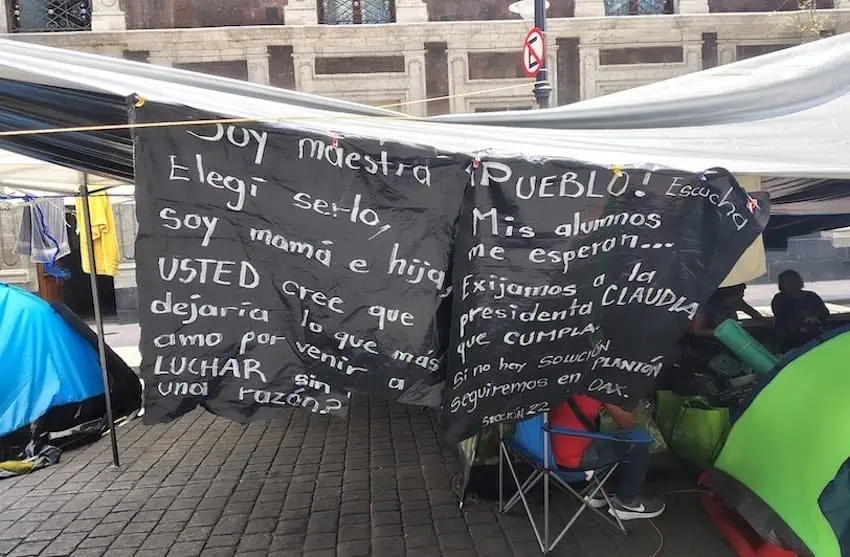

I’m a teacher, I chose to be one. I’m a mom and a daughter. Do you think I would leave what I love the most to come here to fight without a reason?

— Words on a placard affixed to a tarpaulin shelter at the CNTE teachers’ union protest camp in the historic center of Mexico City.

A tent city spreads across the Zócalo, the political and cultural heart of Mexico, and for more than three weeks in May and June the site of a massive teachers’ sit-in. Just off Mexico City’s main square a stench emanates from a row of portable toilets, an olfactory indication of just one of the hardships of extended protest.

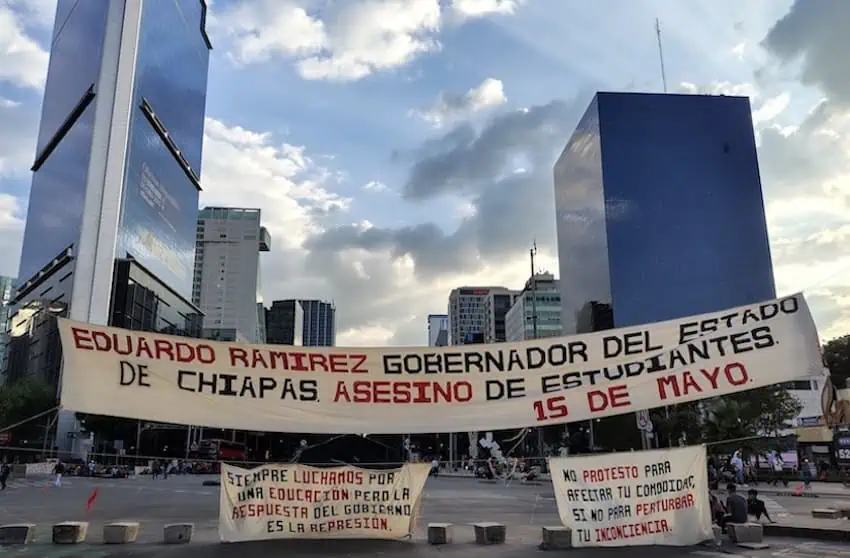

A group of young men partially block Paseo de la Reforma, Mexico City’s most famous boulevard, after having traveled almost 1,000 kilometers to the capital from the southern state of Chiapas, where their teachers’ college classmate was allegedly shot dead by state police.

Protest is a constant in Mexico City, the seat of the federal government and thus a focal point for angry, disgruntled and dissatisfied citizens from around the country. As the National Palace — the seat of executive power and now the president’s residence as well — is located opposite the Zócalo, the central square is the most popular place for demonstrations, and many protest marches end there after commencing in other central parts of the capital.

