I just got back from another trip to the United States!

We arrived in Texas on Easter Sunday, excited to enjoy some nice spring weather, as opposed to the usual oppressive summer heat or the winter cold (which, truthfully, is not that cold; I’m just very hard to please temperature-wise).

Much to my daughter’s disappointment, outside pools are still closed at this time of year. But we did have a very nice time being outside in general. We even went hiking at a state park!

And as always happens on these trips back home, friends and acquaintances asked me the question I’ve come to expect each time: how safe do I really feel in Mexico?

I wrote about safety precautions a few weeks ago already, but today I’d like to do a more nuanced dive into the particulars regarding the ways in which I feel safe (and sometimes not safe) in Mexico.

The easy answer is: yes, of course I feel safe in Mexico. If I didn’t, I wouldn’t be here.

Safety, however, depends on the particular topic at hand. So, with that in mind, I’d like to break down some of the particular circumstances that have me feeling confident and comfortable, or frozen and panicked.

First, the safe list: number one for me is the fact that most civilians in Mexico do not own guns. There are no “stand your ground” rules here, and assuming the perpetrator were caught, “I felt threatened and was defending my property” is not generally seen as a valid reason for shooting someone in the face.

While it’s possible to obtain hunting rifles, it’s certainly not as simple as walking into a gun store, and while many weapons are smuggled into Mexico from the U.S. by criminal groups, civilians are outright unable to get their hands on rapid-fire, military-grade weaponry legally. We have plenty of problems in Mexico, but mass shootings by mentally disturbed, disgruntled men isn’t one of them.

Curious children unwittingly shooting themselves or others while playing at home is also not an issue, thank goodness. While in Texas, I found myself the other evening suddenly in a state of panic, imagining just that scenario: I’d let my daughter go play at my sister’s neighbor’s house with her grandchildren, and it suddenly occurred to me that I should have asked beforehand if they kept guns in the home.

I ended up asking them to play in our backyard instead.

In addition to firearms not being available to the general law-abiding public, mentally ill loners seem to less easily fall through society’s cracks and into full-on psychosis here. Family is often close by, making it more unlikely that unhinged behavior will go unnoticed.

Secondly, the very fact that so many people are usually around — family and strangers alike — makes me feel generally safe.

Perhaps I’m being too optimistic, but having lots of people around me, even if I don’t know them, makes me feel like I’m part of a community, however small. The likelihood that all these people would let something bad happen to me or refuse to come to my rescue is low, though hopefully I’ll never have to test that theory.

I’ve also been happy to see that the behavior of strange men seems to have calmed down a bit since I first got here. Catcalls, getting grabbed, being creepily stared at in an obvious way — these seem (mostly) like things of the past. This could partially be because I’m spacey, not all that observant while in motion, and often have my earbuds in. It could be that everyone’s attention is on their cell phones instead of their surroundings these days.

It’s also possible, of course, that this is a result of me simply being older and looking less and less like the wild college students of Cancún on spring break. The fact that I’m now a señora is obvious, especially when I’ve got my kid in tow.

But I’m going to be optimistic, both about the prospect of men having become more respectful to strange women in public as well as my own aging looks.

Before moving on to the ways I don’t feel safe here, let’s talk about a midpoint that I can’t decide where to put: cars.

On the one hand, most people in Mexico are okay, if not daring, drivers. They have to be, because so many of the roads, signs, traffic signals and rules are so incredibly unstructured.

Drivers in my own city, desperate and grouchy from the traffic, routinely jump lights — “It’s about to turn green!” — and motorcycle riders seem to have bought motorcycles because it allows them to weave in and out of the traffic, not realizing they’re supposed to follow the same rules as larger vehicles.

Driving, riding in, and walking around cars is an adventure! And though I’ve had some close calls (knocking on wood and begging the gods not to punish me for my insolence in saying this), so far, I’ve been okay.

In what ways do I feel unsafe here? The common thread of all the things I’ve listed has to do with an absence of the rule of law, or at least imposable policies.

Let’s start with the most simple: in Mexico, “the customer is always right” holds little bearing; many places, in fact, seem to take the opposite view.

If your food or drink at a restaurant is terrible, it won’t be taken back because “you’ve already had some of it.” Getting your deposit back on a rental constitutes a miracle, and if you’re “accidentally” charged more for something when using your card, good luck getting it back.

Customers can make as loud a fuss as they can about something not being fair, but the burden of being fairly treated is entirely on them. In general, the absence of the rule of law in many areas in life makes it easy to get swindled, and hard to find any recourse.

