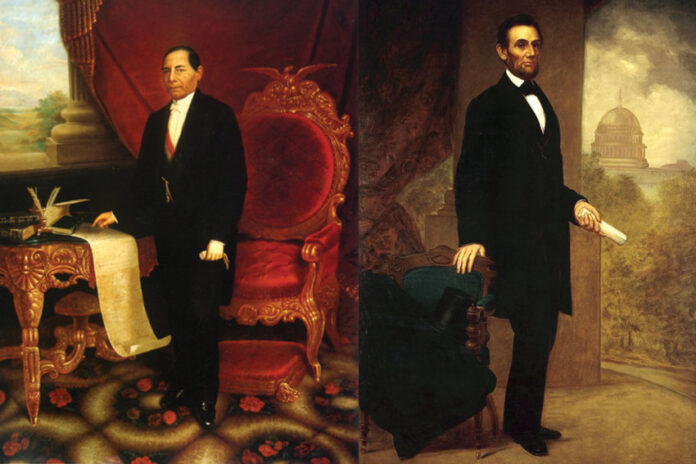

March of 1861 saw the inauguration of two of the most impactful presidents both Mexico and the United States would ever have: Benito Juárez and Abraham Lincoln.

In Mexico, the Reform War had come to a close with the Liberal victory of December 1860, but the country was devastated and the Conservative Party had lived to fight another day. In the United States, North and South were on the verge of civil war, and seven states had seceded from the Union by the end of February.

Lincoln, who had followed a losing 1858 campaign for the U.S. Senate by winning the country’s highest office in 1860, did not hear from one European leader when he won the presidency. He had never traveled outside of the United States. So Lincoln had never been to Mexico, and it is unlikely he had ever met a Mexican at all until one fateful snowy day in January 1861.