Every day, early in the morning, the Mexico City government publishes a roundup of the protests it knows will take place that day. It often lists 10 or more, but inevitably fails to mention them all.

That’s no surprise given that there are around 3,000 protests and road blockades annually in Mexico City, according to the city government, equating to an average of more than eight organized expressions of disgruntlement every single day of the year. Indeed, protests are as much a part of the fabric of life in the capital as taco stands and traffic-clogged streets.

Of course, marches and street blockades don’t make traffic flow any easier, but rather add to the frustrations of the millions of daily motorists and public transport users in the greater Mexico City area.

The snarling of traffic is just one of the ways that protests disrupt everyday life in the capital.

But given the frequency with which they occur, many residents reluctantly accept them — what else can they do? — as just another unavoidable tax on their time, and in some cases, on their income as well.

One day of protest in Mexico City

On the morning of Friday June 6, I caught the metro into the historic center of Mexico City and walked over to the Zócalo, where thousands of teachers from various states around Mexico had been sleeping in tents since May 15. That Friday turned out to be the final day of the CNTE teachers’ union sit-in, as the many maestros who descended on the central square in May to express their various grievances finally packed up their tents on Saturday June 7 and left, without their demands having been met, but vowing to continue to fight.

I spoke to a number of teachers, who enumerated their complaints, chief among which is their vehement discontent with the 2007 ISSSTE Law, which changed their pension system and will leave them — they say — considerably worse off in retirement. Their anger with President Claudia Sheinbaum — who during the 2024 presidential election campaign pledged on numerous occasions to repeal the 2007 ISSSTE Law — was palpable.

My visit to the teachers’ protest camp came the morning after a group of CNTE members broke into the Mexico City headquarters of the rival SNTE teachers’ union, set a fire alight in the building and carried out other acts of vandalism. During their lengthy stay in Mexico City, some CNTE-affiliated teachers used other violent tactics as they sought to get their message across. On May 21, for example, CNTE members allegedly attacked journalists who were trying to get into the National Palace to attend Sheinbaum’s morning press conference. Earlier this month, a group of teachers vandalized the headquarters of the federal Interior Ministry.

A faction of the CNTE from Guerrero is especially known for being radical. But on June 6, all the teachers I met from that state, and others, were polite, friendly, soft-spoken and even shy in some cases.

They spoke about their concerns that they won’t have enough money in their retirement. They told me about the difficulties they face now to support themselves and their families on monthly salaries of just 5,000 to 7,000 pesos (US $265-$370) after tax and other deductions (including union dues). They complained about their inability to access medical treatments at public healthcare facilities that their ISSSTE health insurance is supposed to cover. And they spoke about their overwhelming disappointment with Sheinbaum, who was supported by teachers — including CNTE members — in large numbers at last year’s presidential election.

All the teachers I spoke to were clear with their convictions and steadfastly committed to their collective cause.

But they did not deny that they had faced a range of challenges camping out in the Zócalo for three weeks during the annual rainy season: smelly and dirty toilets, no ready access to showering facilities, leaky tents, difficulty maintaining a healthy and balanced diet.

A couple from the Montaña region of Guerrero spoke about missing their young children, who they left with relatives to join the Mexico City protest.

Despite the hardships, the protesting CNTE teachers’ union members believe that their struggle is worth it, that they have to stand up for what they know is right. They believe — they know — they have to resist.

Of course, they are not alone in thinking that way — not in Mexico, not in the world. The recent protests against immigration raids in Los Angeles, and the “No Kings” protests on June 14, captured the zeitgeist of millions in the United States, providing one example of discontent about countless issues around the world.

In Mexico City’s central core, disaffection is on display in a variety of ways.

After I left the Zócalo on the first Friday in June, I walked to the Alameda Central, the large public park adjacent to the striking orange and yellow-domed Palace of Fine Arts. Lining the sidewalk at the park’s perimeter were female vendors, their various wares laid out next to or below posters and banners denouncing “economic violence” against women.

On boarding in front of the Benito Juárez Hemicycle — erected to protect the monument from vandalism by passing protesters — art calling for a “stop to the genocide” in Palestine and describing and depicting Donald Trump as a “colonialist, genocidal, coup-plotting pig” was on display. When I got to the intersection of avenues Júarez and Balderas, I saw a protest march approaching — judicial workers calling for a pay rise.

