The Huei Atlixcáyotl festival, Puebla’s huge event of traditional dance that takes place every September in Atlixco, has roots in the pre-Hispanic Nahuatl peoples of the area, but it wouldn’t exist today if not for a New Yorker.

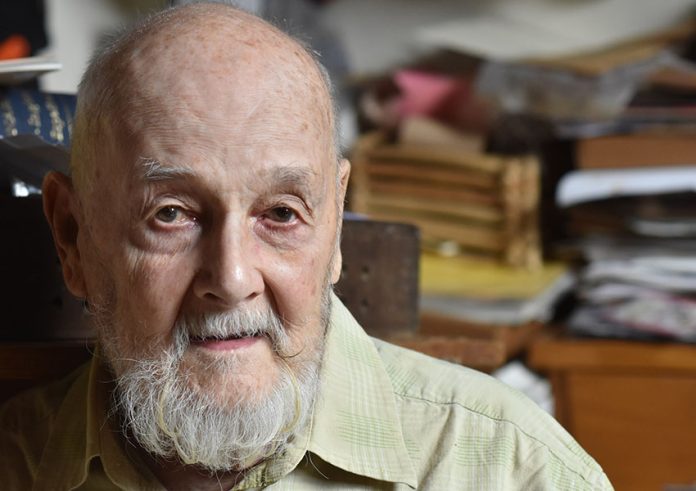

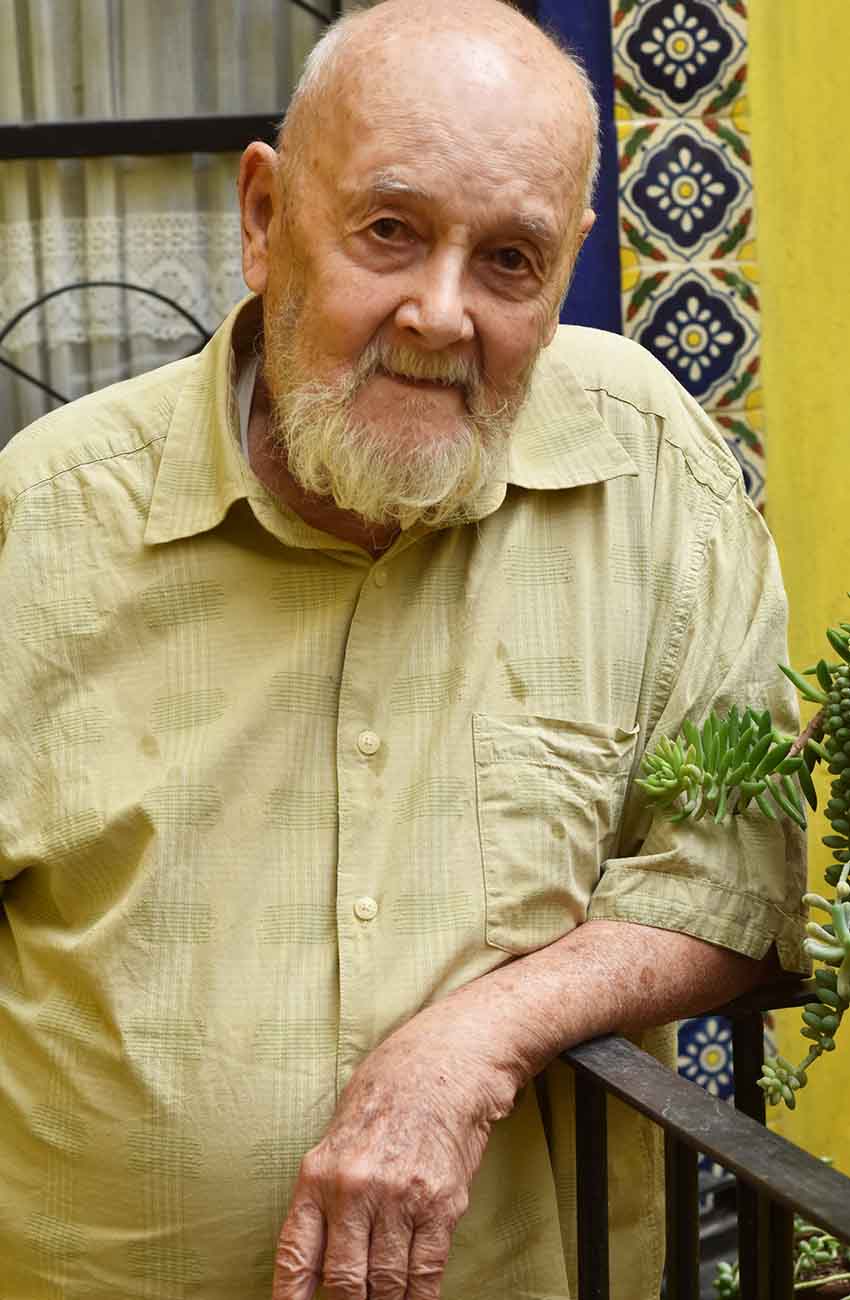

To say Cayuqui Estage Noel has had an interesting and peripatetic life would be a gross understatement. Born Raymond Harvey Estage Noel in Buffalo, he has lived in Mexico since 1954, and except for a couple of trips to New York to earn money and a few others to Guatemala, he’s never left, bouncing between Atlixco and Oaxaca, Campeche and other parts of Puebla.

He’s studied dance, music, acting and anthropology — the latter subject with Margaret Mead — taught any number of topics, directed plays, researched regional dances. Recently, he was named a “Tesoro Humano Vivo” (Living Human Treasure) by the municipal government in Atlixco for his role in bringing the festival into existence in 1965.

