The Mexican Army killed Nemesio “El Mencho” Rubén Oseguera Cervantes — the founder and top leader of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG) — on Sunday morning in the municipality of Tapalpa, Jalisco, roughly 90 kilometers south of Guadalajara.

His death triggered a wave of cartel reprisals across at least half of Mexico’s 32 states, raising urgent security questions just weeks before the 2026 FIFA World Cup playoffs are set to begin in Guadalajara.

Here is what we know so far.

The operation

— The Ministry of Defense confirmed that federal forces attempted to arrest Oseguera Cervantes in Tapalpa during a Sunday morning operation. Residents in the area reported overflights and military convoys prior to the raid.

— During the operation, Mexican military forces came under fire and were forced to defend themselves, the Defense Ministry said. Four CJNG operatives were killed at the scene. Three others, including El Mencho, were critically wounded and airlifted to Mexico City, where all three died en route.

— Twenty-five National Guard officers, a state police officer, a security guard and a woman were killed in attacks in Jalisco. According to the security ministry, 34 criminals were killed in incidents following the operation.

— Three Mexican soldiers were also wounded in the firefight and transferred to Mexico City for medical treatment.

— U.S. authorities contributed intelligence used to carry out the operation, the Defense Ministry said.

Read more about the operation here:

How Mexico found ‘El Mencho,’ according to the Army

Who was ‘El Mencho’?

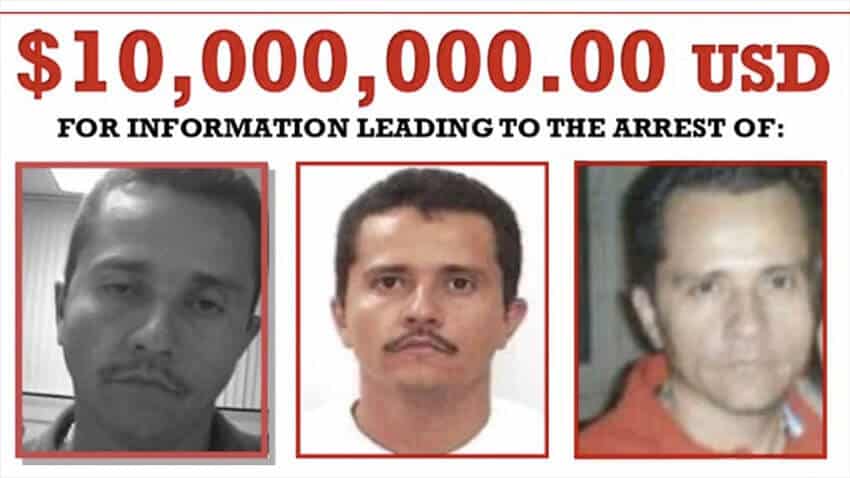

— Oseguera Cervantes led the CJNG, widely considered one of the most powerful and violent criminal organizations in Mexico, with a strong presence in Jalisco, Colima, Guanajuato, Michoacán and other states.

— He played a central role in the trafficking of cocaine, methamphetamine, and, more recently, fentanyl into the United States. The U.S. Department of Justice had issued federal charges against him and offered a multimillion-dollar reward for information leading to his capture.

— Security analysts warn that his death could trigger internal reshuffling and succession disputes within the CJNG, likely leading to increased violence across territories the cartel controls.

The cartel’s response

— Within hours of the operation, CJNG members erected between 80 and 250 narco-blockades and set vehicles, buses and businesses ablaze in 20 states.

— In Puerto Vallarta, residents reported the city under siege — the sound of gunshots and thick columns of black smoke rising over the city as more than 10 vehicles and several businesses were set on fire in various points. Prison breaks were also reported in the city.

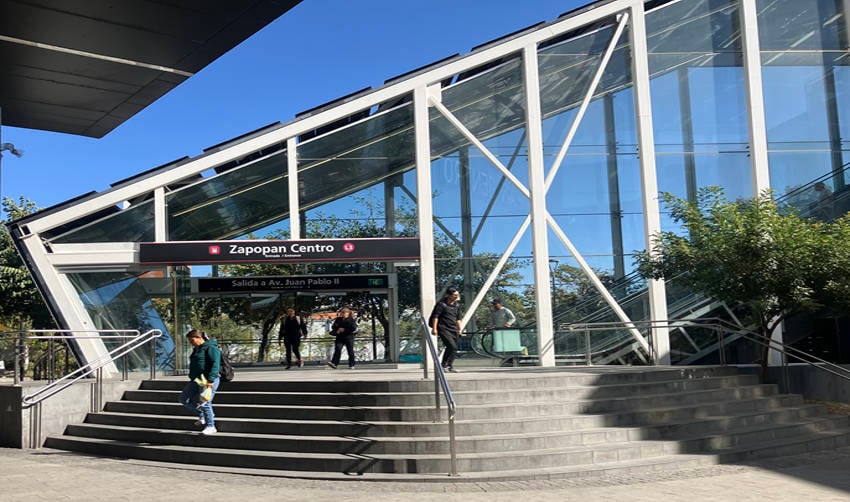

— In Guadalajara, roadblocks were reported across the metropolitan area. Vehicles and public buses were burned. Pharmacies and convenience stores were set on fire across Mexico.

— In Michoacán, Governor Alfredo Bedolla reported that 13 municipalities were experiencing unrest. Further disturbances were reported in Veracruz, Colima, Aguascalientes and Guerrero.

— Guanajuato later reported that blockades in that state had been contained and no longer posed a risk to residents.

Government response

— Jalisco Governor Pablo Lemus declared a statewide “Code Red,” suspending public transportation, in-person classes and mass events for the remainder of Sunday and through Monday.