After passing countless protest messages scrawled on walls and the facades of buildings, I reached the intersection of Paseo de la Reforma and Insurgentes Avenue, Mexico City’s longest street. A huge banner accusing Chiapas Governor Eduardo Ramírez of being a “murderer of students” greeted me.

I approached a group of young men and asked them exactly what they were protesting. Their classmate, 22-year-old Jesús Alaín, who had almost completed his studies to become a primary school teacher, was shot dead by state police during a protest in Tuxtla Gutiérrez on May 15, they told me. Have any police officers been arrested? None, they said.

The young normalistas, as students that attend teacher training colleges called Escuelas Normales are known, had been camping at the Paseo de la Reforma-Insurgentes intersection for four days when I spoke to them. They said that authorities hadn’t made any serious attempt to dislodge them, but neither had they granted their requests to discuss the contested circumstances of the alleged murder in Tuxtla.

Unsurprisingly, the still-grieving young men want justice for their deceased classmate and friend, who will never get the opportunity to teach this generation, or any generation, of chiapaneco children as a fully qualified teacher.

In a country with sky-high levels of impunity, clamoring for justice is an unfortunate reality for millions of other Mexicans as well.

A short history of protest in Mexico City

Protest in its various forms — some of them extremely violent — dates back hundreds if not thousands of years. The Peasants’ Revolt in England in the late 14th century. The Evil May Day xenophobic riot in London in 1517. The Boston Tea Party in 1773.

In Mexico, there were Indigenous uprisings during the Spanish colonial period, a riot in Mexico City in 1692 due to food shortages and racial resentment, and a groundswell of discontent that led to a revolt against Spanish rule in the Mexican War of Independence.

In the early 20th century, there was significant unrest as Porfirio Díaz’s already long-running presidency continued. Examples of this included the Cananea strike in Sonora in 1906, in which Mexican copper miners protested against poor working conditions and salaries that were lower than those received by their American colleagues, and the Río Blanco textile workers’ strike in Veracruz the following year. There was significant violence linked to both strikes.

A few years later, Díaz’s fraudulent re-election in 1910 was the catalyst for the commencement of the Mexican Revolution.

In the second half of the 20th century, student protesters were violently repressed — and killed — by government forces controlled by the-then ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI.

On October 2, 1968, just 10 days before the start of the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City, the military opened fire on student protesters in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in the Tlatelolco neighborhood of the capital, killing hundreds.