After seeing the traditional Guelaguetza festival in Oaxaca, he was inspired to create a venue for Puebla’s traditional dance. He worked with representatives of Atlixco to arrange the city’s first Atlixcáyotl by visiting surrounding villages and convincing locals to perform in the event he was helping arrange.

The festival, which the state government named in 1996 as part of Puebla’s cultural patrimony, is a popular Atlixco event that was just celebrated again this past Sunday for another year. While the state government spells the event as the Huey Atlixacáyotl, and still others the Hue Hue, as a founder of the event, Estage insists that it should be spelled Huei Atlixcáyotl.

Estage, who’s studied dance, music, acting and anthropology — the latter subject with Margaret Mead — taught any number of topics, directed plays, and researched regional dances, was recently named a tesoro humano vivo (living human treasure) by Atlixco’s municipal government.

But he’s probably best known in Mexico for organizing the festival.

Ironically, Estage originally had no intention of staying in Atlixco the first time he saw it.

“I was there for 20 minutes,” he said. “I had no interest in coming to Mexico. Guatemala was my goal. The information about Mexico was that it was [filled with] vaqueros (cowboys) and that wasn’t very interesting. But Guatemala, with Indians in their costumes, cities lost in the jungles — that interested me. I wanted to go to the jungle.”

In fact, Guatemala was where he got the name Cayuqui: he was trying to sell a boat to some locals, and his Spanish was pretty much nonexistent at the time, so they thought he’d said, “Yo soy Cayuqui,” (I’m Cayuqui). Later, when he became a Mexican citizen, he dropped his first two given names and replaced them with Cayuqui.

During his time in Guatemala, on a trip to Guatemala city, he met a young man from Atlixco who invited him to visit. That second trip changed his mind, and he made Atlixco his home.

“I rented a house up on the hill,” he said. “Ten pesos a month. No running water, no electricity, no bathroom, but I didn’t care. I was enthralled with living in Mexico. I bought an oil lamp; I thought it was very romantic, exciting. I bought my water from an old man who brought two oil cans of water, 50 centavos each one, on the back of his donkey. I had the corn field for my bathroom.”

On a trip back to New York to earn money, Estage’s house in Atlixco was ransacked, and so he moved to another house, a decision that would be fateful.

“I rented a room. An old woman who had been in the [Mexican] Revolution — she cooked for [Álvaro] Obregón, knew [revolutionary] Pancho Villa — she told me about the customs of old Atlixco, the dress, which I used later for the Atlixcáyotl.”

Then he visited Oaxaca, another fateful decision.

“I saw the Guelaguetza. I said, ‘Wow. this is incredible that these people exist. We have nothing this fabulous in Puebla.’”

In the Guelaguetza, dancers from all over the state of Oaxaca converge on the city of Oaxaca in July. When he started visiting villages around the state, he saw something very different. “The dances in the villages were much more interesting than what was in the Guelaguetza. I became dissatisfied with the Guelaguetza, but it inspired me to start the Atlixcáyotl.”

He returned to Atlixco and started talking with people in the nearby villages.

“No one in Atlixco was interested in going [there],” he said. “You have to sleep on straw mats, get bitten by fleas. No one would go to the villages. To this day, there are people who have gone to Disneyland, they go to east L.A., New York, but they don’t know the villages around here.”

But Estage felt right at home. And on December 20, 1965, he brought the dancers he’d met in the villages to Atlixco for the first iteration of the festival.

Depending on the source, Atlixcáyotl is Nahuatl for either “the Great Fiesta of Atlixco,” or “the Tradition of Atlixco.” “We have about 17 or 18 groups that perform,” Estage said, “and each group has at least 20 people — between 20 and 40.”

The dances aren’t truly pre-Hispanic, he is careful to point out. “There’s nothing pre-Hispanic today except in the museums. Many [dances] have pre-Hispanic roots, but they are influenced by European music and dance.”

These days, he lives part of the time in Campeche, in a Mayan village, in a little house made of sticks and mud and with a dirt floor and a palm roof — a place in which he’s perfectly content. He was a little vague on his role in the Atlixco festival this year, saying, “I sneak in when they let me.”

But he is adamant about what the Atlixcáyotl should be. “Atlixcáyotl must remain a family fiesta, never an event.” In Oaxaca, he said, “They built a roof over the Guelaguetza. That ruined it.”

And after all these years, he revels in the informality the event still has. “If a dog goes on stage, they shoo it off,” he said. “Dogs are part of our culture. To see a dog on stage to me is something very good.”

He’s lived in Mexico now for almost 70 years, and he didn’t hesitate when asked what it was that attracted him to — and keeps him in — Mexico. “The people,” he said. “They’re marvelous. So warm and friendly and interesting. And so funny. Great sense of humor. I think they’re the happiest people in the world. The best decision of my life was to leave the United States and live here.”

Estage says he has everything he needs in Mexico.

“We don’t have money, but you don’t need money. We have enough to get along on. And it’s changing. We’re [Mexico] becoming gringos. People are becoming interested in money, unfortunately. But when I came here, the rhythm of life was so easygoing. It was like a waltz. People worked as long as they wanted to. They liked what they were doing. They didn’t get paid very much money but you didn’t need very much money. I’m a Jack of all trades, master of none. I have enough to get by.”

It seems like the man who renamed himself Cayuqui was born in the wrong era, that he’d be just as happy — or happier — in a small pre-Hispanic village, learning traditions and dances from the village elders and swapping stories with them.

Joseph Sorrentino, a writer, photographer and author of the book San Gregorio Atlapulco: Cosmvisiones and of Stinky Island Tales: Some Stories from an Italian-American Childhood, is a regular contributor to Mexico News Daily. He currently lives in Chipilo, Puebla. More examples of his photographs and links to other articles may be found at www.sorrentinophotography.com