A total of 66 people were kidnapped in Culiacán, Sinaloa, on Friday and 58 of that number have returned to their homes, state authorities said Sunday.

Men, women and children were reportedly abducted on Friday by armed men who forced their way into their victims’ homes in various parts of Culiacán, a municipality that includes the state capital of the same name as well as rural and coastal areas.

State authorities initially said that 15 people were kidnapped, but that number was later revised to 66.

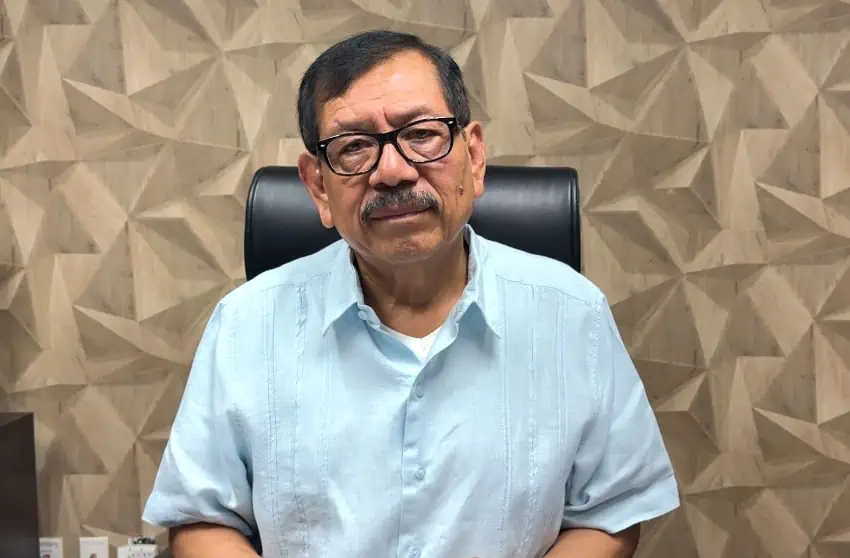

Public Security Minister Gerardo Mérida Sánchez said Sunday that a total of 58 people had returned to their homes, leaving just eight abductees — all adults — unaccounted for. He said that state authorities were working with their municipal and federal counterparts to locate the eight missing people.

The security minister didn’t say whether authorities had located and rescued the 58 people or whether they had returned to their homes on their own account after being released by their captors.

However, the El Financiero newspaper reported that the abductees were freed by their captors in various parts of Culiacán, and that “some were assisted to return to their homes, while others preferred to return on their own.”

Mérida said that none of the 58 people who have returned to their homes wanted to file an official complaint with authorities. He expressed confidence that “someone” would do so in due course and thus assist authorities to establish what happened on Friday.

There are limited details about the abductions, and it is unclear who perpetrated them and for what reason. Mérida on Friday attributed the abductions to “criminal groups,” but didn’t identify any by name.

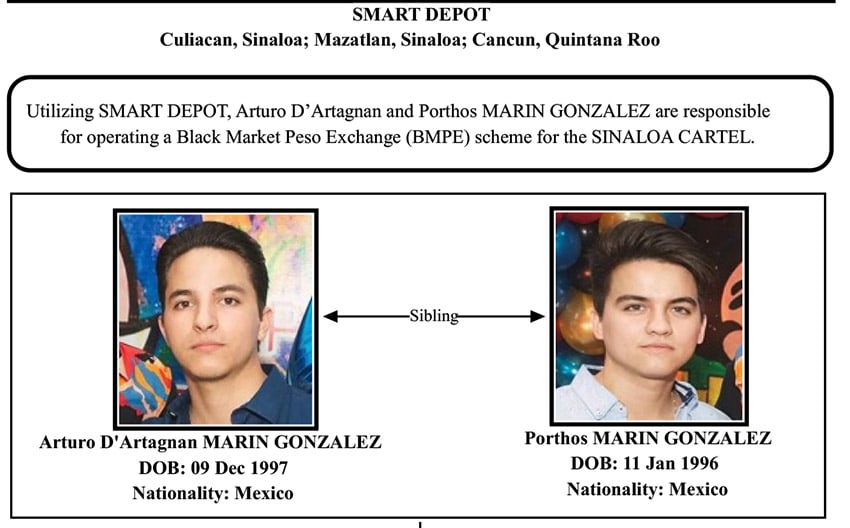

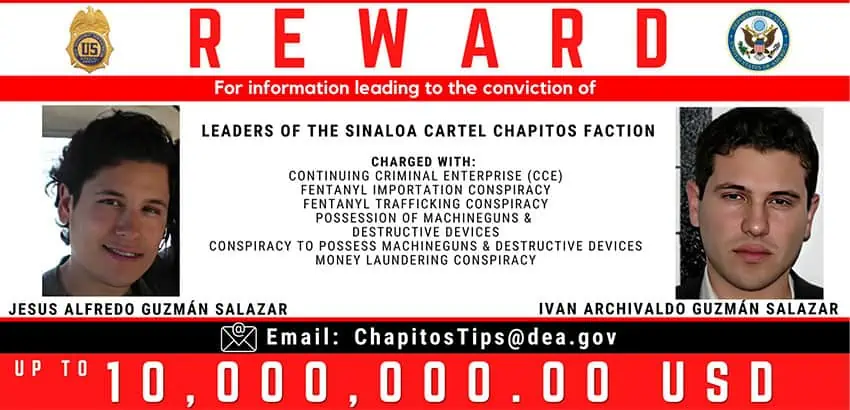

Sinaloa is the home state and foremost stronghold of the Sinaloa Cartel, the powerful criminal organization formerly led by imprisoned drug lord Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán.

Two factions of the same cartel, one led by Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada García and another led by sons of Guzmán (Los Chapitos), have been engaged in a turf war in the state.

President Andrés Manuel López Obrador suggested Monday that the abductions on Friday were related to the dispute between the competing factions.

Mérida on Sunday referred to the 66 people who went missing as “absentees” rather than abductees, and said that authorities had no “certainty” that kidnappings had in fact occurred.

For his part, Sinaloa Governor Rubén Rocha Moya thanked federal authorities including the army and the National Guard for their “constant support” in the wake of the disappearances on Friday. Some 1,800 soldiers and National Guard members have participated in the search for the missing persons, according to López Obrador.

In a post to the X social media platform, Rocha said that a search operation would continue until the eight remaining missing persons have been found. On Friday, the Morena party governor described the kidnappings as “things that unfortunately happen,” a remark seized on by Xóchitl Gálvez, presidential candidate for a three-party opposition alliance.

“I don’t think these are things that happen,” Gálvez said Saturday, asserting that the governor’s remark was an attempt to “normalize violence” and have people see the abduction of “seven families [including] wives and children” as “normal.”

Violence and insecurity will be a major issue in the contest to become Mexico’s next president. All three presidential candidates — Claudia Sheinbaum of the ruling Morena party, Jorgé Álvarez Máynez of the Citizens Movement party, and Gálvez of the Strength and Heart for Mexico coalition — endorsed a “Commitment for Peace” document drawn up by Mexico’s Roman Catholic leadership earlier this month.

The presidential election will take place June 2.

With reports from La Jornada, El Financiero and El País