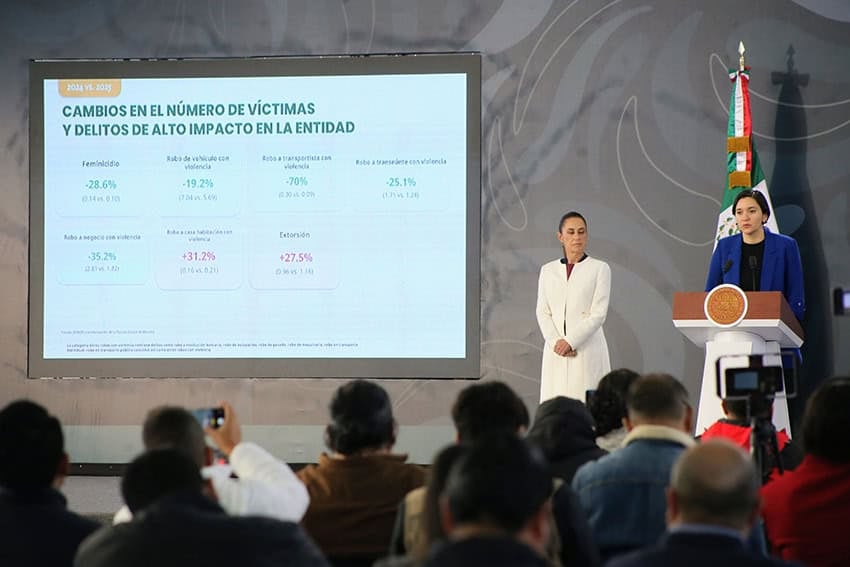

President Claudia Sheinbaum held her Thursday morning press conference in Cuernavaca, capital of the state of Morelos.

At the beginning of her mañanera, Sheinbaum commented that it wasn’t as warm as she expected it to be in the “City of Eternal Spring,” which sits at a lower altitude than nearby Mexico City.

After presentations from security officials, including a review of the 2025 homicide numbers, the president opened the floor to reporters.

What is the government’s main security goal?

After the presentation of data that showed that homicides declined 30% in 2025, a reporter asked the president what the government’s “main” security goal was for its six-year term.

Sheinbaum responded that it was “difficult” to set a numerical goal for the reduction in crime and violence her government is seeking, but stressed that its “commitment” is to reduce the incidence of homicides and other offenses every year it is in office.

“Every month and every year we’re going to continue to reduce [crime], not just homicides, but also a lot of offenses that are known as property crimes, which affect citizens a lot,” she said.

Mexico’s extortion crisis

Cartels charge “piso” or protection on a big range of businesses, driving discontentment for the generally popular President Sheinbaum. People cannot simply accept a cartel tithe as cost of doing business. I write in the NYT.↓ https://t.co/WzwhG2BlXH

— Ioan Grillo (@ioangrillo) December 5, 2025

“Vehicle theft. Violent crimes in particular; violent burglaries of homes,” Sheinbaum said.

She stressed that federal authorities would work with their state counterparts to reduce crime, including extortion.

During a meeting last month with state governors, the Mexico City mayor and federal security officials, Sheinbaum pleaded for a concerted effort to combat extortion, the one “high-impact crime” that has not been curtailed since she took office in October 2024.

The fight against the crime is now supported by a national anti-extortion strategy and a new anti-extortion law.

Government seeking swift investigation into deadly rail accident

Sheinbaum told reporters that her government has asked the Federal Attorney General’s Office (FGR) for “swiftness” in its investigation into the Dec. 28 Interoceanic Train derailment that claimed 14 lives and injured scores of other passengers.

The accident occurred in the state of Oaxaca on the railroad that links Salina Cruz, Oaxaca, to Coatzacoalcos, Veracruz, across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. The cause of the derailment has not yet been been definitively established.

New details emerge as investigation of deadly train accident inches forward

Sheinbaum said that her government has asked the FGR to present the results of its investigation as soon as possible.

“Obviously,” she added, the FGR needs to conduct a “thorough investigation” into the tragedy.

Eleven days after the accident, the railroad between Salina Cruz and Coatzacoalcos remains out of action. Passenger and freight trains normally run on the line, which was modernized during Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s presidency and has been touted as an alternative to the Panama Canal.

The Mexican Navy is responsible for the operation of the railroad, a fact Sheinbaum acknowledged on Thursday morning.

“It’s part of the government of Mexico,” she said, adding that an insurance company and the government have the responsibility to provide “comprehensive” compensation to the victims of the accident and their family members.

Did a Morena lawmaker forget she was carrying 800,000 pesos in cash when crossing into the US?

A reporter asked the president about Alejandra Ang, a Morena party deputy in Baja California who on Monday was reportedly detained for five hours by U.S. authorities at the border crossing between Mexicali and Calexico, California, for failing to declare that she had 800,000 pesos (US $44,500) in cash in her vehicle.

U.S. authorities seized the cash as it exceeded the US $10,000 amount that can be taken into the United States without being declared.

In a statement, Ang said that the money belonged to her and her husband and that it was the product of years of saving and the sale of a vehicle. She said that the money would be used to purchase another vehicle and that “by mistake” she didn’t “safeguard” it at her home before heading to the border.

“I am attending to the administrative process to explain, document and recover the money,” Ang said.

“… I also want to specify that my [travel] documents weren’t taken away or revoked,” she said, apparently seeking to differentiate her situation from that of Baja California Governor Marina del Pilar Ávila, whose U.S. visa was revoked last year.

Sheinbaum indicated that she was in favor of an investigation into the incident involving Ang.

“In this case, I don’t have more information, but we’re going to see if it’s an issue of [interest to] the state Attorney General’s Office or the Federal Attorney General’s Office,” she said.

Asked whether she had a general message for elected officials, the president said they should behave appropriately.

“I’ve said it many times and I maintain [the same view]. It’s a message for everyone, not just … [the officials] who belong to our movement: Power is humility, and one must always behave in a way that serves the people, maintaining an honest life,” Sheinbaum said.

By Mexico News Daily chief staff writer Peter Davies (peter.davies@mexiconewsdaily.com)