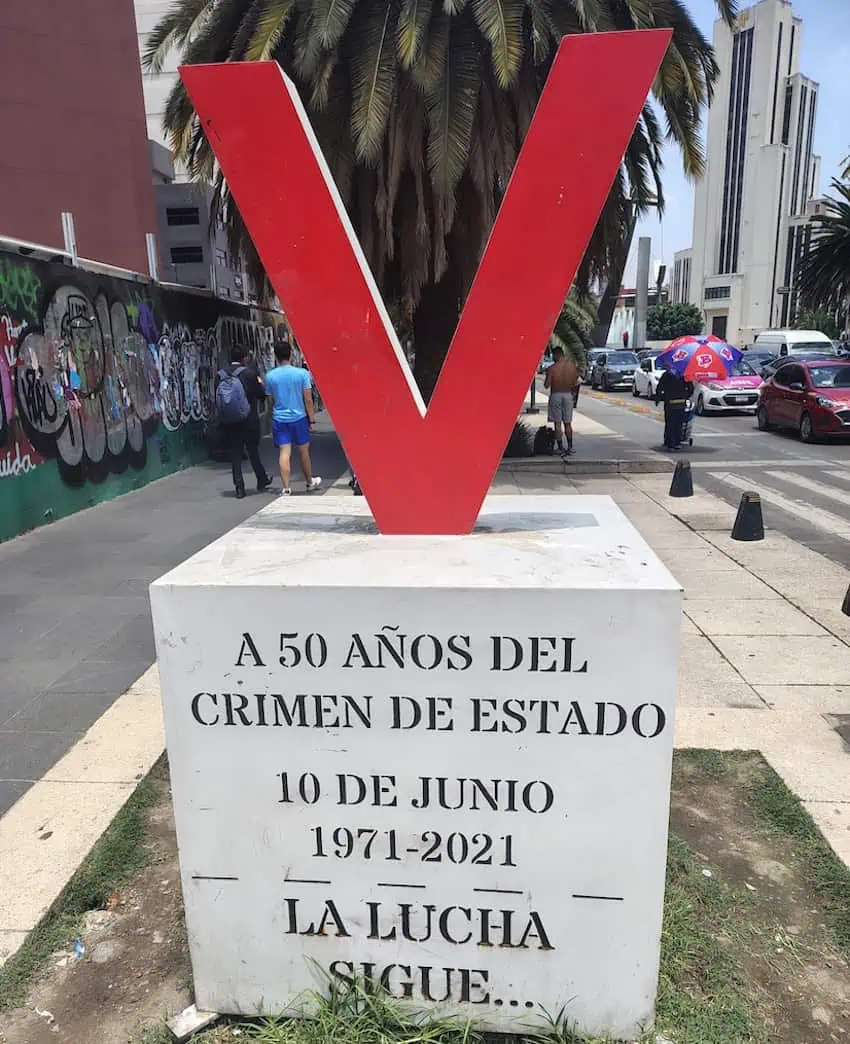

Less than three years later, another state-sponsored massacre of student demonstrators occurred in Mexico City. Known as “El Halconazo” (The Hawk Strike), as it was perpetrated by a government-trained paramilitary group called Los Halcones, the massacre claimed the lives of scores of students on June 10, 1971. It is briefly depicted in the award-winning 2018 film Roma.

Both the Tlatelolco massacre and El Halconazo (also known as the Corpus Christi massacre) are considered part of the Mexican Dirty War, an internal conflict from the 1960s to the 1980s in which successive PRI governments violently repressed left-wing student and guerrilla groups.

During this period, students and many other Mexicans participated in countless demonstrations against PRI authoritarianism. The students who participated in the 1968 protests had a range of demands, including the release of political prisoners and compensation for victims of police brutality and other state-sponsored repression. A march from Tlatelolco to the Zócalo commemorating those who lost their lives in 1968 takes place annually on Oct. 2.

In the first quarter of the 21st century, protest has remained a major facet of life in Mexico City.

Perhaps the most prominent protest movement of the first decade of the century was that led by Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) after his defeat at what he claimed was a fraudulent presidential election in 2006. AMLO led huge rallies in the Zócalo after the election won by Felipe Calderón, and set up a protest camp that extended kilometers down Paseo de la Reforma and remained in place for almost seven weeks.

He even had himself sworn in as Mexico’s “legitimate president” during a ceremony in the Zócalo in November 2006.

“The losing leftist candidate for president swore himself in on Monday as ‘the legitimate president of Mexico’ before a huge crowd of his avid fans, ignoring rulings by federal electoral authorities and the courts that he narrowly lost the election last July,” The New York Times reported at the time.

The following decade, massive protests broke out in Mexico City, and other parts of the country, after the disappearance of 43 students in Iguala, Guerrero, on Sept. 26, 2014.

Hundreds of thousands of people descended on the historic center of the capital during a series of protest marches in late 2014 that called for the ouster of then-president Enrique Peña Nieto. “Fue el estado” (It was the state) and “Vivos se los llevaron, vivos los queremos” (They were taken alive, we want them back alive) became national catchphrases. In the almost 11 years since the 43 young men disappeared, large numbers of Mexicans, including the parents of the abducted and presumably murdered students, have continued to protest, including on the 10th anniversary of the still unresolved crime.

Among the other large protests that have taken place in Mexico City in recent years are ones led by Mexico’s madres buscadoras, or searching mothers; marches every year on International Women’s Day; an anti-AMLO camp in the Zócalo; and demonstrations in defense of the National Electoral Institute.

While most protests are peaceful, some are marred by violence, usually perpetrated by a minority of protesters. Some protesters use very different techniques to attract attention to their cause, such as farmers from Veracruz who, in years gone by, bared (almost) all on numerous occasions while in Mexico City.

While Mexico City draws protesters from around the country, there are also a lot of smaller protests revolving around local issues in the capital, as is the case with residents of the Benito Juárez borough fighting to save a 115-year-old laurel tree known as “Laureano.”

