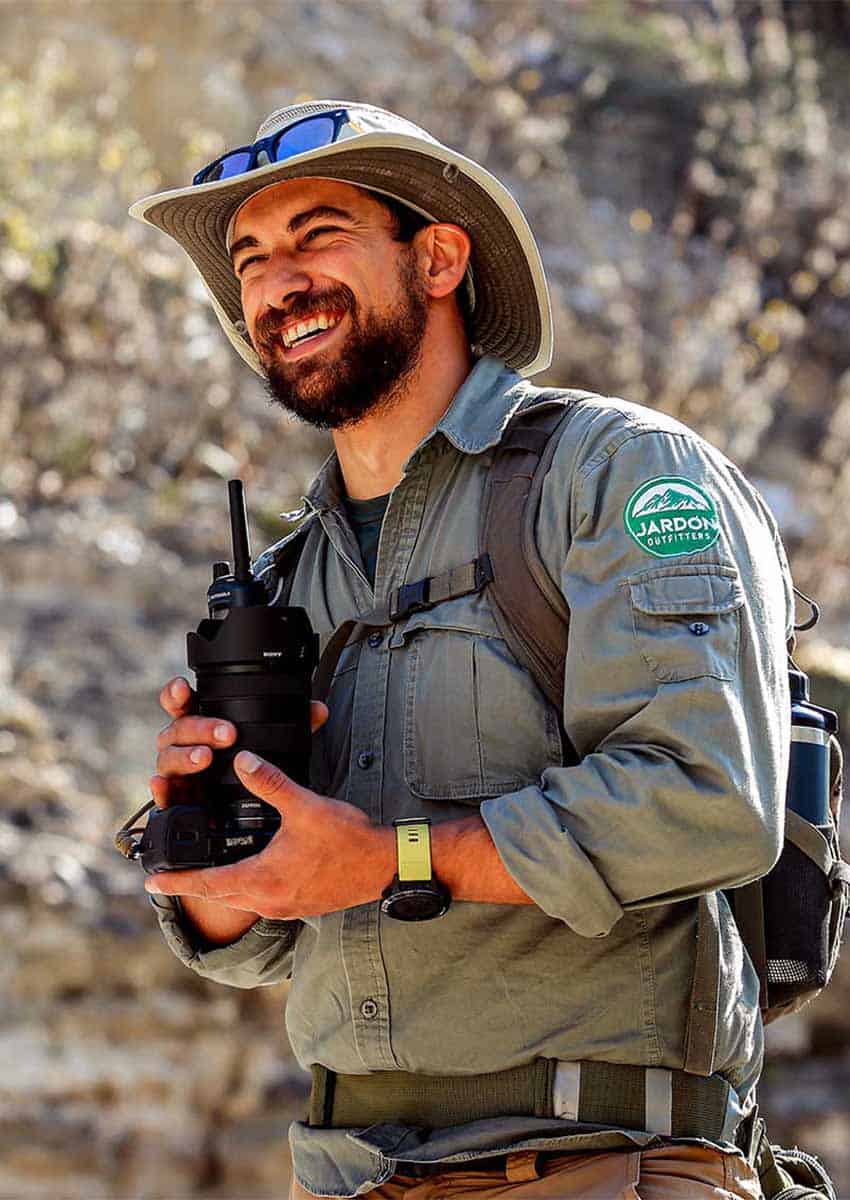

Cesar Menchaca puts the work of Wixárika (Huichol) artists in spaces it might never otherwise be.

Born in 1967 in Mexico City, Menchaca defines himself not as an artist or anthropologist, but as “an entrepreneur-lover of art and Mexican culture.”

That love can be seen in the works and exhibitions of his Menchaca Studio, established in 2010 in part of his home.

The organization’s mission statement says that the goal is to “create artistic pieces with high cultural value by fusing Mexican art of all types with contemporary art.” The studio succeeds most with eye-catching reinterpretations of Wixárika art, but they and similar reworkings of traditional Indigenous art can raise questions.

