I first came upon the tiniest state in Mexico by accident two decades ago. I was hurtling down the Huamantla-Puebla highway when an incongruous castle with orange turrets appeared to our left.

My guide told me that it was some kind of hotel, giving me the perfect pretext to ask to stop and investigate. It was only at that point that I realized we were in what felt like a “no man’s land” that was called Tlaxcala.

The Hacienda Soltepec hotel was an odd mixture of cheerful and imposing, with a small chapel to the right, a pretty courtyard and an elegant wooden reception desk where I was surprised to find out that, in addition to a buzzing restaurant that was a magnet for fine families from around Mexico, there were squash and tennis courts, a gym and a sizeable heated indoor swimming pool.

There began a series of visits to the state of Tlaxcala — hosted and inspired by Javier Zamora, from an old Tlaxcalan family who bought the 17th-century hacienda in the late 1940s.

These trips included the capital city of Tlaxcala, where, in addition to the colonial churches, monastery and arches, I was enchanted by the old Xicohténcatl Theatre and a visit to a traditional maderería, where I had a mini wooden baseball bat carved and painted for my youngest child; the walking sticks of San Esteban Tizatlán are one of the state’s signature folkcrafts.

I also had a long and colorful night in August where I took my kids to soak in the annual party held for the Virgen de la Caridad in Huamantla — fireworks and funfair included —aptly known as Noche que Nadie Duerme (The Night When No One Sleeps).

One of my top Mexican memories of the last 30 years belongs to Tlaxcala: a 4 a.m. hot-air balloon ride of soaring beauty with my daughters and mother, with its unforgettable view of the Popocatépetl and Iztaccíhuatl volcanoes at sunrise, the rolling green contours of the land below and birds fluttering under our basket as we silently drifted.

I kept going back — for a visit with an archaeologist to the vibrant murals of Cacaxtla and to the ancient site of Xochitecatl, the latter with a unique spiral pyramid and said to have had a matriarchal society.

I also went on a pulque-permeated Huamantlada, where I watched lunatic youths run in front of incensed bulls in the quaint streets of a colonial city of Otomí origin.

There was a jaunt up the Malinche, a.k.a. Malintzin, volcano — known before the conquest as Matlalcueitl, meaning “Lady of the Green Skirts”) — Tlaxcala’s highest peak at about 4,440 meters. Now one of the region’s main ecotourism destinations, it’s soon to become a magnet for mountain bikers.

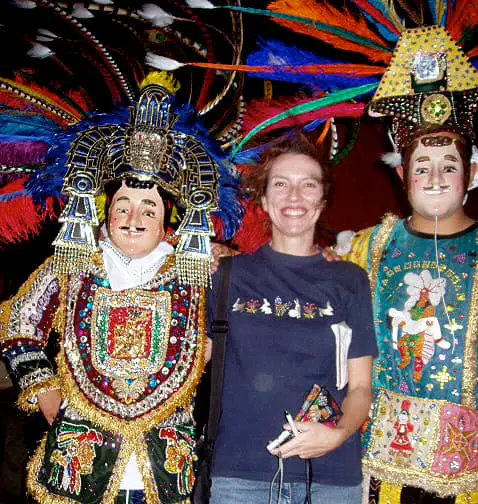

I also experienced some delirious days of Carnaval, enjoying Tlaxcala’s festival of costumes, dance, feathers, masks and whips that erupts in communities throughout the state in the run up to Lent.

But until the vision of Soltepec first loomed to my left on the highway, I wasn’t even sure whether Tlaxcala was a city or a state (it’s both).

My ignorance wasn’t unusual, and 10 years later, Tlaxcala state still receives less than 0.3% of Mexico’s tourists. About 95% of its visitors are nationals — most from the adjoining state of Puebla.

So last May, when attending Tianguis Turístico, Mexico’s international tourism trade fair, I strolled to Tlaxcala’s stand to find out ¿Qué onda?

I was both tickled and touched by the slogan that tourism authorities had chosen to promote their destination: Tlaxcala sí existe (Yes, Tlaxcala exists).

There are many reasons why Tlaxcala has gone unnoticed for so long, the most obvious being its struggle to find an image — let alone a voice — when under the shadow of the much richer and more powerful state of Puebla, which almost envelops it, bordering its little neighbor from both the north and south.

Furthermore, in the game of superlatives, while the state is home to the oldest church in Mexico and can boast some of the earliest colonial architecture and art, overstatement isn’t really Tlaxcala’s thing.

It is the proud home to Latin America’s first and only organic golf course (at the Hacienda Soltepec), and last year it made the Guinness World Records for achieving the longest sawdust carpet (3,939.53 meters) during the Noche Que Nadie Duerme festivities. But Tlaxcala’s allure is the deeper, uncommodified culture that is too intuitive to put your finger, let alone a marketing label, on.

The rhythm here is pueblerino; people are warm, but no one is in your face. The skyline stretches in all directions, with mountains of ever-changing cobalt, white, slate, purple and jade.

This is verified by visitors from France, Germany and Switzerland who have been quietly enjoying it without telling anyone else; it was surely no accident that the most enthusiastic tourists I saw at the foot of Malintzin last fall were two Oaxacan women in their 50s, both involved in hospitality in their home state. They were so impressed that they’d already planned their return with a coachload of other “conscious travelers” to stay for workshops in the eco-hotel Hacienda Santa Barbara the following month.

I would urge readers to get Tlaxcala-bound while the going’s good.

While it’s already too late for Tlaxcala’s Carnaval festivities this year — they ended on Feb. 21 — its distinctive annual celebrations are an example of the distinctive, highly memorable traditions the state has to offer the tourist looking for something a little off the beaten path.

Among Tlaxcala’s distinctive Carnaval traditions are the ancestral dances of the huehues —named after Huehueteotl, the Mesoamerican god of fire. Blending ancient pre-Hispanic customs with the imposed Christianity of the conquerors, they provide a glimpse of the religious syncretism that enlivens several Mexican festivities (the most famous now being Día de Muertos). These dances have been protected by the state, which declared them to be part of its intangible cultural heritage in 2013.

Some activities I recommend in Tlaxcala:

- The Hacienda Santa Barbara in Huamantla, which can be reached via its Facebook page or Instagram page, by emailing them at info@haciendasantabarbara.com.mx or by calling them at +52 246 196 2570. Here you can sign up for activities like a tortilla-making class and a massage.

- The Pulque Museum, Tlaxcala’s newest attraction, lovingly researched and curated. It’s open Friday to Sunday at the Hacienda Soltepec (https://www.haciendasoltepec.com/museo-del-pulque.php)

- The Organic Craft and Farmers Market, at the Hacienda Soltepec, open Saturday and Sunday. Find out more on their Facebook page.

My bet is that this little state, which for now asks only that its existence be acknowledged, could emerge into a kind of “new Oaxaca” — with some notable advantages: Tlaxcala is unafflicted by gentrification, blissfully free of spring breakers and is easy to get to (about two hours from Mexico City). It’s also slightly uncharted, so visitors can be surprised.

Tlaxcala’s inhabitants are friendly, it’s inexpensive and, refreshingly, it’s one of the safest places in the country. For more general info, try Tlaxcala’s state tourism website (in Spanish).

Barbara Kastelein has been a travel writer since 1997 when she began her first column “Travel Talk” for the Mexico City Times. She now divides her time between England and Mexico and is completing her fourth book “Heroes of the Pacific: The Untold Story of Acapulco’s Cliff Divers” (www.barbarakastelein.com)