Last week, I wrote about the ideological guardrails shaping U.S. trade and economic policy. To recap: the need to decouple from China, the re-industrialization of the U.S. economy, the shift from free trade to managed (or “fair”) trade, and the idea that economic policy isnational security policy.

Now, I know you’re all eager to get to the answer promised in the title — but we’re not there yet. Before that, we need to understand the magnitude of the opportunity, and we can’t do that without talking about the main driver behind these policies: China.

Over the past 20-plus years, three major shifts reshaped the global economic and trade system.

First, manufacturing capacity. Two decades ago, the U.S. share of global manufacturing output was nearly triple China’s. Today, China’s manufacturing output is roughly double that of the United States.

Second, export market share. Before joining the World Trade Organization, China accounted for a modest 3% of global exports, while North America held around 20%. Today, China stands at roughly 12%, and North America at about 14%.

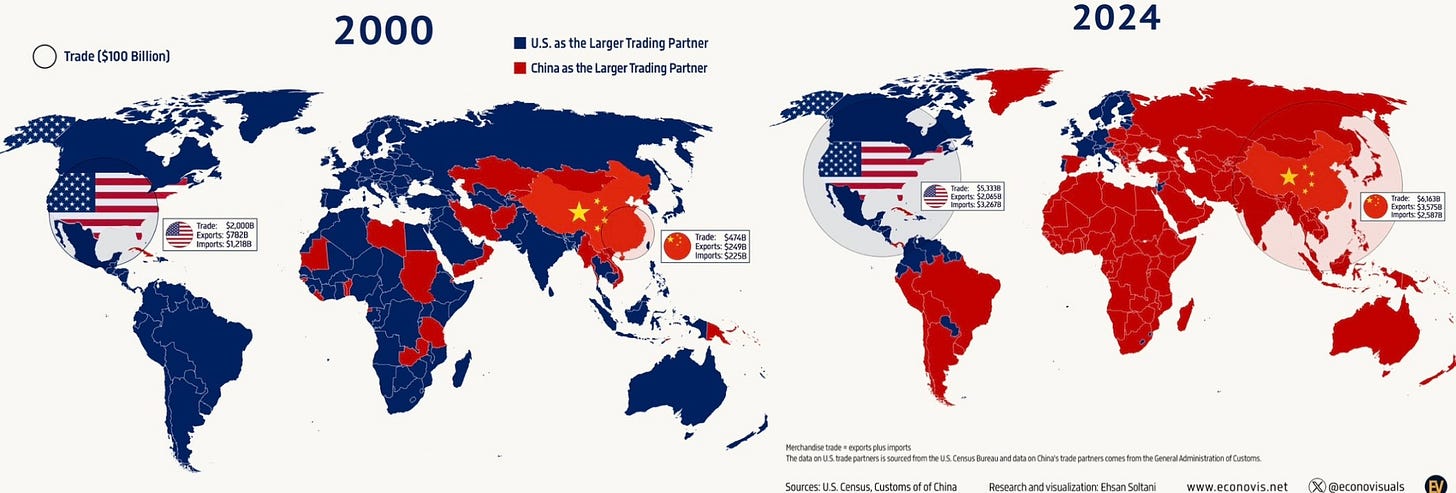

Third, global trade dominance. Twenty years ago, around 80% of countries traded more with the U.S. than with China. Today, nearly 70% trade more with China.

The most common — and mistaken — conclusion drawn from this data is that China simply became the “factory of the world.” But when you look at the destination of Chinese exports, the picture changes. The United States is China’s largest trading partner by far — more than three times larger than its next partner, Japan (excluding Hong Kong).

That alone should be a wake-up call. The real question isn’t whether the U.S. can outcompete China on its own — it’s how North America competes together.

So yes, these are a lot of numbers. But what do they actually mean?

In short, over just two decades, China achieved the largest and fastest expansion in production, economic growth and global market share gain of any country in human history. When China entered the WTO, North American integration and production were on a strong upward trajectory — some might even have predicted exponential growth. Then China entered the picture, and North America plateaued. The U.S. outsourced jobs, technology and innovation to China and other Asian economies. The North American engine — the United States — turned its focus elsewhere. Things didn’t go that badly for North America, but we’ve never seriously explored the counterfactual: how different things could have been.

Let’s go back to the numbers to put the opportunity in perspective. Over the past seven years, China’s share of U.S. imports has declined by 8 percentage points. The biggest winner so far? Mexico — which captured two of those eight points in just the last three years.

That shift fueled a years-long conversation among businesspeople and analysts that usually started with some speaker saying something like: “Nearshoring, friendshoring, ally-shoring — pick your favorite, but this is a historic opportunity.”

And all that excitement was about those two points. It truly changed everyone’s expectations of Mexico.

What makes this even more striking is that during those same years, Mexico hasn’t had a strong pro-investment economic policy — in fact, arguably the opposite. Economic growth has been weak; and I’m being generous with that statement. And yet, foreign direct investment keeps hitting record highs, industrial parks are running at full capacity, and exports to the U.S. keep rising. Mexico is now the United States’ top trading partner, both in exports and imports.

Let me leave you with one final data point to underline the scale of what’s at stake. China has roughly 2 billion square meters of industrial parks. Mexico has about 100 million. If Mexico were to capture just 5% of China’s industrial real estate footprint, it would double its total industrial capacity overnight (yes, I know the geographic differences — just bear with me).

I promised short essays, and this one has already pushed the limit. It’s impossible to compress all of this into a few paragraphs, but the message is clear. North America once had the chance to become the world’s leading technological, manufacturing and innovation powerhouse. That opportunity slipped through our fingers around the year 2000.

The good news? It’s not gone forever. But getting it back requires coordination, trust and serious work across multiple fronts. I’ll share my thoughts on how — and where — in the next pieces.

Stay tuned.

Pedro Casas Alatriste is the Executive Vice President and CEO of the American Chamber of Commerce of Mexico (AmCham). Previously, he has been the Director of Research and Public Policy at the US-Mexico Foundation in Washington, D.C. and the Coordinator of International Affairs at the Business Coordinating Council (CCE). He has also served as a consultant to the Inter-American Development Bank.