general and granted Mexico its wish to conduct its own investigation. The Federal Attorney General’s Office exonerated Cienfuegos less than two months after he returned to Mexico.

López Obrador, who has relied heavily on the armed forces during his presidency, claimed that the U.S. fabricated evidence against the ex-defense minister, who served as the top military official in the 2012-18 government of Enrique Peña Nieto.

“It’s not possible for an investigation to be carried out with so much irresponsibility, without support, and for us to remain silent,” he said on Jan. 18, 2021.

As a result of the whole affair, the Drug Enforcement Administration “suffered a tremendous blow to its relationship with the Mexican government,” the Times reported.

One example of Mexico’s dissatisfaction with the United States as a result of its investigation against Cienfuegos was the approval of legislation that regulates the activities of foreign agents in Mexico, removes their diplomatic immunity and allows for their expulsion from the country. Another was the the delaying of the issuance of visas that allow DEA agents to work in Mexico.

The security relationship has since improved, and the United States presumably doesn’t want to see it deteriorate again.

An investigation in the United States focusing on allegations that people close to López Obrador received drug money during his presidency would — to say it mildly — not be at all convenient for the U.S. government as it seeks to negotiate with the president and his administration on key issues such as migration and drug trafficking. A recent surge of migrants to the United States is a particular concern for President Joe Biden as he prepares for what appears will be a repeat showdown with Trump at the 2024 U.S. presidential election on Nov. 5.

Another factor in the United States decision to not move forward with its inquiry was likely concern over the reliability of the information its law enforcement officials received.

“Much of the information collected by U.S. officials came from informants whose accounts can be difficult to corroborate and sometimes end up being incorrect,” the Times reported.

“The investigators obtained the information while looking into the activities of drug cartels, and it was not clear how much of what the informants told them was independently confirmed.”

By Mexico News Daily chief staff writer Peter Davies ([email protected])