Importing yellow corn, wheat and soybeans into Mexico is costing less these days — thanks to a drop in grain prices on the world market, and the peso’s newfound buying power.

However, food prices in Mexico are not going down accordingly.

“In theory, they should lower the prices [of food], but in reality, it does not happen — in Mexico or anywhere,” said Juan Carlos Anaya, director of the Agricultural Markets Consulting Group (GCMA). “This is a complaint heard in other countries.”

In the last 12 months, international grain futures prices have dropped significantly, according to GCMA data: yellow corn costs 29% less; wheat for baking flour is down 24%; durum wheat to produce pastas is down 16%; and soybean paste, which is used by livestock farmers, is down 10%. Mexico uses primarily domestic white corn in food production, but imports yellow corn for use in livestock feed.

Moreover, importers are benefiting from the stronger peso, which has appreciated around 16% this year against the dollar, opening this week at 16.74 per US dollar.

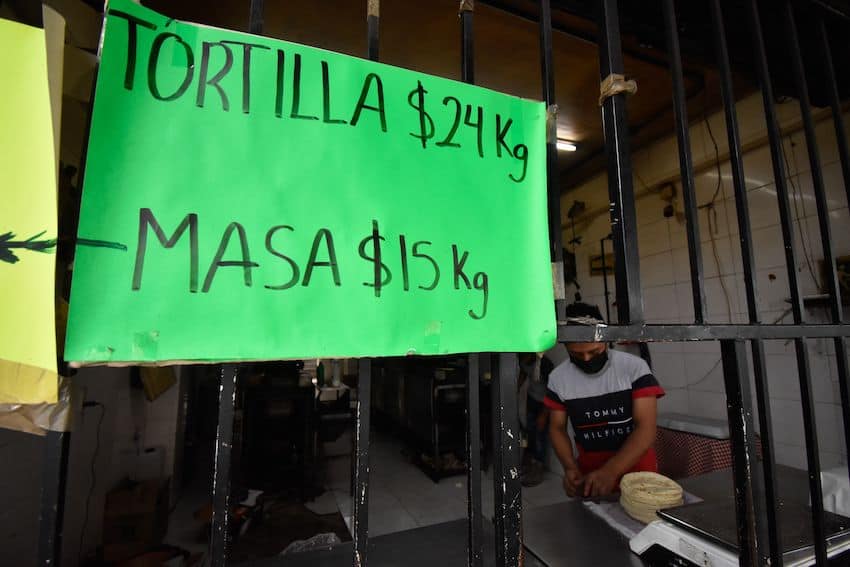

Yet tortilla prices reportedly have gone up 9.7% nationwide this year, cornmeal has risen 13.3% and cereal flakes are up 12.5%. Products made from wheat derivatives are higher, as well, as are prices for pasta.

“They are not going down because it is a captive demand,” Ayala said. “These are staple products.”

Food producers and retailers “argue that when [the cost of these products] rose [with inflation] they had to maintain their prices and reduce their profits” to remain viable, Ayala said. “And now that prices are falling, they are trying to maximize their profits.”

Ayala stopped short of accusing companies of price fixing, but he urged the government’s consumer watchdog agency, Profeco, to look into the drop of grain prices — which has caused Mexican grain farmers to seek increased government subsidies — compared to the prices consumers are paying. “Profeco should review who is getting the most benefit,” he said.

According to the GCMA, Mexico imports 39% of the yellow corn, 95% of the soybeans and 54% of the wheat consumed in the country.

In June, Mexico implemented a 50% tariff on white corn imports to reduce the amount of genetically modified corn used in the country’s food supply. Import levies on white corn had been lifted earlier in the year in response to high inflation and elevated food costs, but the government stated that the exemption had not “generated a significant impact on the decrease in prices in the national market” when it decreed the 50% tariff.

“It is a measure that is not understood, because Mexico is not self-sufficient” in corn production, said Mario Jorge Yáñez, a Mexico-based partner at Hogan Lovells, a law firm with expertise in foreign trade.

Mexico imported only 614,000 tonnes of white corn from January to October last year, but produced 23 million tonnes domestically. However, yellow corn imports from the United States alone are worth about US $5 billion a year. The U.S. announced it would request a dispute settlement panel under the USMCA free trade pact on Aug. 17 in response to Mexico’s stance on GM corn.

Prices for most foods in Mexico are still rising, even as headline inflation declines, with the processed food, beverages and tobacco category up 8.75% annually in the first half of August, and fruits and vegetables up 8.66% according to data from the national statistics agency (INEGI).

With reports from Reforma