The age of the filibusteros was a brief one, historically speaking. But it certainly hasn’t been forgotten on the Baja California Peninsula — where between 1850 and 1900, men referred to as “filibusters” made no less than four attempts to take over what are today the states of Baja California and Baja California Sur, in addition to several more attempts on the Mexican state of Sonora.

Of course, this was illegal. But for that brief 50-year period, a few ambitious men felt capable of conquering a country or region. What led to this delusion?

Several events inspired these small-scale wars. One was the example of Texas, which had achieved independence from Mexico through a settler revolt before becoming a U.S. state. Another was the Mexican-American War, in which Mexico lost over half its national territory, ceding all or parts of what are now nine U.S. states in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

Many of the filibusters were also men who had failed to get rich during the California Gold Rush and were looking for another opportunity to make their fortune. They had an economic motive, and in Manifest Destiny, they found their ideology.

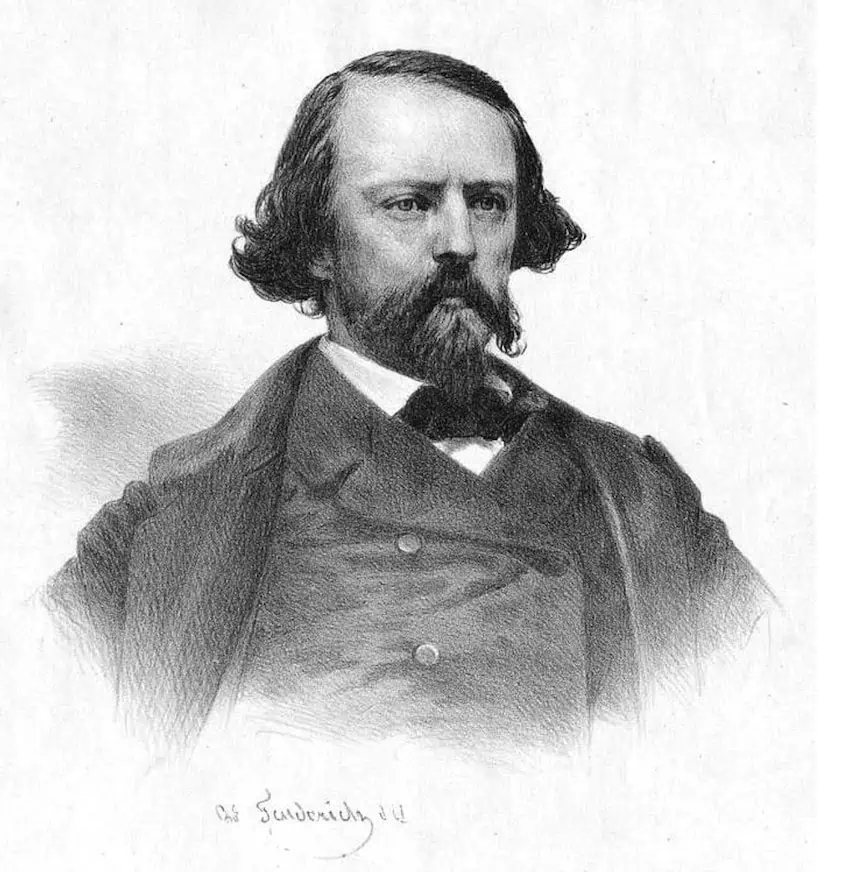

They also had a shining practical example: Count Gaston Raoulx de Raousset-Boulbon, an impoverished French aristocrat who failed in the gold fields before trying to take over the state of Sonora.

It did not end well for the count, but filibusters nevertheless saw it as a blueprint for their own actions.

Raousset-Boulbon and the 300 would-be colonists

Count Raousset-Boulbon’s first attempt to conquer Sonora in 1852 had a promising start. First entering the state under the guise of a settlement project authorized by the federal government, the count and his men took Hermosillo after a short battle. However, he was soon defeated at Guaymas and fled. But two years later, he decided to try again, setting sail from San Francisco with 300 would-be French colonists aboard the schooner Belle.

Their first stop was San José del Cabo in what is now Baja California Sur, where they were quickly beaten back, ending any peninsular designs. Thus chastened, Raousset-Boulbon and his men proceeded to Guaymas, the town on the coast of southwest Sonora they had failed to conquer two years earlier. Again, things did not go as planned. The French forces ultimately surrendered, and Raousset-Boulbon was shot by a firing squad in August 1854.

