Energy may be the most foundational pillar behind everything we’ve discussed so far: re-industrialization, nearshoring, AI and North American competitiveness. You don’t run factories, servers or supply chains without reliable, scalable and affordable power. Energy isn’t a side story — it’s the operating system of modern economic activity.

Mexico’s role in this system is often framed through an outdated oil lens.

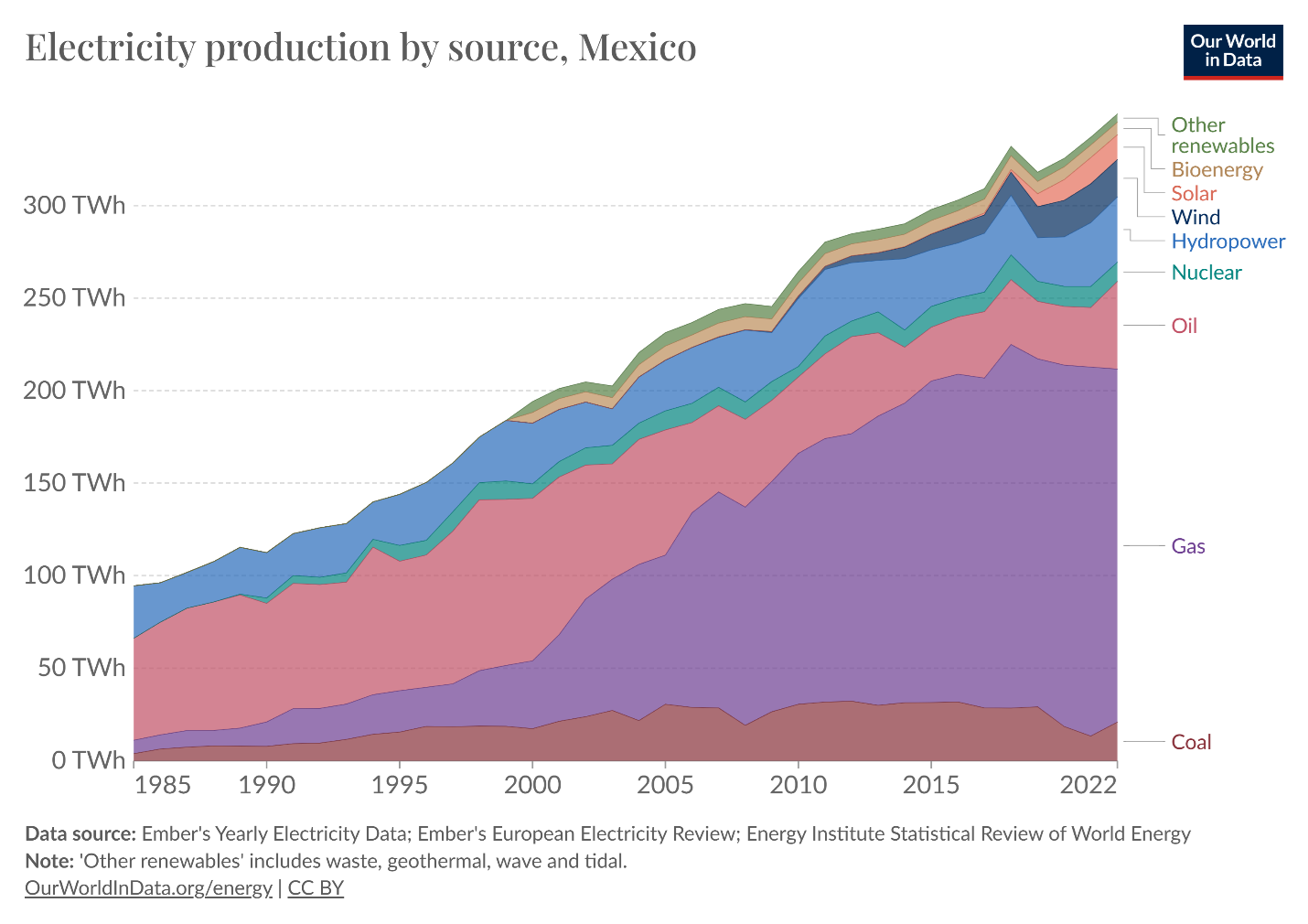

Forty years ago, that framing made sense. In 1982, Mexico exported roughly $24 billion, and almost 65% of that was crude oil. Today, Mexico exports more than $620 billion, with oil representing just 3.5% of the total, while manufacturing accounts for nearly 90%. In other words, Mexico’s economy has transformed from being oil-dependent to manufacturing-driven — and manufacturing is, above all, energy-intensive.

This transformation has tied Mexico and the United States together through energy flows that are structural, not optional.