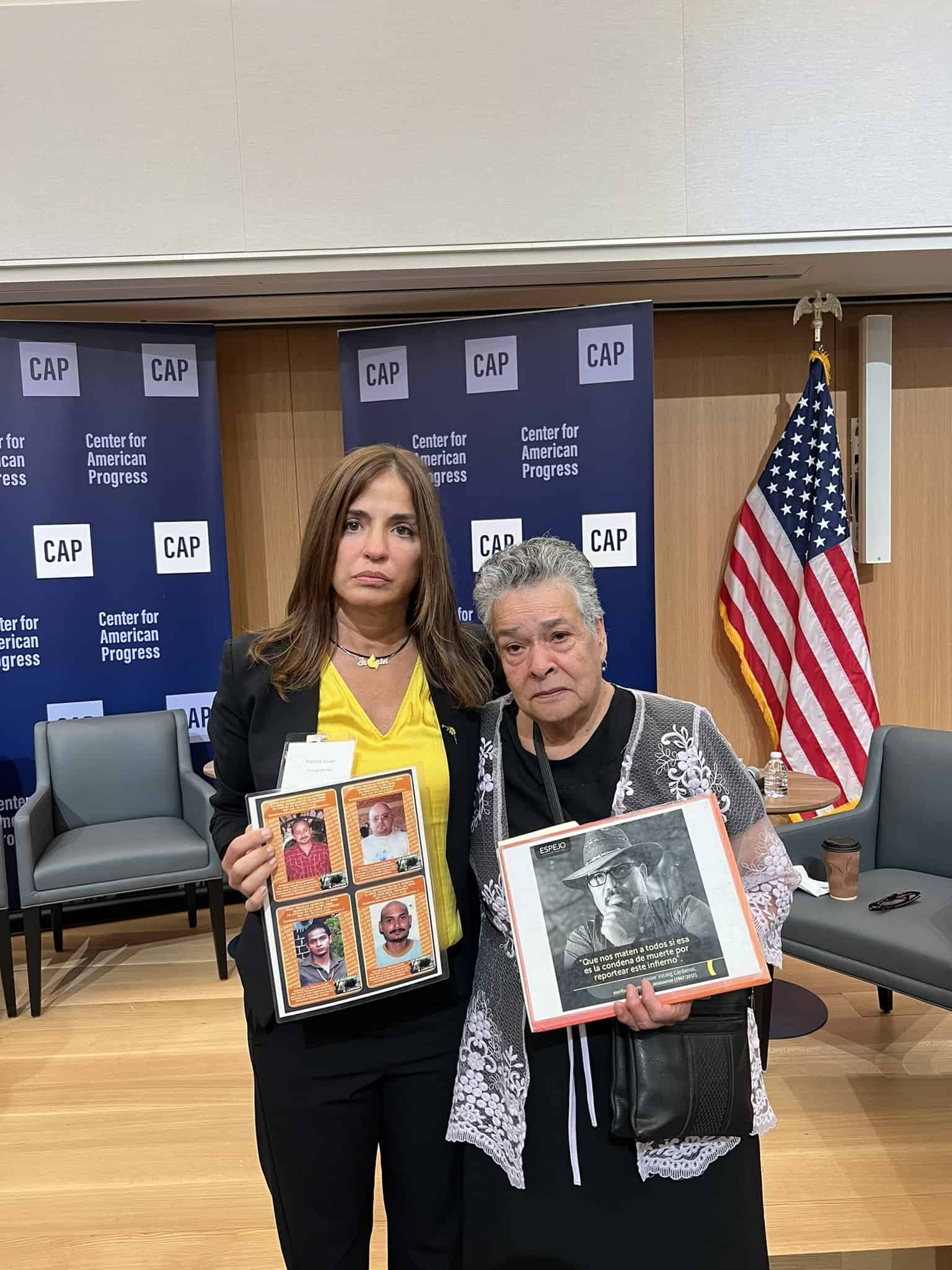

Writing, especially about Mexican politics, sometimes has me worried. For the most part, I assume that no one with much power here follows my little column in English. That said, I’ve received emails from readers before reminding me what an unsafe place this is for journalists, so when an idea for one of these controversial topics comes up, I do indeed think twice.

Nineteen-year-olds in uniforms with guns don’t necessarily make me feel safe, either, especially when reading about the abuses that are sometimes carried out at their hands. As much as AMLO likes to crow that “corruption is over,” in Mexico, that’s obviously not the case. Can a problem be solved if it’s not officially recognized by the authorities? Certainly not.

All in all, though, I feel as safe here as I do in my home country, and have accepted the tradeoffs. In the end, it’s all about the tradeoffs anyway, and I’ll take arguments at the bank over a crowd full of gun-carriers any day.

Sarah DeVries is a writer and translator based in Xalapa, Veracruz. She can be reached through her website, sarahedevries.substack.com.