Menchaca’s involvement in the field is relatively recent: born to a family of 14 in one of the downtrodden neighborhoods surrounding the Virgin of Guadalupe Basilica in Mexico City, he worked his way out of poverty.

His journey began in fashion, founding brands like ¡Qué Chingón!, which had some success exporting to the U.S. But textiles is a fickle business, and pressure from Chinese clothes makers bankrupted him by 2010.

Around this same time, he became attracted to Wixárika art because he saw “for just how little the artisans had to sell their work out on the street,” and he knew he could develop a much better market.

Although Menchaca is a self-taught artist, he does not get involved in the creative process. His main talent is pairing contemporary and Wixárika artists affiliated with his studio to create works for high-profile international audiences.

The studio is a major promoter of Wixárika beadwork worldwide — its work has been displayed in the Americas, Europe, the Middle East and Asia in famous luxury hotels, skyscrapers and sporting events. At the Burj Khalifa, the studio exhibited a bronze Mexican eagle studded with 3 million Swarovski crystals. The Sport Summit Mexico Exhibit received a soccer ball with 3.8 million beads.

Menchaca has also done works for the NFL, Formula 1, Longines Global Champions Tour México, the Russia 2018 Soccer World Cup and the Hotel Presidente International. He has even collaborated with Cirque du Soleil in Montreal and various other corporations to decorate watches, wine bottles and more.

In Mexico, his work has been exhibited at the Palacio de Bellas Artes and Paseo de la Reforma in Mexico City. A retrospective exhibit called “Pasiones” (Passions) has been touring Mexican cities.

The works are aimed at audiences that would probably never give Wixárika work a second (or even a first) glance. Themes vary widely, but most relate to Mexico in one way or another. But the purpose here is not an authentic recreation of Wixárika culture or art, nor is it to educate the public about either in any depth. At most, the pieces function as a kind of introduction to Mexican culture, and with luck, some will read the labels and learn the words Wixárika or Huichol.

Although those who place the beads are Wixárikas from western Mexico, there can sometimes be very little from that culture in the design or execution. The base sculpture is made from resin, bronze, carbon fiber and brass, while the beads are fastened with modern adhesives. Such materials are far more durable than the traditional wood and Campeche wax.

In about the past decade, Menchaca estimates, his collaborations have placed more than 150 million beads and other tiny objects. Some projects have used crystals (including the aforementioned Swarovski), sequins, and for one project, bits of plastic recovered from ocean-dumped garbage.

In the choices of form and decoration, primary attention is paid to making works that draw attention. Wixárika elements can be secondary or even nonexistent.

Reinterpretations, especially those with significant or controlling interest by non-Indigenous people, risk significant criticism. There needs to be a balance between two competing, even contradictory goals; respecting the originating culture (avoiding kitsch) and creating art that the market will accept.

All Mexican folk art faces the same pressures to change to meet market conditions, but Wixárika art has an added issue: its elements have religious meaning.

“For the Huichol, art is prayer and direct communication with and participation in the sacred realm,” said Peter Furst, an early researcher and author of “Visions of a Wixárika Shaman.”

“[Art] is meant to assure the good and beautiful life; health and fertility of crops, animals, and people; prosperity of the individual, the kin group, and the larger society,” Furst says.

The studio is by no means the first or only organization to reinterpret Wixárika art and broaden its appeal. Depending on your point of view, projects like these are a bridge between cultures, cultural appropriation or maybe a bit of both. The issue of how, how much, and even whether traditional works should be modified at all continues to be debated.

Changing attitudes have led to efforts to establish “communal rights” over traditional art and designs in Mexican law, although its successful implementation is in doubt — and what this might mean for the studio remains unclear.

Menchaca is certainly aware of the issues surrounding his work but defends it, saying that even if the sculpture is of a very “non-Mexican” endangered rhinoceros “… it also represents the similar danger [of disappearing] that aspects of Mexican culture face.”

His ocean-waste exhibit at the Tianguis Turístico is anything but kitsch. It not only has a serious message, the integration of bits of plastic with more traditional beadwork perhaps affirms Wixárika respect for nature in the modern world.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico over 20 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.