— The governor of neighboring Nayarit, Miguel Ángel Navarro, issued a similar warning, calling on residents to shelter in their homes.

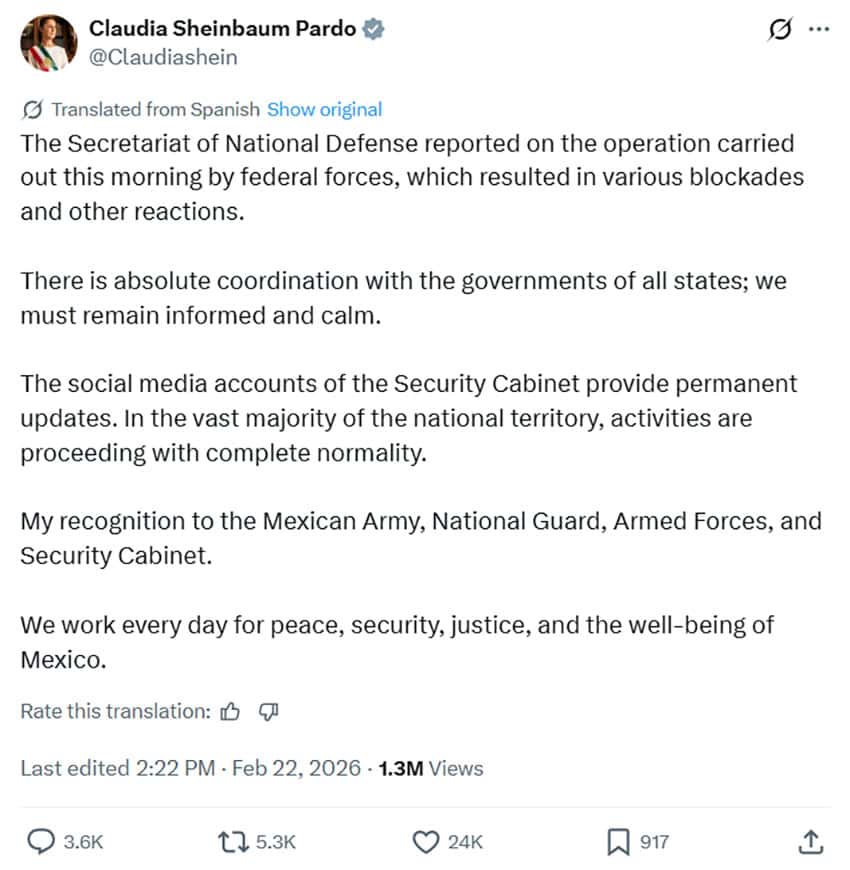

— President Claudia Sheinbaum urged Mexicans to remain calm in a Sunday afternoon post on social media, saying there was “complete coordination” with all state governments and that activities were proceeding normally in most of the country.

— Mexico’s security minister said “the majority” of the blockades set up by the CJNG were removed on Sunday and that there were zero blockades as of Monday.

— Authorities arrested 70 people across seven states for allegedly committing crimes motivated by the operation against Oseguera.

Travel alerts and transport disruptions

— The U.S. Embassy issued a shelter-in-place order for American citizens in Jalisco — including Guadalajara, Puerto Vallarta and Chapala — as well as in parts of Tamaulipas, Michoacán, Guerrero and Nuevo León, citing “ongoing security operations and related road blockages and criminal activity.”

State, foreign governments issue shelter-in-place warnings as narco-blockades spread after cartel leader’s death

— Canada issued a shelter-in-place order specifically for Puerto Vallarta and advised all citizens in Jalisco to keep a low profile and follow local authorities.

— The United Kingdom updated its travel advice to warn against all but essential travel to parts of southern and northern Jalisco. Australia and India also issued security alerts to their nationals in Mexico.

— The Pacific Airport Group (GAP) said Guadalajara International Airport was operating normally under the protection of the National Guard and the Army. The airport attributed videos of panicked passengers circulating on social media to “hysteria among passengers” rather than an actual security incident.

— Air Canada temporarily suspended operations at Puerto Vallarta’s airport. Some flights from Manzanillo, in the neighboring Colima state, were also canceled.

— Bus services were suspended across multiple areas of the country, including routes between Mexico City and San Miguel de Allende. Hotels in Puerto Vallarta advised guests to remain indoors.

Will FIFA cancel the 2026 World Cup in Mexico?

— Guadalajara is a host city for the 2026 FIFA World Cup. The Estadio Akron is scheduled to host four group stage matches, including Mexico vs. South Korea on June 18 and Uruguay vs. Spain on June 26.

— More immediately, the Estadio Akron is set to host a World Cup playoff tournament on March 26-28 — just over a month away — featuring New Caledonia, Jamaica and DR Congo competing for a spot at the finals. Monterrey will host the other side of the bracket, with Iraq, Bolivia and Suriname also vying for a place.

— The violence in Guadalajara raises serious security concerns about Mexico’s readiness to host tens of thousands of international visitors, fans and officials.

— Lemus told The New York Times’ The Athletic on Sunday that his office had not received any communications from FIFA that should cause concern. “We are focused on controlling the situation,” a spokesman said.

— Lemus had previously outlined plans for the World Cup that include a state-of-the-art video surveillance system throughout Guadalajara, along with active patrols by the National Guard and Mexican Army across the metropolitan area during the tournament.

— The inaugural match of the 2026 World Cup is scheduled for Estadio Azteca in Mexico City, between hosts Mexico and South Africa.

— FIFA had not publicly commented on the unrest or its potential impact on World Cup preparations as of publication.

Mexico News Daily