It’s not often that a city in Mexico gets nationally touted for its cleanliness, fresh air and aerial cable cars that overlook its tangled avenues and mountains looming in the near distance. And even rarer is when a mid-sized city gets designated as a Pueblo Mágico — a denomination typically reserved for Mexico’s quaintest locales.

But in Orizaba — the Pueblo Mágico nestled on the eastern foothills of the Sierra Madre Oriental mountain range in Veracruz — maintaining a pristine appearance has fueled a cultural renaissance in the city’s image and appeal, transforming it from a former industrial center into one of the state’s most celebrated and frequently visited gems.

What to see and do in Orizaba

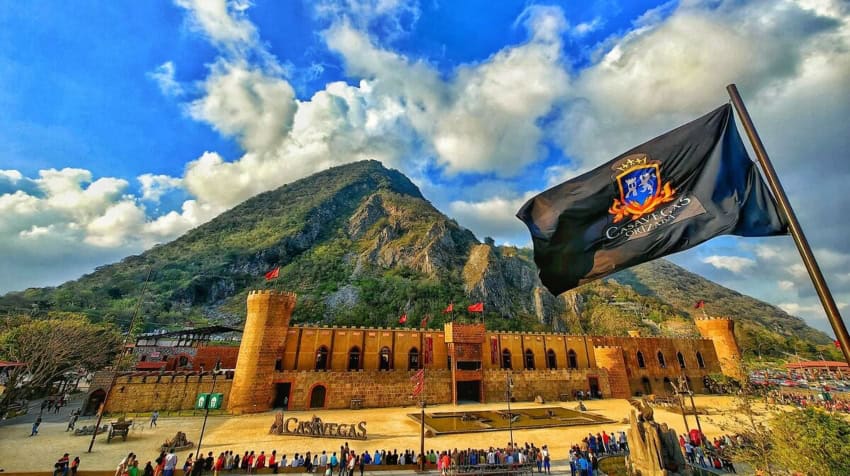

With an impressive array of group activities — which includes unusual attractions like riding a funicular down a hillside, touring a dinosaur-themed park and wandering the château-like grounds of a museum dedicated to Cri-Cri (the stage name of a famous Mexican singer-songwriter of beloved children’s songs) — there’s plenty to keep visitors and locals busy year-round. Add to that a notable cafe and culinary scene known for its provincial dishes and locally-sourced coffee and you’ll begin to understand why Orizaba has become a road trip-worthy destination in recent years. It’s also why I chose to venture there with my family to begin the New Year.

Despite its altitude, Orizaba sits in a lush valley in the shadow of Pico de Orizaba, an active volcano and the tallest mountain in Mexico (ranking as the third-highest summit in all of North America). The region boasts moderate weather year-round, though it is known to get heavy rains from May to October. If possible, avoid going on weekends and holidays, since it gets slammed by Mexican visitors escaping the nearby metros of Veracruz and Puebla.

History and a cleaned-up reputation

Whenever I tell the older Mexican generation about my interest in the city, they give me a funny look, as if to say, “Why would you waste your time visiting there? There’s nothing.” My father — a Xalapa native who used to travel all over Mexico in the 1960s and 1970s before I was born — once told me that I should completely skip going there. When I told him that it’s now a point of interest with a cleaned-up reputation, he wasn’t convinced. So I took him along for the trip with my son and wife; needless to say, he’s now a believer.

Orizaba has pre-Colombian origins, with traces of the Toltecs, Chichimecas and Mexicas. The Indigenous name for the land was Ahuaializapan, or “Pleasant Waters.” In the late 16th century colonial period, it grew into a strategic settlement en route to Puebla and Mexico City before officially becoming a municipality in 1830. During that era, Orizaba and its surrounding areas became a national epicenter of textile factories and tobacco production.

In 1764, the Spanish monarchy monopolized tobacco growth and declared Orizaba and nearby Córdoba as among the few places allowed to grow it in all of New Spain. Wealth and prosperity blossomed for Orizaba during this period, before it fell into a post-Revolution decline, when many of the region’s major sources of wealth were disrupted.

Orizaba’s working-class roots

At its core, Orizaba’s identity became one of working-class industrialism, at one point becoming the temporary headquarters for Casa del Obrero Mundial (House of the World Worker), a socialist organization founded in Mexico City.

