It was an hour in on what would end up being a four-hour hike through the Sierra Juárez in Oaxaca when I discovered that my camera’s light meter wasn’t working.

I did the obvious: took the batteries out, wiped them off and put them back into the camera; the meter was still dead.

I did the obvious again. When that didn’t work, I turned the camera off and on several times, turned it upside down, shook it. I may have even given it a gentle tap or two. Nada. I was perplexed. I’d had the camera checked before the trip and swore I’d installed new batteries.

And then I simply swore.

Although I’d previously been to Mexico for a variety of projects, this was my first time heading deep into el campo: rural Mexico. I was going there because I’d written a series of articles about Mexican farmworkers in upstate New York, and after hearing their stories about what their lives were like back in Mexico, decided I needed to see conditions for myself.

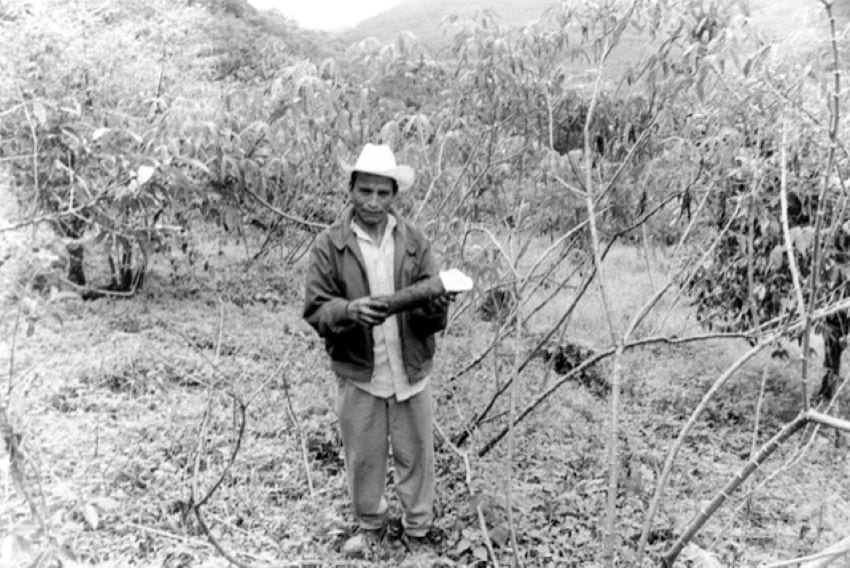

A friend in Mexico City put me in contact with Instituto Maya, an organization that advocates for farmers, and they put me in contact with CEPCO, a fair-trade coffee organization based in Oaxaca that connected me with Candido and some other coffee growers in the Sierra Juárez. Candido’s mission was to make sure I made it to the Oaxaca village of San José Tenango.

To get there meant a seven-hour bus ride through switchback mountain roads at night in a hellacious thunderstorm during which the bus driver used his windshield wipers only intermittently. He did, however, blast Mexican rap music at ear-damaging levels.

After that, it was a three-hour wait in the back of a pickup truck (camioneta) in the predawn chill in Huautla, followed by another trip of just over two hours. Camionetas are essentially rural taxis that drive over mountain paths strewn with rocks and boulders. The soreness in my back, legs and butt — not to mention the bumps on my head from banging it on the overhead rail — attested to just how rocky the ride was.

I spent a few nights in Leonora’s home — she was another CEPCO member — while I waited for someone to take me deeper into the mountains. After three days, I was getting anxious to be on my way and was relieved when Leonora told me to pack my stuff. I was going with Maximiliano to San Martín.

“Take some mandarins,” she told me. “And some toilet paper.”

I was warned that the hike was strenuous, but I bike a lot and didn’t think it’d be a problem; it was.

The steepness of the climb, combined with the altitude and — I’ll admit it — fear, left me exhausted. So I was relieved when Maximiliano signaled after about an hour that we were taking a break. He spoke Mazateco, a native language, and a few words of Spanish. I spoke some Spanish, but he didn’t understand most of what I said. It was a very quiet trek.

I talked with a friend in Oaxaca before going on this trip and mentioned I was concerned about getting sick.

“Joseph,” he sighed, “you know, Mexicans get sick too.”

So I decided not to worry. But during that short break, I watched Maximiliano as he crouched behind a large rock, filled a small Coke bottle with water and took a few sips. I assumed there must be a stream. When I went to look, I found that the water came from a muddy puddle.

I decided it was time to start worrying.

Soon afterward, I took my camera out of my backpack to take a few shots, and that’s when I learned something was wrong with my light meter. When Maximiliano signaled it was time to continue, I stashed the camera in my backpack and walked on, about as depressed as I ever was.

Leonora said the hike would be three hours, and when we reached that point, I asked Maximiliano (as well as I could) how much longer it would be. He must have understood me because indicated “a little more.”

We continued on, me believing that the end of the journey was always just around the next bend. I was having some trouble keeping up with him. I kept pace going uphill, but he dusted me on the downhills and flat stretches. Imagine my chagrin when I learned he was 72. I was a youthful 48.

Mercifully, after another hour, we arrived in San Martín. It was barely a village. Homes were widely spaced along a dirt path and were constructed of wood and tin. It was the poorest village I’d ever been in.

Maximiliano took me to Abelardo and Hortencia’s home, and they graciously agreed to let me stay. When Abelardo saw I was shivering, he kindly gave me a soda while Hortencia heated some soup.

It’s difficult to photograph without a light meter, but I made adjustments by over- and underexposing each shot. I was doing this for the first day when, late in the afternoon, the meter bounced back to life. I had no idea why but was extremely grateful. I then went nuts.

I spent two weeks photographing in San Martín and in Santa Catarina, shooting 40 rolls of film, a total of just over 1,400 images. I photographed women cooking, people harvesting coffee, doing other work. Then, as I was leaving Santa Catarina, the meter died again but my work was done.

When I got back to San José Tenango, I told Leonora what happened. Without any hesitation, she said, “It was Chigonido.”

I didn’t understand. “Who’s Chigonido?” I asked, reproducing the name as best I could.

“Chigonido is the local god,” she explained. “He didn’t want you to take photographs.”

“But people were OK with me taking photographs,” I said.

“It does not matter,” she said. “If he does not want you to take photographs, you cannot take photographs.”

I told several people in the village what had happened. They all confirmed that it was because of Chigonido — even a college-educated teacher agreed.

When I took the camera to a store in Oaxaca, I expected to learn there was a serious problem and had already decided to call a friend back in the United States and have him ship down my other camera. But there was no need. The problem was the batteries: they were dead.

Later, as I thought about what happened, I couldn’t understand how dead batteries could come back to life for two weeks, allowing me to shoot 40 rolls of film before dying again, this time permanently. The only explanation I’ve come up with — and I’ll admit it’s a remote possibility — is that maybe the people back in San José Tenango were correct.

Or, rather, partially correct. Maybe Chigonido did step in. But instead of preventing me from photographing, he brought the batteries back to life, bailing me out.

Joseph Sorrentino is a regular contributor to Mexico News Daily.