A Mexican diplomat befriends the Lincolns

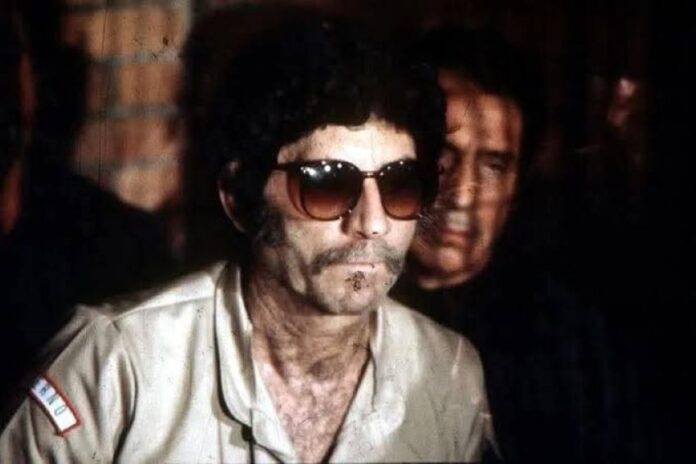

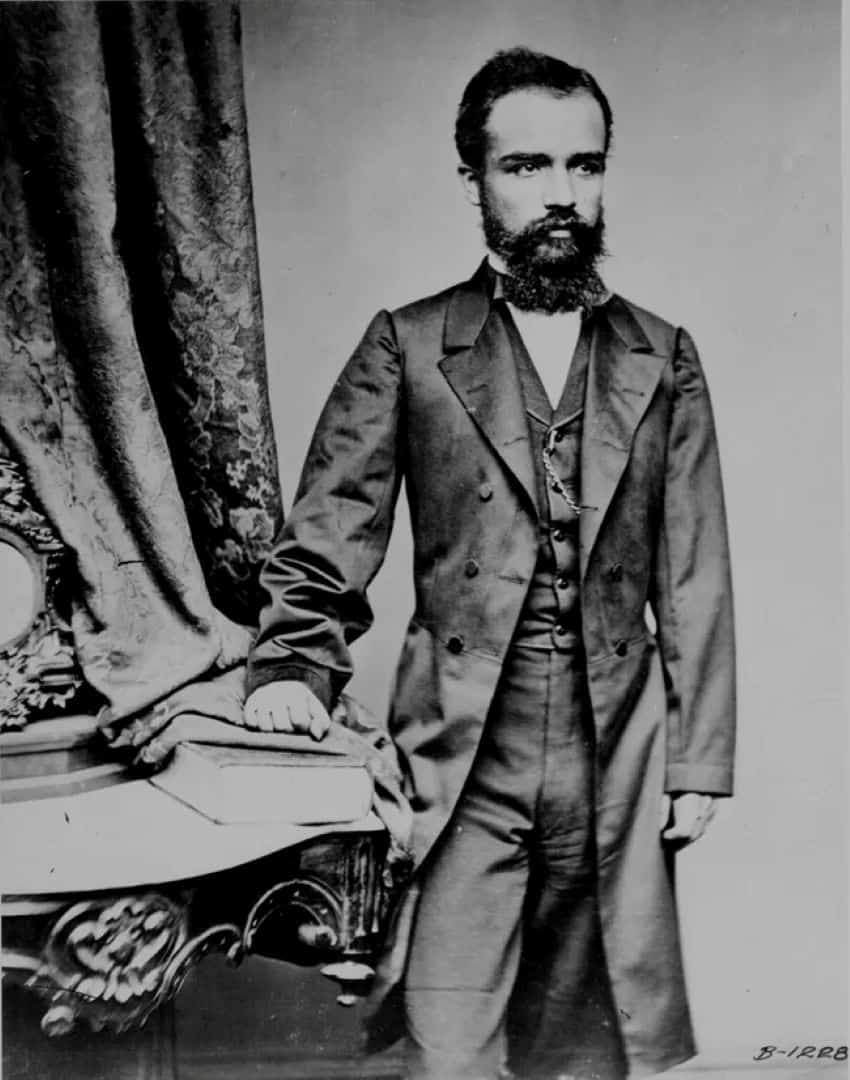

At the time of Lincoln’s inauguration, Matías Romero had been working at the Mexican Legation in Washington, D.C. for a year. In January 1861, the savvy and ambitious young diplomat and future Mexican Treasury Secretary received a letter that said, “It is the wish of the President [Juárez] that you proceed to the place of residence of President-elect Lincoln and in the name of the government, make clear to him in an open manner, if the opportunity presents itself, the desire which animates President Juárez, of entering into the most cordial relations with that government.”

Romero sent Lincoln a letter of congratulations on his election. Lincoln acknowledged the letter and expressed his best wishes for “the happiness, prosperity and liberty of the people of Mexico.” With his government’s instructions in hand, Romero set off for Springfield to meet and personally congratulate the newly elected president. Romero was probably the first Mexican Lincoln had ever met, although his support of Mexico went back to 1846, leading Juárez to believe he could forge friendly relations with the Republican.

Abraham Lincoln opposed the Mexican-American War

As a young congressman from Illinois, Lincoln opposed President James K. Polk’s 1846 invasion of disputed territory in Texas, which started the Mexican-American War, but there was strong patriotic fervor in the country, and many supported Polk’s expansionist plans. Lincoln was not opposed to territorial expansion but opposed to the expansion of slavery. He also respected Mexico’s sovereignty and thought the U.S. should have a good relationship with its southern neighbor.

He accused Polk of using a falsehood to justify a war. After a skirmish in the disputed territory of what is now southern Texas, Polk declared, “American blood has been shed on American soil,” and as a result, a state of war existed with Mexico.

Lincoln introduced the first of eight resolutions opposing the war. The first questioned the war’s constitutionality and challenged war proponents to show him the “spot” where blood had been shed. His resolutions became known as the “spot resolutions,” and people called him “spotty Lincoln.” His opposition to the war was so unpopular with his constituents in Illinois that he decided not to run for reelection.

