The World Bank has lowered its economic growth forecasts for Mexico for this year and the next two, citing uncertainty for investors among the reasons for its more pessimistic outlook.

The Washington D.C.-based financial institution is now predicting that the Mexican economy will grow 1.7% this year, 0.6 percentage points lower than its 2.3% forecast in June.

The World Bank anticipates GDP in Mexico will increase 1.5% in 2025, 0.6 points lower than its previous 2.1% forecast.

It also cut its forecast for 2026, lowering it to 1.6% from 2%.

The updated growth forecasts are included in the World Bank’s latest Latin America and Caribbean report, which was published on Wednesday.

If the projections come true, economic growth in Mexico will slow for a third consecutive year in 2024 and a fourth consecutive year in 2025.

The Mexican economy grew 6% in 2021 as it bounced back from a sharp pandemic-induced contraction in 2020. Growth moderated to 3.7% in 2022 before declining to 3.2% last year.

In the first half of 2024, annual growth was just 1.5%.

Why did the World Bank cut its growth forecasts for Mexico?

William Maloney, World Bank Chief Economist for Latin America and the Caribbean, told a virtual press conference that high interest rates in Mexico, a weaker Mexican peso and uncertainty for investors were all factors in the lower growth forecasts.

The Bank of Mexico has cut its benchmark interest rate on three occasions this year, but it remains high at 10.50%.

The Mexican peso has weakened considerably since the June 2 elections, in large part due to concerns over the federal government’s judicial reform, which was signed into law by former president Andrés Manuel López Obrador two weeks before he left office.

The Wall Street Journal reported last month that foreign companies were holding back approximately US $35 billion in investment in Mexico due to uncertainty related to the judicial reform and the upcoming United States election. There are concerns that respect for the rule of law in Mexico will suffer as the result of the direct election of judges by citizens.

Maloney on Tuesday stressed the need for Mexico to create stability for investors by respecting the “rules of the game” for investment in the country.

He acknowledged that Mexico has made progress in combating poverty — including by increasing the minimum wage — but highlighted that more needs to be done. Maloney also said that advances in infrastructure (including water and energy infrastructure), innovation and education are crucial to Mexico’s future success.

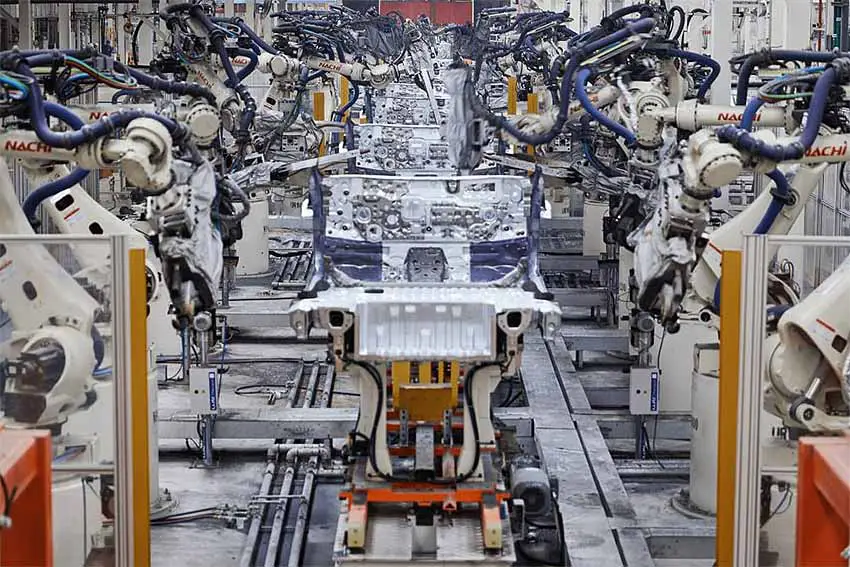

In addition, the World Bank economist said that Mexico is well positioned to benefit from nearshoring, but added that the country needs to do more to attract foreign investment.

What does the World Bank report say about Mexico?

Entitled “Taxing Wealth for Equity and Growth,” the World Bank’s latest Latin America and Caribbean report also includes updated growth forecasts for other countries in the region, and the region as a whole.

The World Bank is forecasting that the regional economy will grow 1.9% this year and 2.6% in 2025.

Early in the 98-page report, the World Bank acknowledges that Mexico has “increased its level of private investment, by taking advantage of opportunities for nearshoring and friendshoring, and public investment, especially on infrastructure projects.”

Later in the report, the bank says that “Mexico’s policy of increasing the minimum wage from the previously low level” — it almost tripled during López Obrador’s presidency — “appears to have had some positive effects on earnings, and reducing poverty.”

“Yet, the economic literature and the region’s experience clearly suggests that there are limits to this strategy. The initial positive effects in Mexico may be related to the fact that minimum wages started off at very low levels relative to median or average wages, and further increases may have important employment trade-offs to consider,” it adds.

Toward the end of the report, the World Bank highlights that Mexico has the second highest number of billionaires among Latin America countries after Brazil. Mexico’s richest person is Carlos Slim, who, according to Forbes, is the 20th wealthiest person in the world.

“While rich,” Latin America’s billionaires are “modest” by global standards, according to the World Bank, which highlights that “the combined wealth of the top ten billionaires worldwide — nine of whom reside in the United States — totals an astounding [US] $1.7 trillion, nearly equal to Brazil’s GDP, and almost triple that of Argentina.”

With reports from El Economista, EFE, El Universal and El Financiero