The Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) has once again ordered Mexico to change its laws regarding the use of preventive detention after ruling the Mexican state violated the rights of two men who were imprisoned for more than 17 years before being convicted of homicide charges.

The court said in a statement on Wednesday that mandatory pretrial detention – which applies in Mexico to suspects accused of a range of crimes, including homicide, rape, kidnapping, fuel theft, burglary and firearms offenses – contravenes the American Convention on Human Rights.

The international court ordered the Mexican government to “adjust its internal legal system on mandatory preventive detention” within one year and “review the pertinence of maintaining” the measure.

The Costa Rica-based court made a similar order earlier this year after handing down a ruling in a case involving three men who were arrested on the Mexico City-Veracruz highway in 2006 on organized crime charges. The men were held in pretrial custody for over 2½ years before being released. In January and on Wednesday, the court specifically ordered the elimination of a form of pretrial detention known as arraigo.

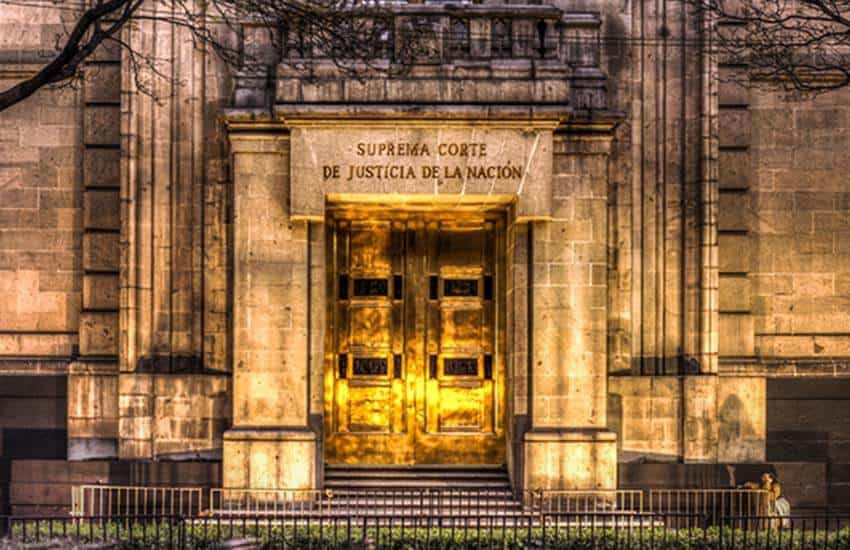

The latest directive comes four months after Mexico’s Supreme Court (SCJN) ruled that prevailing mandatory pretrial detention arrangements were valid except in cases in which alleged perpetrators are accused of tax fraud and smuggling.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs (SRE) acknowledged that the IACHR directed the Mexican state to adjust its laws with regard to pretrial detention to “[comply] with the provisions of the American Convention on Human Rights.”

The convention states that “any person detained shall be brought promptly before a judge or other officer authorized by law to exercise judicial power and shall be entitled to trial within a reasonable time or to be released without prejudice to the continuation of the proceedings.”

It is common for suspects in Mexico to remain in prison for years without facing trial. Arturo Zaldívar, former chief justice of the SCJN, said last year that preventive detention has been abused in Mexico and that pretrial detention should be the exception rather than the rule, used when the accused is a flight risk or there is a danger that evidence will be destroyed or witnesses’ safety will be placed at risk.

The SRE said in a statement that the Mexican state will carefully analyze the IACHR’s ruling with the aim of complying and “ensuring the greatest respect” for the obligations outlined in the American Convention on Human Rights.

The IACHR, which is a branch of the Organization of American States, also ordered the Mexican government to conclude ongoing criminal proceedings against Daniel García Rodríguez and Reyes Alpízar Ortiz in the shortest time possible and continue investigations into the various rights violations they suffered, including torture.

The two men were placed in preventive detention in 2002 after they were arrested on charges of murdering María de los Ángeles Tamés, a councilor in the México state municipality of Atizapán.

They spent over 17 years in preventive detention — a Mexican record — before being released in 2019 when authorities imposed alternate restrictions on their freedom, including a requirement to wear ankle monitors and a prohibition on leaving México state.

García and Alpízar were found guilty last year, though Alpízar’s conviction was overturned on appeal.

The IACHR said that the Mexican state violated several of the men’s rights by imprisoning them for so long before they faced trial, including their rights to personal freedom, the presumption of innocence and equality before the law.

A mandatory preventive detention provision was included in the constitution in 2008, but the number of crimes for which suspects are automatically held in pretrial prison has increased to 16 during the current government.

Abuse of authority, corruption and electoral offenses are among the nonviolent crimes for which mandatory preventive prison applies.

President López Obrador and other federal officials have argued that mandatory pretrial detention is an essential crimefighting tool.

The government said last year that the existence of preventive prison is fundamental for certain crimes “to ensure that the alleged criminals detained for organized crime, serious crimes [such as homicide and rape] … or white-collar crimes don’t avoid … justice during the criminal process.”

With reports from Animal Político, El Economista and AP