All protests, whether big or small, are guaranteed by the Mexican Constitution, which states that “the right to peacefully associate or assemble for any licit purpose cannot be restricted.”

It also states that “only citizens of the Republic may take part in the political affairs of the country,” meaning that foreigners are officially barred from participating in political protests.

Of course many of the protests in Mexico City and elsewhere fail to achieve their aims. The CNTE teachers haven’t yet gotten what they want. No one has been convicted of involvement in the abduction and murder of the 43 Ayotzinapa students. Peña Nieto wasn’t forced out of office before the completion of his six-year term.

But even so, to protest is to do something; to not accept the status quo; to defy a feeling of helplessness; to demonstrate opposition; to resist.

In the words of Martin Luther King: “Every man of humane convictions must decide on the protest that best suits his convictions, but we must all protest.”

Permanent protest: Mexico City’s ‘anti-monuments’

Whether as sit-ins, hunger strikes, marches or the signing of petitions — to name just four — protest, as noted above, comes in various forms.

In Mexico City, there is a form of permanent, defiant and (almost) unmovable protest as well: the “anti-monument.”

There are a number of these antimonumentos — essentially sculptures of various kinds — in the capital, most prominently on Paseo de la Reforma.

An anti-monument calling for justice for the 43 abducted students. An anti-monument denouncing the 1971 “Halconazo.” An anti-monument inscribed with the message “No more femicides.” And various others.

The Mexico City anti-monuments “aren’t just a protest,” The Washington Post reported in 2024.

“Mexico’s leaders have long tried to control the historical narrative to legitimize their rule — from the Mexican-American War of the 1840s to the Revolution starting in 1910. Now, a movement of artists, grieving families and feminists is trying to wrest that narrative away.”

Disruptions and the financial cost of protests

At their heart, protests are about people — their grievances, their demands, their heartbreak, their quest for justice. While authorities are often the primary target of protesters’ frustration and anger, the residents of Mexico City frequently become collateral damage.

Motorists and public transit users, as mentioned above, are among the capital-dwellers who are affected the most.

“What is the most frustrating thing about the traffic,” a Televisa reporter recently asked a taxi driver in Mexico City, a metropolis ranked as the “most congested” city in the world on the 2025 Tom Tom traffic index.

“The marches, when they close [streets],” he responded, adding that traffic congestion at such times becomes “unbearable.”

With their camp at the intersection of Paseo de la Reforma and Avenida Insurgentes, the protesting normalistas from Chiapas prevented buses running on Line 1 of the Metrobús system from continuing on their normal route. Much to their annoyance, passengers traveling to the north or south of the city along Line 1 were forced to alight and walk a considerable distance to the next stop on the other side of the protest.

Back in the historic center of the capital, business owners incurred losses of 250 million pesos (US $13 million) due to lost sales during the three weeks of the CNTE teachers sit-in, according to an estimate from the Mexico City chapter of the National Chamber of Commerce, Services and Tourism (Canaco).

In a shopping plaza opposite the Zócalo that is filled with jewelry stores, several business owners and employees told me that their sales had declined while the teachers were camping out. They cited drop-offs in sales ranging between 50% and 80%.

The presence of the teachers’ camp is a “great annoyance,” one jewelry store owner told me, explaining that the area around the Zócalo is not such a pleasant place to visit or shop when tents fill the square as well as nearby streets and sidewalks. Tourists hoping to stroll around the large square while taking in nearby sites including the Metropolitan Cathedral and the National Palace were simply unable to do so in the second half of May and early June.

According to Canaco president Vicente Gutiérrez Camposeco, almost 17,000 businesses were affected by the CNTE protest. He explained that restaurants, hotels and stores were among those that suffered during the 23-day period the teachers remained in the Mexico City downtown.

While the CNTE union members no longer occupy the Zócalo, protests in the central square, and indeed all over this sprawling capital city, will in all likelihood remain an ongoing recurrence as long as humans continue to live here.

Being held up by one — as will inevitably happen if you spend any length of time in the capital — is a Mexico City experience every bit as authentic as chowing down on a plate of tacos al pastor, floating through the canals of Xochimilco on a trajinera or watching the lucha libre with thousands of other michelada-guzzling fans.

Text and photographs by Mexico News Daily chief staff writer Peter Davies (peter.davies@mexiconewsdaily.com)