Natural gas: The backbone of integration

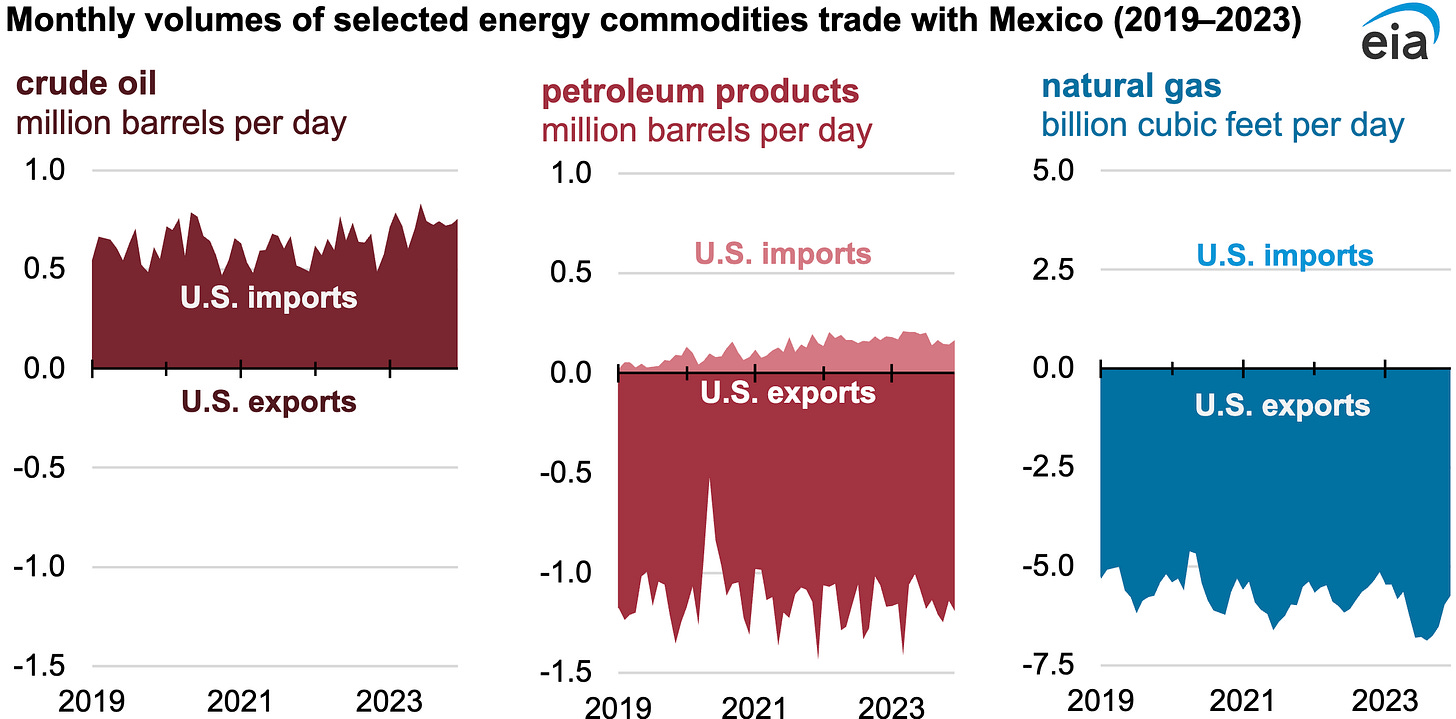

Mexico is the largest export market for U.S. natural gas. Over the past decade, pipeline exports from the United States to Mexico have surged. By early 2024, Mexico was importing roughly 3.1 billion cubic feet per day of natural gas, with more than 60% of its total consumption supplied through pipeline imports from the United States. Natural gas now anchors Mexico’s electricity generation, industrial production and export manufacturing — much of which directly supports U.S. supply chains.

Looking only at imports, the integration is even clearer: virtually all of the natural gas Mexico imports — over 99% — arrives via pipeline from the United States, reflecting a high degree of physical and commercial interdependence between the two energy systems, particularly U.S. producers in Texas, for whom Mexico has become a critical and stable export outlet.

Natural gas now anchors Mexico’s electricity generation, industrial production, and export manufacturing — much of which directly supports U.S. supply chains.

Refined products & crude: A circulatory system

Energy flows are not one-way. U.S. refineries maintain a strategic relationship with Mexico as a crude oil supplier. In 2024, they imported 169.9 million barrels of Mexican crude, accounting for roughly 7% of total U.S. crude imports. In turn, those refineries export gasoline, diesel, and petrochemicals back into Mexico.

The result is clear: under many trade measures, the United States now runs an energy surplus with Mexico, meaning the value of U.S. energy exports to Mexico exceeds the value of Mexican energy exports to the U.S. This surplus supports U.S. GDP, sustains jobs in energy production and refining, and strengthens America’s position in global energy markets.

Data source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, U.S. Imports by Country of Origin, Exports by Destination, U.S. Natural Gas Imports by Country and U.S. Natural Gas Exports and Re-Exports by Country.

Mutual benefits embedded in infrastructure

From the U.S. perspective, Mexico acts as a stable outlet for U.S. natural gas production. That matters because U.S. producers — particularly in the Permian Basin — face domestic pipeline constraints and limited LNG export capacity. Mexico’s demand absorbs incremental supply, supporting upstream investment, drilling activity and workforce utilization even when global markets are volatile.

As documented by the U.S. Energy Information Administration, this integration is neither temporary nor marginal. Pipeline shipments of U.S. natural gas to Mexico have increased by an order of magnitude since the early 2000s, and today the majority of U.S. pipeline exports flow south of the border rather than overseas.