Orizaba was also the site of the Rio Blanco Strike in 1907, when workers led a riot against the owners of a textile factory in the nearby town of Rio Blanco. It ended with national military intervention and the death of at least 18 protesters.

An Art Nouveau legacy

Nowadays in Orizaba, you won’t see any overt traces of these social uprisings. Instead, you’ll find the charming architecture of Mexico’s Art Nouveau past. It has all been restored and well-maintained thanks to the vision of current mayor Juan Manuel Diez Francos, who served three non-consecutive terms as mayor and who began Orizaba’s reclamation during his first term in 2007.

Diez’s orizabeño evangelism yielded an invigorated, modernized city filled with quirky offerings: He oversaw the installation of a teleférico — a sky tram that opened to the public in 2013. It is currently Mexico’s highest and third-longest teleférico — according to the enthusiastic guide who greets you upon landing at the summit of El Cerro del Borrego, where vistas await on every side. But be warned: on weekends and holidays, expect waits of up to two hours. The 15-minute ride glides above the town’s bustling core, with various roofs displaying gorgeous murals.

Culinary offerings in Orizaba

The regional foods — especially its coffee — are tremendous draws too. Carlos Iván Spíndola — better known as Perrito Barista, a social media foodie and influencer with 45,500 followers on Instagram whose content centers on Veracruz’s coffee culture — recommends places like Fidelio, a hip, youthful espresso bar and restaurant with a terrace view of the nearby church. Its trendy offerings include poche toast (housemade bread topped with spinach, garlic, arugula and cheese au gratin and then crowned with a perfectly poached egg), strawberry cream matcha and horchata con café.

On Orizaba’s main pedestrian thoroughfare, one can find a bustling strip of businesses, cafes and hotels in the center of town that leads directly to an extravagantly-sized park dedicated to Francisco Cabilondo Soler (the real name of the above-mentioned Cri-Cri) that would rival Mexico City’s finest.

A block away from this plaza awaits Aborigen Cocina de Brasa, a wood-smoked steakhouse that prides itself on regional flair. I suggest the tacos orizabeños — two bean-layered corn tortillas generously piled with grilled chicken and pumpkin. The American-style pork brisket and black pastor, a Yucateco take on tacos al pastor that uses black chile paste, is also impressive. And don’t leave Cocina de Brasa without trying the cochinta pibil: a smoky, spicy heap of tenderized pork mixed with thick adobo and pickled onions served on a fresh banana leaf.

Across the walkway from Aborigen, snag a dessert and post-meal espresso at Hêrmann Thômas Coffee Masters, one of the state’s better-known coffee makers, hailing from nearby Cordóba. Bonus points if you add an affogato carajillo cocktail to the mix, served with a scoop of housemade dulce de leche ice cream.

A magical portal

To be sure, Orizaba has yet to reach international mainstream acclaim at the levels of Mexico’s other most popularly visited Pueblos Mágicos. But it has certainly accrued recognition, particularly among Mexican nationals and expats in the know, which can mean everything there is absolutely packed during the peak season between November and March, especially on weekends.

Orizaba is, as the Mexican government has deemed, a magical portal through which one might better understand Mexico’s beauty. It’s an ideal mix of the country’s glorious past overlaid with the promise of Mexico’s evolving present and future, framed by a sublime backdrop of sierras and flowing waters.

In and of itself, the calm scenery beckons an escape from the chaos of daily life in Mexico’s larger and dirtier cities. In Orizaba, you can unwind, eat plentifully and sightsee (the tigers and alligators prowling the city’s well-kept riverwalk inside a free, open-air zoo had to go unmentioned), all while remaining in a buzzy downtown that is fresh-aired. Perhaps other cities in Mexico can look to Orizaba as a blueprint for revitalization and boosting the local economy. I, for one, would welcome it with open arms.

Alan Chazaro is the author of “This Is Not a Frank Ocean Cover Album,” “Piñata Theory” and “Notes From the Eastern Span of the Bay Bridge” (Ghost City Press, 2021). He is a graduate of June Jordan’s Poetry for the People program at UC Berkeley and a former Lawrence Ferlinghetti Fellow at the University of San Francisco. His writing can be found in GQ, NPR, The Guardian, L.A. Times and more. Originally from the San Francisco Bay Area, he is currently based in Veracruz.