I think 2024 is going to be a significant year for Mexico, so I’m going out on a limb to make some predictions for this year.

Below you’ll find my 17 predictions of the top news stories in Mexico this year. Please note that I am not expressing an opinion on whether these are good or bad things to come, but just my best guess at what will dominate the headlines.

- The nearshoring boom will continue to accelerate and Mexico will receive a record amount of foreign direct investment.

- One if not two Chinese auto companies will announce massive plant investments in Mexico.

- Increased discussion and tension will arise among USMCA partners (U.S., Canada, Mexico) over the rapidly increasing Chinese investment and imports into Mexico.

- The NBA will confirm that an expansion team will come to Mexico City.

- Claudia Sheinbaum will win the presidential election in a landslide.

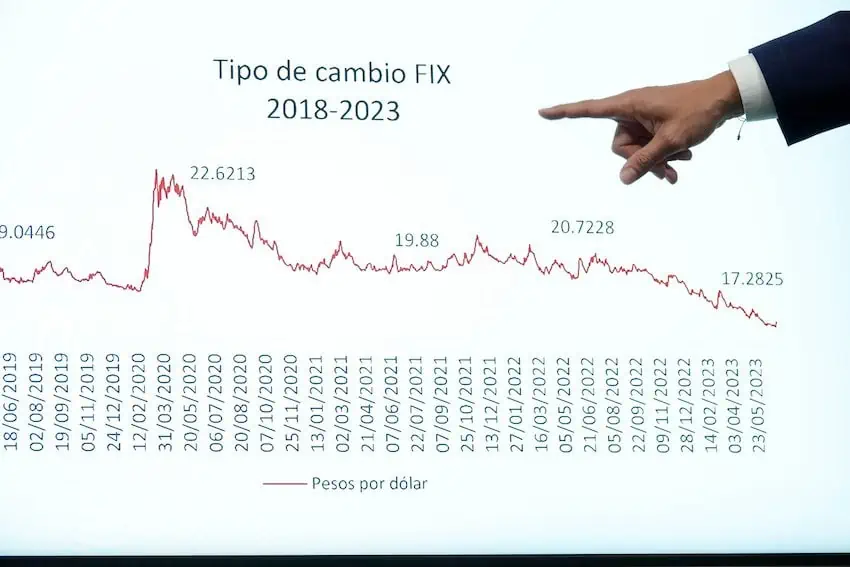

- The Mexican peso will not move significantly in reaction to the election results (as it often does).

- The Maya Train project will be more positively viewed by the end of the year and increasingly be recognized as a strategically important investment for the region.

- The Tulum airport will receive a surprisingly high number of new flights and become a major flight destination.

- The Isthmus of Tehuantepec train will get increased interest and attention due to continued problems with the Panama canal.

- Mexico will become an increasingly important topic in the upcoming U.S. elections. Issues like immigration, fentanyl, and drug cartels will cause some candidates to threaten significant actions against the country.

- Despite the campaign rhetoric, Mexico will increase its lead and share as the largest trading partner of the United States.

- Tesla will accelerate its plant investment in Monterrey.

- The number of U.S. and Canadian citizens moving to Mexico will continue to accelerate.

- A record number of international tourists will come to Mexico.

- The Bank of Mexico will finally begin to lower interest rates in the first quarter of the year, which should weaken the peso gradually.

- The Mexican peso will end the year above 18 to the US dollar.

- Mexico will end 2024 as the 10th largest economy in the world (moving up 2 places from 2023 and 4 places from 2022).

What do you think? How many of my predictions do you agree or disagree with? In the spirit of dialogue and debate, I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments.

Travis Bembenek is the CEO of Mexico News Daily and has been living, working or playing in Mexico for over 27 years.