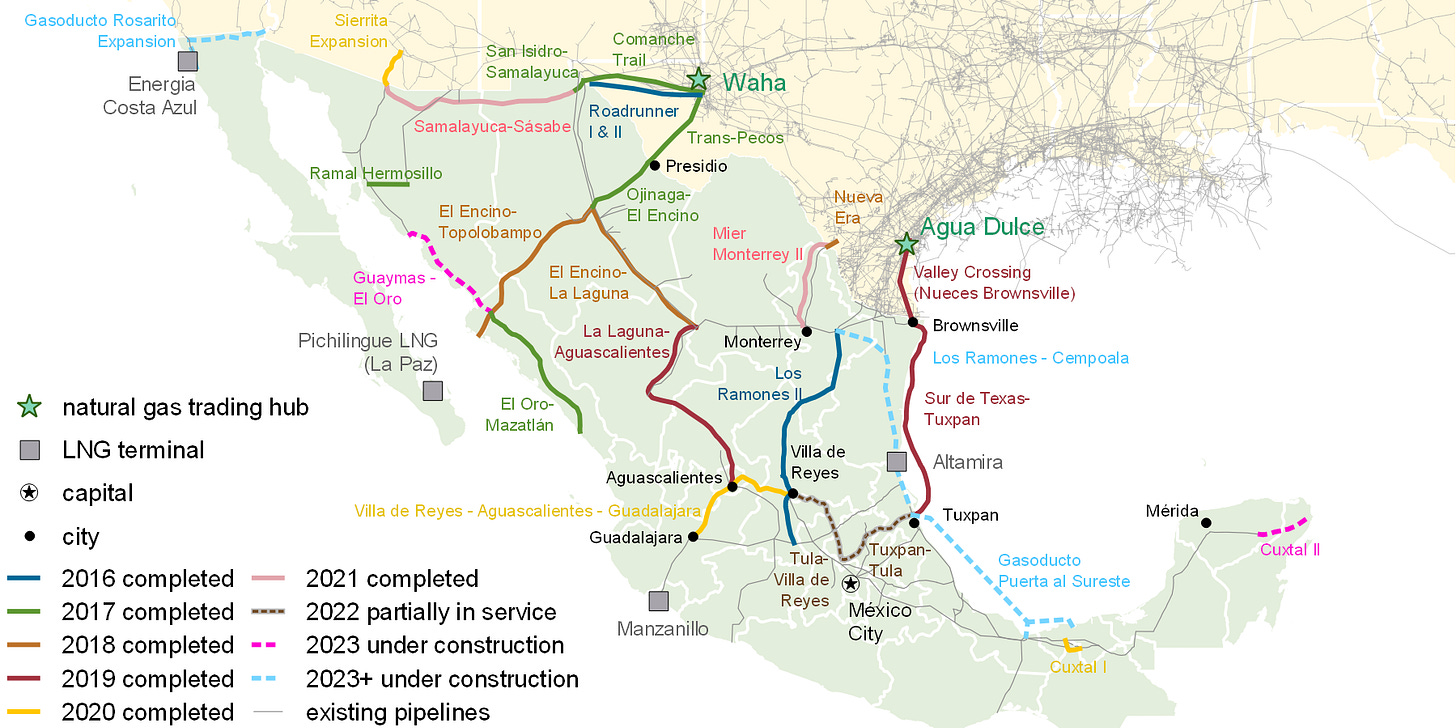

U.S.-Mexico Border Crossing Natural Gas Pipelines and Expansions of Mexico’s Domestic Pipelines

Data source: U.S. Energy Information Administration and Comisión Nacional de Hidrocarburos, Mexico. “U.S. natural gas pipeline exports to Mexico have grown in recent years as the domestic pipeline network within Mexico continues to expand.”

Why policy certainty matters

The United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) plays a strategic role by providing investment certainty for cross-border energy infrastructure — pipelines, terminals and long-term contracts. Without that legal and institutional framework, it becomes far more difficult for energy companies to commit capital to multi-decade projects that underpin factories, grids, and industrial parks on both sides of the border.

This is why energy policy cannot be an afterthought in debates about economic strategy or geopolitical competition. Mexico is not peripheral to U.S. energy security — it is central to it. American energy production, refining, and export capacity are increasingly linked to Mexican demand, infrastructure, and industrial growth. Likewise, Mexico’s ability to sustain its manufacturing base and capture nearshoring opportunities depends on continued access to U.S. energy and predictable investment conditions.

If the United States wants to remain an energy powerhouse, it cannot do so alone. It’s not just about drilling in Texas or New Mexico — it’s about smart partnerships, strong trade frameworks and working closely with reliable neighbors.

Seen this way, energy fits naturally with the other themes in this series. If AI is the brain of the future economy, energy is the bloodstream. And today, that bloodstream flows across North America.

Catch up on parts 1-5 of Could Mexico make America great again? here:

- Part 1: An introduction

- Part 2: A primer on China

- Part 3: Zeroing in on the demographics

- Part 4: About that trade deficit

- Part 5: How the AI race changes the game

Pedro Casas Alatriste is the Executive Vice President and CEO of the American Chamber of Commerce of Mexico (AmCham). Previously, he has been the Director of Research and Public Policy at the US-Mexico Foundation in Washington, D.C. and the Coordinator of International Affairs at the Business Coordinating Council (CCE). He has also served as a consultant to the Inter-American Development Bank.