Crème brûlée is a classic, familiar dessert made of custard topped with hard, caramelized sugar. It sounds French, but the English were the forerunners with a similar dessert that they dubbed “burnt cream.” The French joined the club in 1691, when crème brûlée first appeared in Massialot’s cookbook, “Cuisinier royal et bourgeois.” He caramelized the sugar using a red-hot shovel. Crème brûlee, most notably, is as far from traditionally Mexican a dessert as it might be possible to be.

So, who would have thought of teaming a dull, sweet custard (and yes, it’s good!) with Mexican ancho chili, chocolate and cinnamon to give it a kick? I don’t know but the question triggered another in my mind. Why do Mexicans like their food so spicy? The answer may surprise you.

Chili peppers contain a compound called capsaicin. The chemical triggers a burning sensation on the tongue which is countered by the brain releasing endorphins and increasing the body’s level of serotonin. In other words, eating hot chilis makes you feel good, along with giving you a sense of well-being — and the sensation can be addictive. Some even consider Mexicans to be masochists because of their love of eating these hot peppers to experience “pleasure through pain.”

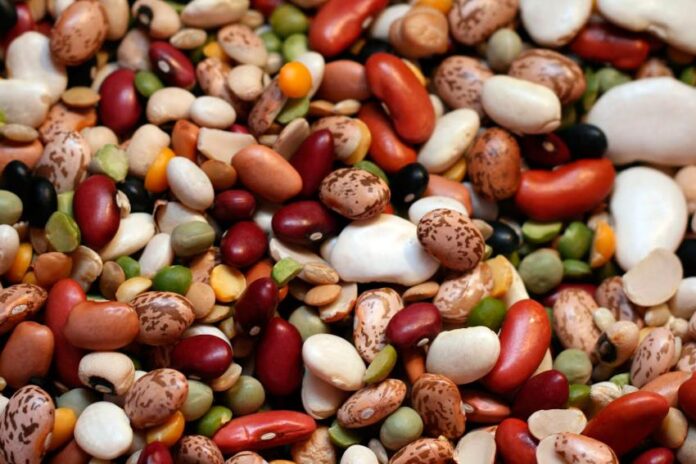

Chilis have been a part of Mexican culture and cuisine since pre-Hispanic times, and the ancho chili traces its history to Puebla, in Central Mexico. They are known for their rich, mild, and sweet flavors making them perfect for salsas and moles, and with today’s recipe: dessert! They are noted for their high Vitamin C content and are the most widely used chili pepper in Mexico. In the U.S., they gained prominence in Tex-Mex cuisine and became popular with the advent and spread of Mexican food.

Now what if we teamed that dull, “burnt cream,” custard with a Mexican ancho chili and some Mexican chocolate and cinnamon? I’d say we’d have a rich, unique feel-good crème brûlée that’s perfect for any occasion, whether it’s dinner for two or that elegant dinner party you’ve been planning. Here’s the recipe.

Chocolate-ancho chili crème Brûlee with cinnamon whipped cream:

Ingredients:

- 3 Cups (720 ml) whipping cream (crema de batir)

- 1 cinnamon stick (rama de canela)

- 1 dried ancho chili with seeds, stemmed, chopped into 10-12 pieces (chile ancho seco)

- 1/2 Cup sugar (azúcar estándar)

- 1 Cup bittersweet chocolate chips (chispas de chocolate agridulce, about 70% cacao)

- Use dark chocolate that is about 70% cacao, cut into small pieces, if you can’t find bittersweet chocolate chips.

- 6 large egg yolks (yemas de huevo)

- 1/2 tsp. ground cinnamon (canela molida)

- 6 TBS. sugar (azúcar estándar)

Instructions:

- In a medium saucepan, over medium heat, add cream, cinnamon stick and ancho chili.

- Heat until small bubbles form around the edges of the pan. Remove from heat.

- Add chocolate chips and stir until combined and smooth.

- Let custard mixture cool to room temperature.

- Using a mesh strainer, push custard through, discarding the cinnamon stick, chili, and seeds.

Next:

- Preheat oven to 275°F/135C

- In a medium bowl, whisk egg yolks briskly until pale in color, about 1-2 minutes.

- Whisk in ½ Cup sugar until dissolved, about 2 minutes.

- Gently whisk in cream; do not overbeat. (Do not let bubbles form.)

Next:

- Place 8 crème brûlée dishes in a baking pan.

- Divide the custard mixture evenly between 8 dishes, leaving about a 1/2’’ at the top of the dish for the sugar topping, which is added later.

- Place the pan in the oven and gently pour in 4-5 cups of warm water (enough to come halfway up the sides of the dishes).

- Bake in oven for 30-40 minutes, or until the center of each custard still jiggles slightly.

- Remove the dishes from the pan by pulling the oven rack out and lifting the dishes from the hot water.

- Let cool until room temperature, about 15 minutes.

- Refrigerate at least 2 hours or up to 2 days.

Cinnamon Whipped Cream:

Ingredients:

- 1 Cup (240 ml) whipping cream (crema de batir)

- 2 TBS. sugar (azúcar estándar)

- Dash of cinnamon (canela molida)

Instructions:

- Using an electric mixer, beat whipping cream, sugar and cinnamon until stiff peaks form.

- Refrigerate until ready to serve with crème brûlée.

To Serve your Mexican Crème Brulee:

- 20-30 minutes before serving mix together ½ tsp. of cinnamon and 6 TBS. of sugar.

- Sprinkle 1 TBS. of sugar mixture over each custard.

- Using a hand-held torch, about ½ inch from sugar, caramelize the top by slowly working around the entire brûlée. Then torch it entirely.

- Return to the fridge for 10-12 minutes to chill the brûlée.

- Top with Cinnamon Whipped Cream and serve.

Disfruta!

Deborah McCoy is the one-time author of mainstream, bridal-reference books who has turned her attention to food, particularly sweets, desserts and fruits. She is the founder of CakeChatter on Facebook and X (Twitter), and the author of four baking books for “Dough Punchers” via CakeChatter (available @amazon.com). She is also the president of The American Academy of Wedding Professionals.