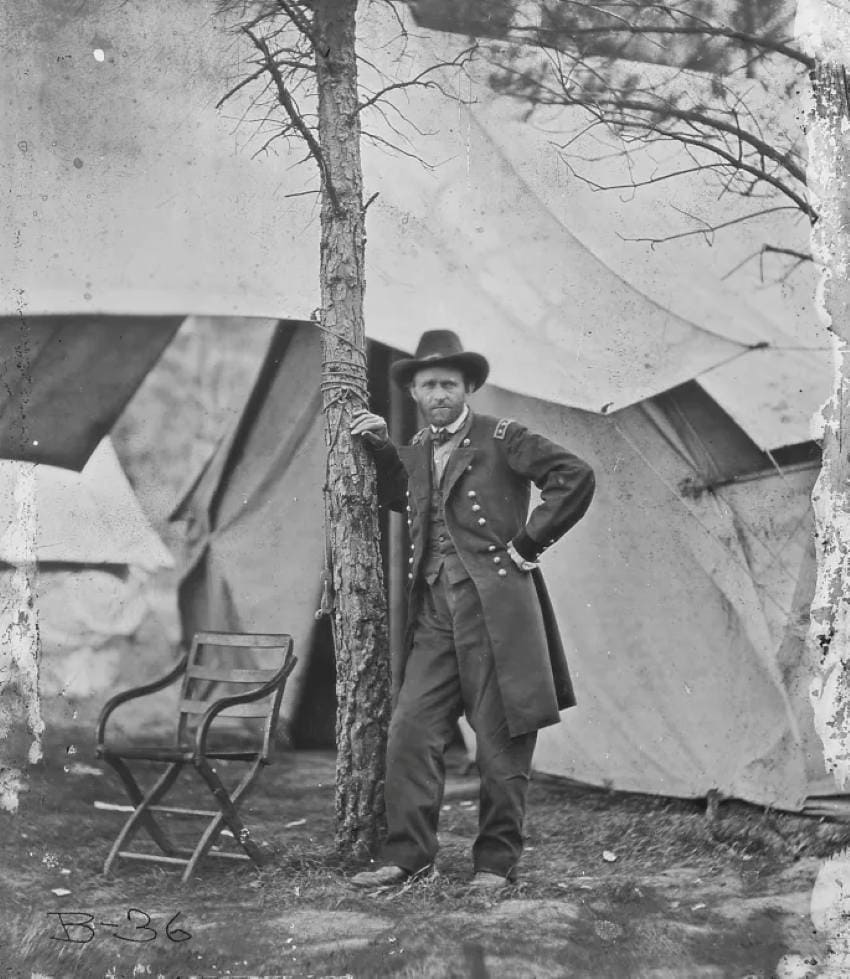

Lincoln was not the only prominent American opposing the war. John Quincy Adams and Henry David Thoreau openly challenged the war effort. Ulysses S. Grant, who served in the war, said in his memoirs that it had been, “the most unjust war ever waged against a weaker nation by a stronger.” The United States won the war and increased its territory by 750,000 square miles, reducing Mexico’s territory by half.

Romero began the meeting by briefing Lincoln on the situation in Mexico: The new President Benito Juárez had assumed leadership of a country devastated by civil strife, whose treasury was depleted. But Juárez believed Lincoln was predisposed to a friendship between the two countries. The Romero papers, preserved at the Banco Nacional de México, indicate that the conversation went well and Lincoln was taken with the young diplomat.

During the War of Independence, Mexico had acquired a great deal of foreign debt. French Emperor Napoleon III sought a foothold to challenge the United States’ dominance in the Americas and planned to use Mexico’s debt to France as a pretext to invade the nation and establish a colonial empire.

Mexico wanted economic cooperation with the U.S. and to be treated as a respected southern neighbor. Perhaps most importantly, the Mexican administration counted on Lincoln to respect Mexico’s sovereignty.

Romero nurtured a personal relationship with the U.S. president and the First Lady, Mary Todd Lincoln, and the Union generals Ulysses S. Grant and Philip Sheridan, which would prove very helpful in Mexico’s struggle against the French. Lincoln was grateful to Romero because he would accompany the First Lady on her frequent shopping trips, freeing Lincoln from a responsibility he was happy to relinquish.

US support for Mexico’s war with France

The United States did not officially recognize the French regime in Mexico but remained neutral in the war. However, the U.S. needed Mexican troops to slow the French advance to the border, where the French planned on providing the Confederacy with more advanced weapons. The resourceful Romero used Lincoln’s acknowledgment letter from their first meeting and his friendship with Lincoln and Grant to raise US $18 million from prominent bankers to support the Mexican troops. Grant helped him secure Springfield rifles, considered superior weapons.

In 1863, the French took Mexico City and installed an Austrian archduke, Ferdinand Maximilian, as Emperor Maximilian I. Mexico needed more arms from the United States.

After the U.S. Civil War ended, Grant covertly sent 50,000 troops to the border under General Sheridan, instructing them to conveniently lose 30,000 rifles that could be “found” by the Mexican troops. By 1867, the French had withdrawn from Mexico and Juárez had triumphed. The Mexican Republic was restored, although Lincoln didn’t live to see it.

Lincoln revered in Mexico

Lincoln’s courageous stand against the Mexican-American War and his support of Benito Juárez (sometimes referred to as the Abraham Lincoln of Mexico) endeared him to the Mexican people. His support of political equality, economic opportunity and opposition to slavery demonstrated that he shared their values.

Some historians believe that had Lincoln lived, the two leaders would have forged a close alliance between the United States and Mexico in economic and cultural matters. Some historians say they could not have had a close relationship because they never met and no correspondence between them has been found. However, it is assumed that Romero, as a diplomat, would have carried messages between the two leaders, and there is evidence in Romero’s papers that he conducted a dialogue between the two.

If you have been to Mexico City — among all the statues commemorating Mexican historical figures and events — you may have been surprised to come across a statue of Abraham Lincoln. This statue in Parque Lincoln is identical to the one in London’s Parliament Square (The original stands in Lincoln Park in Chicago).

Numerous Lincoln statues are in Mexico, including one towering over Tijuana’s grand boulevard, Paseo de Héroes, and one in Ciudad Juárez. There is also a statue of Juárez in Washington, D.C.

On April 15, 1966, President Lyndon Johnson dedicated the Abraham Lincoln statue in Mexico, symbolizing the friendship between the two countries. And on October 26, 1967, Mexican President Gustavo Ordaz reciprocated by dedicating the statue of Juárez in Washington, D.C.

Sheryl Losser is a former public relations executive, researcher, writer and editor. She has been writing professionally for 35 years. She moved to Mazatlán in 2021 and works part-time doing freelance writing. She can be reached at AuthorSherylLosser@gmail.