William Walker and the Republic of Sonora

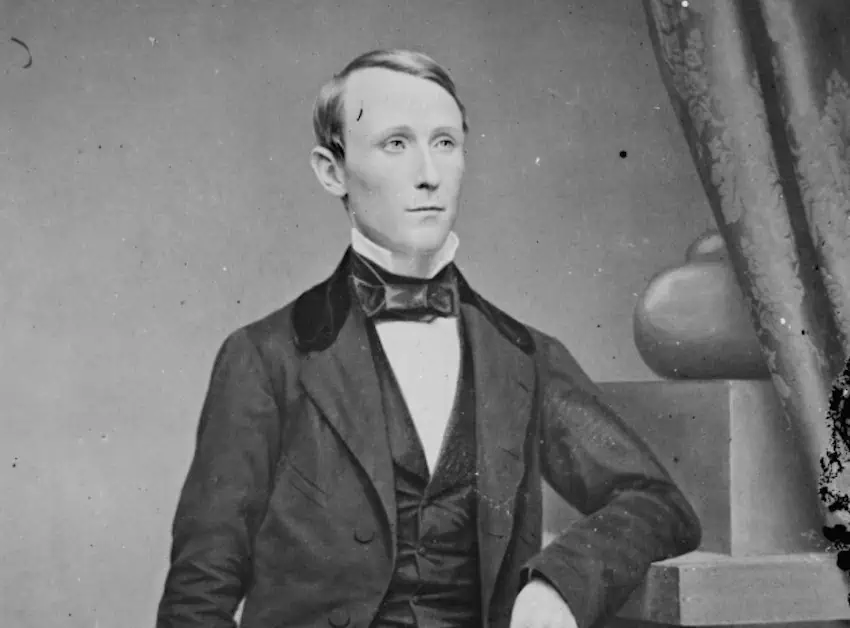

It’s hard to understand why William Walker, the most famous of the filibusters, would take Raousset-Boulbon’s failure in 1852 as an inspiration, but he did. Born in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1824, Walker was an educated man who practiced as a lawyer and a doctor. However, he was also a staunch pro-slavery advocate. He saw the Baja California Peninsula, once he conquered it, as another slave state that could be operated under the laws of the Code of Louisiana.

Walker’s ambition becomes perhaps more understandable considering that in 1851, the entire 760-mile peninsula had a population of only 7,000 people. Of course, he would have needed more than 45 men, the actual size of the army he had raised in San Francisco and sailed with in October 1853. But Walker was nothing if not optimistic.

His vision was for a Republic of Sonora that included the Baja California Peninsula and Sonora; in preparation, he had designed a flag and issued currency. After briefly landing at Cabo San Lucas, Walker and his small army proceeded to the capital, La Paz, where, surprising the locals, they seized both the outgoing and incoming jefes político, an office then equivalent to governor.

Emboldened, the filibusters looted the houses of better appearance and proclaimed their new slave state. However, opposition forces under two Mexican-American War veterans, Manuel Pineda and future general Manuel Márquez de León — the man for whom the city’s airport is now named — soon forced a retreat to Cabo San Lucas, where Walker and company were further harassed by local militia led by the legendary Ildefonso Green, remembered today with a street and neighborhood designation in the Land’s End city.

Thus repulsed, Walker and crew sailed to Ensenada, appropriating a ranch and receiving 150 reinforcements, a much-needed boost enabling them to hold off the local resistance for a few months before desertion and deaths led to the final retreat.

“So ended the last battle of the Republic of Sonora,” wrote Irish-American poet James Jeffrey Roche in “By-Ways of War,” a 1901 history of the filibusters. “Four and thirty tattered, hungry, gaunt pedestrians, whimsically representing in their persons the president, cabinet, army and navy of Sonora, marched across the line and surrendered as prisoners of war to Major McKinstry, U.S.A., at San Diego, California.”

Walker was not discouraged by his defeat and next decided to conquer Nicaragua. That did not end well, either, although he succeeded briefly. Forced out of the country, he was ultimately executed for piracy and filibusterism by a Honduran firing squad in 1860.

A worse Napoleon in La Paz

By the mid-1850s, officials across the Baja California Peninsula were alert and ready for further filibustering expeditions.

Jean Napoleon Zerman, undoubtedly the lesser of the 19th-century Napoleons, sailed into the bay of La Paz in 1855 with three ships — two flying American flags, the other none — wearing a uniform of mismatched parts and a sombrero embellished with chicken feathers. Pablo L. Martínez, in his “Historia de Baja California,” notes that the would-be admiral’s letters contained “various absurd decrees, written in barbarous Spanish.”

Zerman claimed to have official backing from Juan Álvarez, the independence hero who had briefly been president of Mexico in 1855. However, locals did not accept this authorization, and Álvarez later denied giving it. Shots were fired, with one of Zerman’s men killed before his ships and weapons were confiscated. Was he really a filibuster? Zerman was Italian by birth, a veteran of the French navy, and 64 of his 65 men were foreigners. Also, his ships were outfitted with two cannons. But he was freed after two years of imprisonment and left the country unharmed.

In that, he was fortunate. Two years later, former California senator Henry Crabb, who had tried to enlist with Walker, invaded Sonora with 100 men. After a six-day siege at Caborca, Crabb, like Raousset-Boulbon, was executed for his crimes, although only the Californian of the bunch had his head cut off and preserved in vinegar — or possibly mezcal; sources differ on this point.

San Diego newspaper editors try to take Baja with a ruse

The last and silliest of the 19th-century filibuster schemes was cooked up by San Diego newspapermen, including Walter Gifford Smith, editor of the San Diego Sun; B.A. Stephens, editor of the San Diego Informant; and Captain John F. Janes, who published the San Pedro Shipping Gazette. Funding, however, was courtesy of the English-owned Mexican Land and Colonization Company. The latter provided US $100,000 for the plot, thinking U.S. ownership of the Baja California Peninsula would send real estate prices soaring.

Like many modern-day Baja ventures, this was all about real estate. According to “The Filibusters of 1890,” edited by California historian Anna Marie Hager, the plan called for the local military to be overpowered, while presumably drunk, following a fandango at the Hotel Iturbide in Ensenada. This attack would be accomplished by filibusters arriving aboard the steamships Carlos Pacheco and Manuel Doblan, who could also help to capture the Mexican warship Democrata, which would inevitably arrive soon after.

However, the plan came to naught. Indeed, it was never even implemented after being leaked to the public by a rival newspaper. That was likely for the best for the plotters, and certainly so for the residents of the Baja California Peninsula. After half a century of takeover attempts, they’d had enough.

Chris Sands is the Cabo San Lucas local expert for the USA Today travel website 10 Best, writer of Fodor’s Los Cabos travel guidebook and a contributor to numerous websites and publications, including Tasting Table, Marriott Bonvoy Traveler, Forbes Travel Guide, Porthole Cruise, Cabo Living and Mexico News Daily. His specialty is travel-related content and lifestyle features focused on food, wine and golf.